a few notes on art and the transcendent

just because.

This is Life is a Sacred Text, an expansive, loving, everybody-celebrating, nobody-diminished, justice-centered voyage into one of the world’s most ancient and holy books. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here.🌱

As always, a reminder that subscriptions get you more goodies for your bang (and those goodies will get even goodier in the year to come), they support the labor that goes into this work, and that subscriptions (individual, group and gift! just check the tab at the top) are 20% off through the end of December!

Also remember that when you tell friends about this project, you can get freebees on subscription months:

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday Haus O’ Study and paying isn’t for you right now, hit me up at LifeIsASacredText@gmail.com and we’ll hook you up.

(If you can help subsidize those subscriptions, please do so here!)

.OK. On to our conversation for the day.

There's an old story about Michelangelo—he was making a tremendous racket in his studio in the middle of one night, so a disgruntled neighbor came rushing in, asking what on Earth he might be doing a such an untimely hour.

As the legend goes, the sculptor looked up from the gigantic block of marble he was straddling, chisel in hand.

"There's an angel trapped in here," he said, "and I'm trying to get him out."

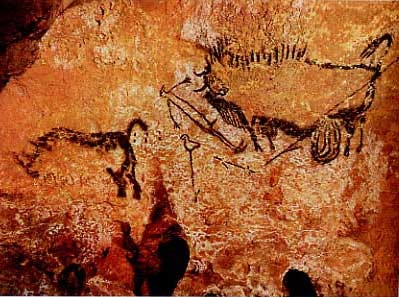

Art and religion have a long and intimate history that may well trace to the origins of both; scholars speculate on whether or not cave paintings may have served a shamanic purpose.

The Mesopotamian architectural masterpiece, the ziggurat, was, quite literally, considered a "stairway to heaven."

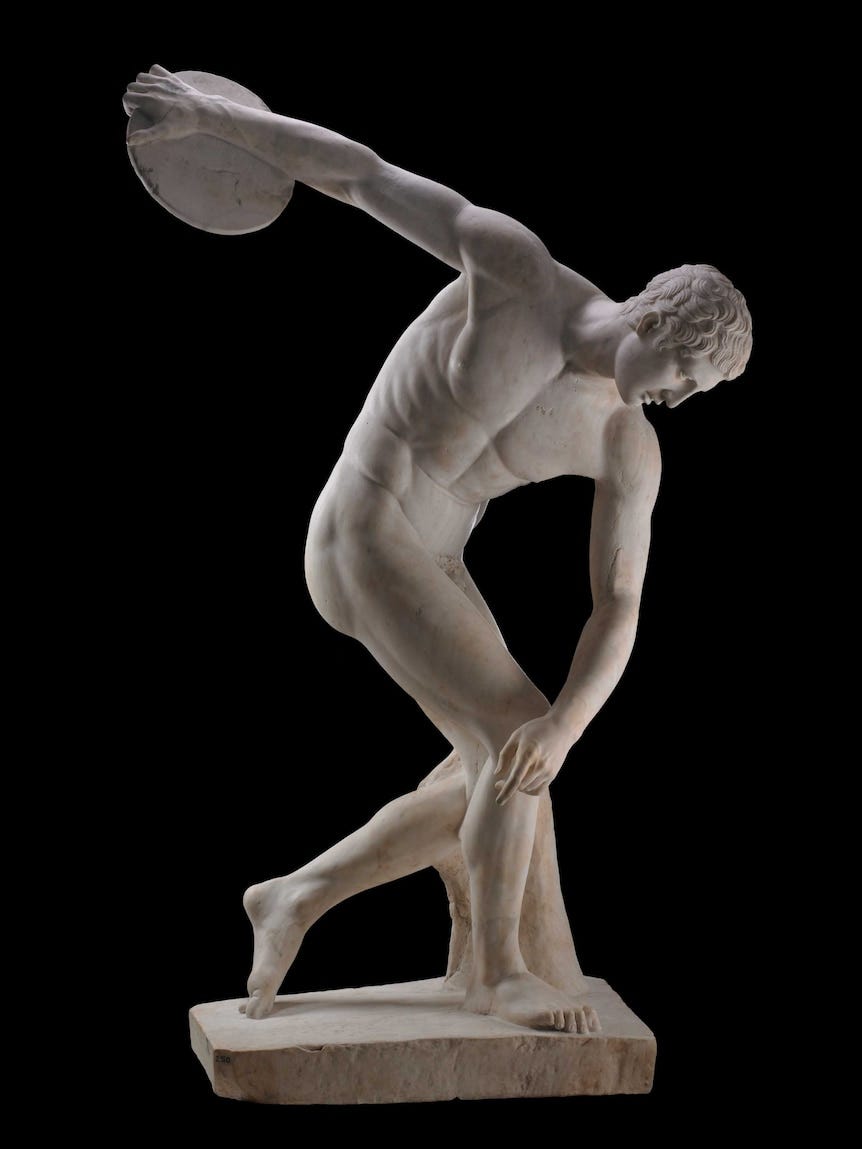

The Ancient Greek rendering of ideal beauty was steeped in the philosophical urge to render the divine archetype of Beauty itself.

Visual art and architecture—so too, with music, dance and writing—has long served as a conduit, a mirror, an explication and an elaboration of theology and spiritual beliefs. The magnetic pull between the two disciplines does, in many ways, show us much about the underpinnings of both.

Like art, religion gets at who we are, and what we want. It gives voice to our anxieties, preoccupations, and, perhaps most potent of all: the questions we cannot answer any other way.

Like religion, art attempts to express the inexpressible—to get at the mysteries residing in the corners and the cracks of our lives.

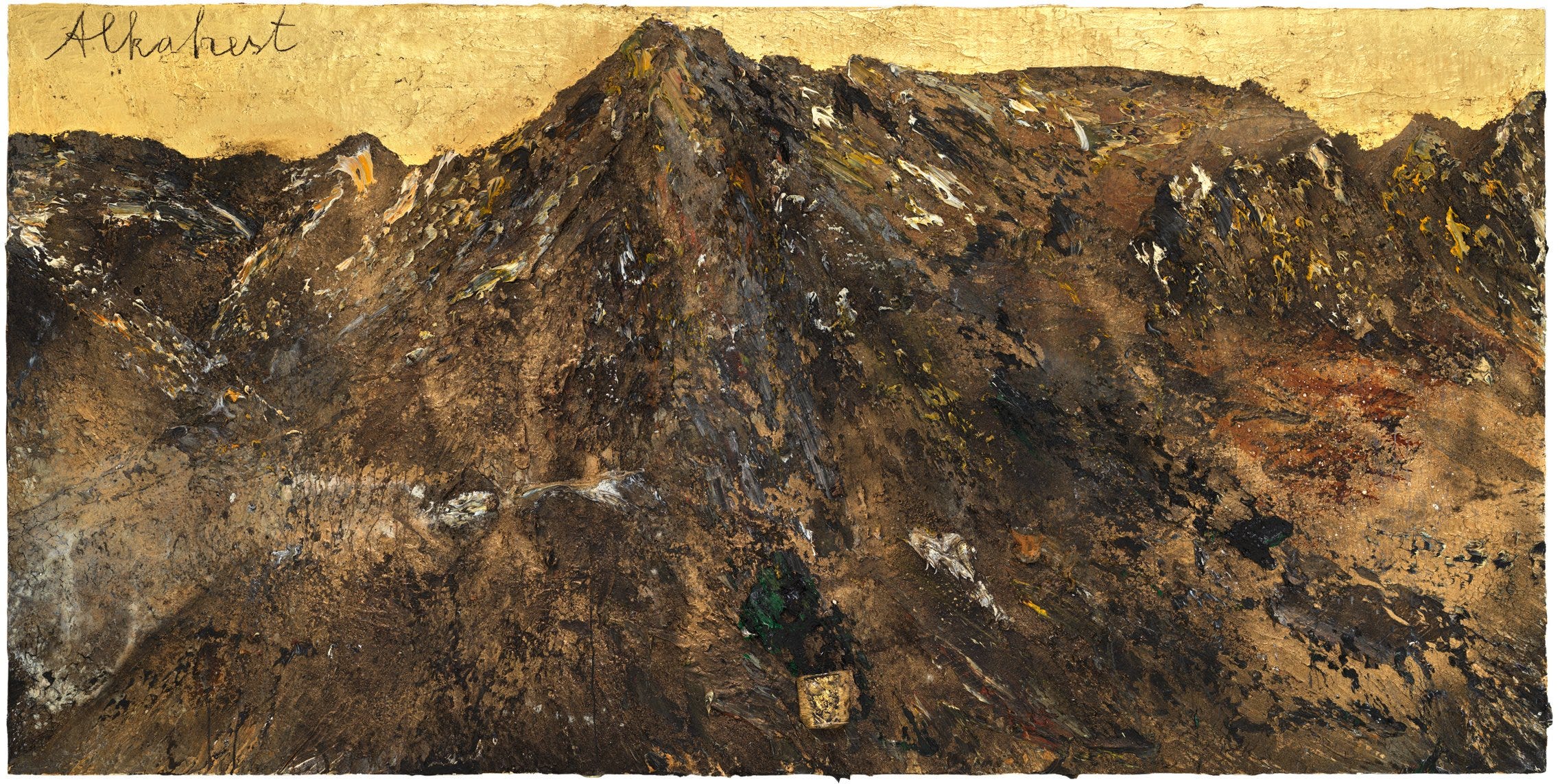

The German contemporary artist Anselm Kiefer once said,

“Angels take many forms. Satan was an angel. We are not capable of imagining God in a pure state. We need symbols that are less pure, that include human elements….

The light we see today was emitted millions, billions of years ago and of course their source was constantly changing, moving, and dying. These lights we see, this heaven has nothing to do with our current reality. …we have to make sense of the world…

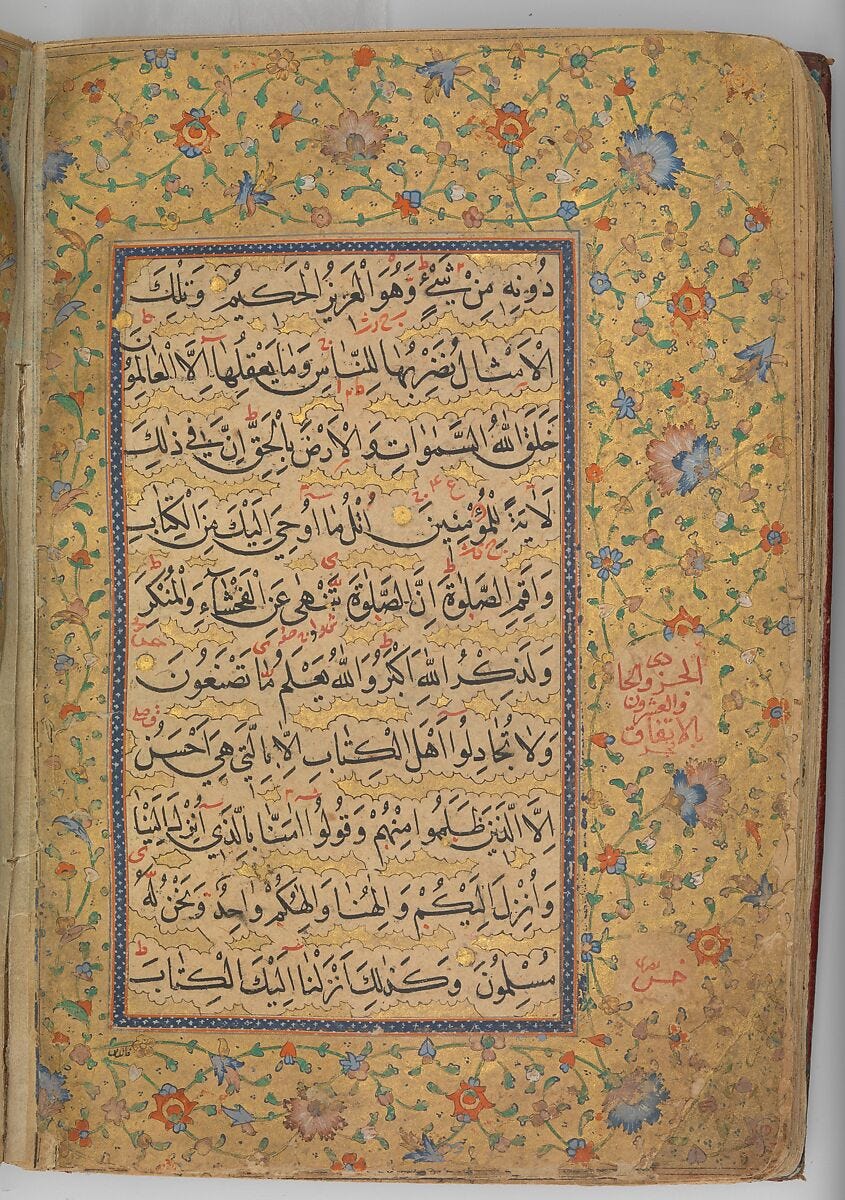

Much (most?) of the most important artifacts of visual culture from around the world have been created in the service of divinity: Persian illuminated manuscripts of the Qur'an, lost-wax sculptures of the Hindu pantheon, Yoruba masks created for ritual connection, Mayan temple pyramids… the list goes on.

While the racism and colonialism pervading our cultural imagination still often attempts to distinguish between ritual objects and "fine art," it's not insignificant that the building-blocks of the Western art canon, Christian iconography, operate on many of the same principles as other religious art throughout the world.

Portrayals of saints and the sanctified are traditionally viewed as manifestations of the divine in the human realm, the eternal in the temporal—as a mirror of the Christian trope of divine events entering our mundane everyday reality.

In the medieval era, Christian art was used to help teach a largely illiterate population the stories of both Hebrew Bible and New Testament, and the 1563 the Council of Trent stated explicitly that art was not "for its own sake" but rather tool to help both painter and viewer access the divine meaning behind it.

It was the Renaissance's fascination with humanity in general and the Protestant Reformation's rejection of the Catholic Church (in favor of a more individually-focused religious experience) that enabled an independent artistic tradition to emerge.

As the Church began to lose some of its massive political power in the 16th and 17th centuries, art began to be created for its own sake.

Nonetheless, the themes, stories, and ideas of the religious world have, through the last 400 years—including the secularization of government, the philosophical “death of God” and both Modernist and Postmodernist critiques—continued to capture the artistic imagination.

The imagery uses the artist

Still today, many artists regard themselves as are mere vehicles for something quite ineffable.

As the vocalist Rachel Bagby put it,

"All I need to do is open my mouth and the sound is there. It's as though the music pre-exists before mouth and teeth and tongue and larynx, and there's this partnership with the wind of life blowing through [me, as the] instrument."

Or, as renowned poet and author Marge Piercy once told me,

"there are times when one experiences a certain flow of imagery. And it simply picks you up and uses you."

Renowned video artist Bill Viola once said something similar:

“The basis of the artistic act is giving oneself to something. It’s a kind of surrender.”

Or as poet Joy Harjo once said:

“I agree with Gide that most of what is created is beyond us, is from that source of utter creation, the Creator, or God. We are technicians here on Earth, but also co-creators. I’m still amazed. And I still say, after writing poetry for all this time, and now music, that ultimately humans have a small hand in it. We serve it. We have to put ourselves in the way of it, and get out of the way of ourselves. And we have to hone our craft so that the form in which we hold our poems, our songs in attracts the best.”

Which isn’t to say that it happens, for most artists, easily or automagically. For most creatives, keeping the muscles of the imagination strong requires rigorous discipline, just as staying in marathon-runner shape demands a regular date with the gym shoes. As Sculptor Sandy Shannonhouse put it,

“art doesn’t just grow. If you’re making things, if you’re making sculpture or computer art, or whatever, you have to do it and go through it for there to be growth.. [for,] if you’re making something that comes out of your being, you’re peeling away layers [to] get to something that’s uniquely yours.”

She continued,

“the daily practice of making art is so spiritual, and that carries into the rest of my life,”

just as someone who sits daily Buddhist zazen or davens daily in Jewish minyan cannot help but be altered by a routine return to a place of holiness—day after day after day. Even if today’s meditation or prayer practice didn’t feel like much, even if it was flighty, distracted. It still did something. Whether or not its impact is manifest right away, whether or not it’s clear that anything happened. Just like every jog strengthens the body, whether or not one gets a runner’s high that day.

Everyplace.

Natalie Goldberg wrote in her long-celebrated Writing Down the Bones, "About three years ago [Katagiri Roshi] said to me,

'Why do you come to sit meditation? Why don't you make writing your practice? If you go deep enough in writing, it will take you everyplace.'"

What does that look like? Poet and theologian Christine Valters Paintner articulates beautifully one of the faces of creative work as a spiritual practice:

the creative process - creating for the joy of doing rather than for the product, is to explore creativity in a deeply intimate way and honors the process itself rather than focusing on the finished work. To be truly creative, one must move between states of openness to new associations of ideas and states of focused explorations of these associations. The meditative mind is open to flashes of insight because it is open rather than constricted. Similarly, prayer is an act focused more on the process itself rather than the outcome. We engage in a discipline within which we cultivate an attitude of openness towards surprise and serendipity, while we wait with patience and humility.

In fact, the moderinst Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky wrote On the Spiritual in Art in 1910 (between revolutions!) that making art can be a way out—an access point, a ladder, when things feel hardest and most hopeless. A way of accessing the transcendent when we can’t seem to find it any other way:

When religion, science and morality are shaken … and when the outer supports threaten to fall, [a person] turns his gaze from externals in on to [them]self. Literature, music and art are the first and most sensitive spheres in which this spiritual revolution makes itself felt. They reflect the dark picture of the present time and show the importance of what at first was only a little point of light… [and] turn away from the soulless life of the present towards those substances and ideas which give free scope to the non-material strivings of the soul.

And, if you go down deep enough, that everyplace articulated by Katagiri Roshi can be communicated to the people who see, hear, watch, or read.

Most people can recount an experience hearing a musician whose passion was infectious, or seeing a work of art that allowed you to almost feel the artist’s emotions.

As Bagby put it:

“There’s a place where the viewer/listener/participant dichotomy just kind of falls away.” Her work, she says, is “not an invitation for [the audience] to partake of my spiritual life, but rather there is the spiritual life that we get to celebrate together. It’s almost as though I get to help throw the party. I get to help decorate the house.”

In this way, even the audience becomes the artist; the demarcations between self and other become blurry. Many spiritual practices talk about the quelling of the ego—and here, willing members of an audience can become subsumed by the force that drives the work.

Art and spirituality aren’t the same thing, but they’re certainly vehicles for each other—art can be used to access one’s deepest spiritual beliefs, just as religion can be a means of connecting with the stuff of one’s creative self.

You don’t have to be a career artist in order to hear it, either; anything from writing in a journal to drumming in a living room band to shaking your booty at the dance club counts.

What’s important, most of all, is the process of tuning into the still small voice within and seeing what comes out.

There is a long tradition of mystics—from the Islamic scholar and Sufi poet Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī to the composer-nun Hildegard Von Bingen to poet and printmaker William Blake, before that and beyond—who use art as a means both of expressing divine visions and of understanding what the compulsion to create really means.

“What happens before birth and resumes after death - this is more real than the brief spark of life. Out lives just carry the physical burden of carrying energy forward. We put on suits of meat as training, as a challenge. We all know this is temporary.”

― Tanya Tagaq, Split Tooth

Religion is, in many ways, all about making stuff.

Form from void, humans from dust, meaning and order from the chaos of human angst; the ability to create, to shape something comprehensible from the intangible depths has long been a power ascribed to the divine realm.

(In many other ways it’s about honoring that which has been created, the Creator, or getting in touch with our interconnectedness with the rest of creation—and our obligations that flow from that.)

So what, then, of each hungry soul who fills a canvas with light or a blank page with words?

This tiny replication of creatio ex nihilo is a potent one, and while most artists are not—despite their own illusions or even a good write-up in the New York Times—seraphs sent from above on divine emissary, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t

Rabbi Adina Allen, author of the forthcoming The Place of All Possibility: Cultivating Creativity Through Ancient Jewish Wisdom, and founder of the Jewish Studio Project, writes,

Creativity as a spiritual practice is a way for us to partner with God and to develop the character traits that allow us to stay in ongoing co-creative partnership. What this relationship requires of us is an openness to the creative process: a willingness to venture into the unknown, the ability to be present in the moment, an openness to our intuition and allowing ourselves to follow where it leads us, and a deep humility in knowing that nothing we bring into the world is ours alone.

We can be willing to spend time being creators, not destroyers. Opening the places within that are yet unknown to us and lifting them up and out—a tapping in, a connection, an offering.

(“the hidden things are for God, the revealed things are for us,” Deuteronomy 29:28)

We can all create. All of us. We don’t have to be “good”—making art, doing improv, sketching, journaling, crafting, dancing, singing, painting, sculpting with air-dry clay, any of it, all of it—it is ours, and it can be a spiritual practice. Another way to reach out to, and to connect with, the great transcendent beyond, the Big Bigness that lives within and beyond ourselves.

You, too.

As we are here on the cusp of a new Gregorian year, I am here with an invitation:

Give yourself permission.

“In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.”1

In comparison, maybe a haiku or a charcoal drawing doesn’t seem so hard to knock off, after all?

If you’d like some prompts for conversation, here are a few:

What do you think of the notion of art as a means to tap into the divine?

How does your spiritual/religious life influence the way you think about creative work? Creative thinking?

How does your creative work influence the way you think, spiritually?

What is your creative process?

If you’re not someone with a regular creative practice, what keeps you from this?

Tell me about "the muse" and "the deity".

If you have an organized religious practice, where does the structure of your actions fit in?

What are your thoughts about the role of discipline in religious practice and creative work?

Do you think art and religion have similar goals? What's similar, what's different?

What's the relationship between artist and audience re: conveying the transcendent?

Is it possible for the audience to partake of the artist's spiritual life? If so, how?

🌱 Like this? Get more:

Life is a Sacred Text is a reader-supported publication.

To get new posts and to support the labor that enables this project to exist, become a free or paid subscriber. Get long substantial essays like this for free, and paid subscribers get even more text and provocation, on the reg.

Life is a Sacred Text is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

And right now it’s a perfect time to get Life is a Sacred Text as a gift for someone who’d love nourishment and provocation for brain, heart and soul (and that someone can be you!)

The more friends you share this with the more months of free subscription you get!!!

And please know that if you want into the Thursday conversations but paying isn’t on the menu for you right now, we’ve got you. Just email lifeisasacredtext@gmail.com for a hookup.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so here.

Please share this post:

💖 Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💖

Genesis 1:1, natch ↩