on betrothals and beyond

Jewish weddings and ritual innovation

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

Today we're going to talk about a Jewish wedding ritual thing!

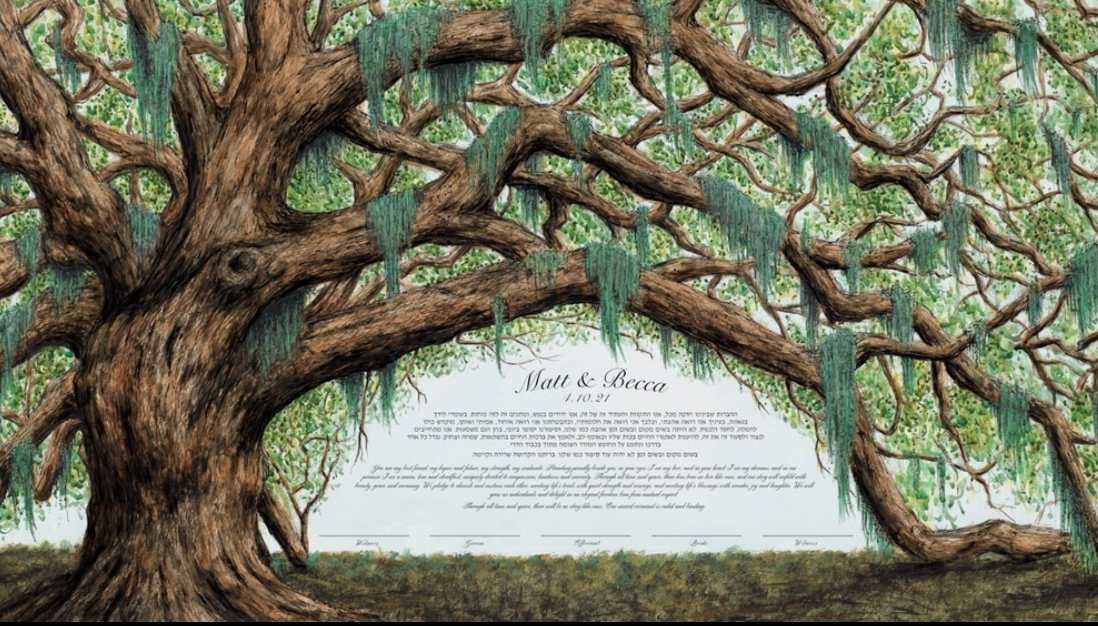

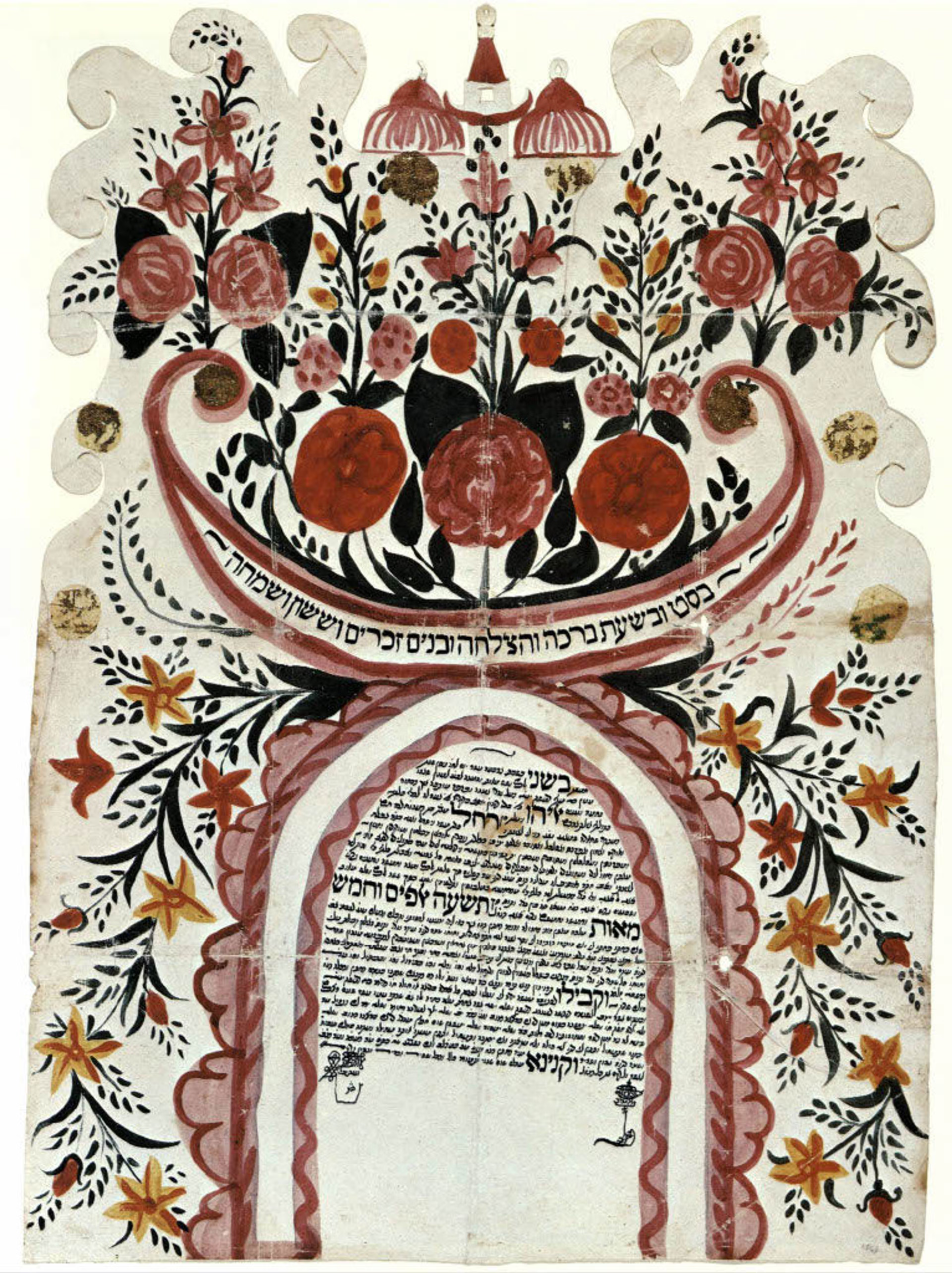

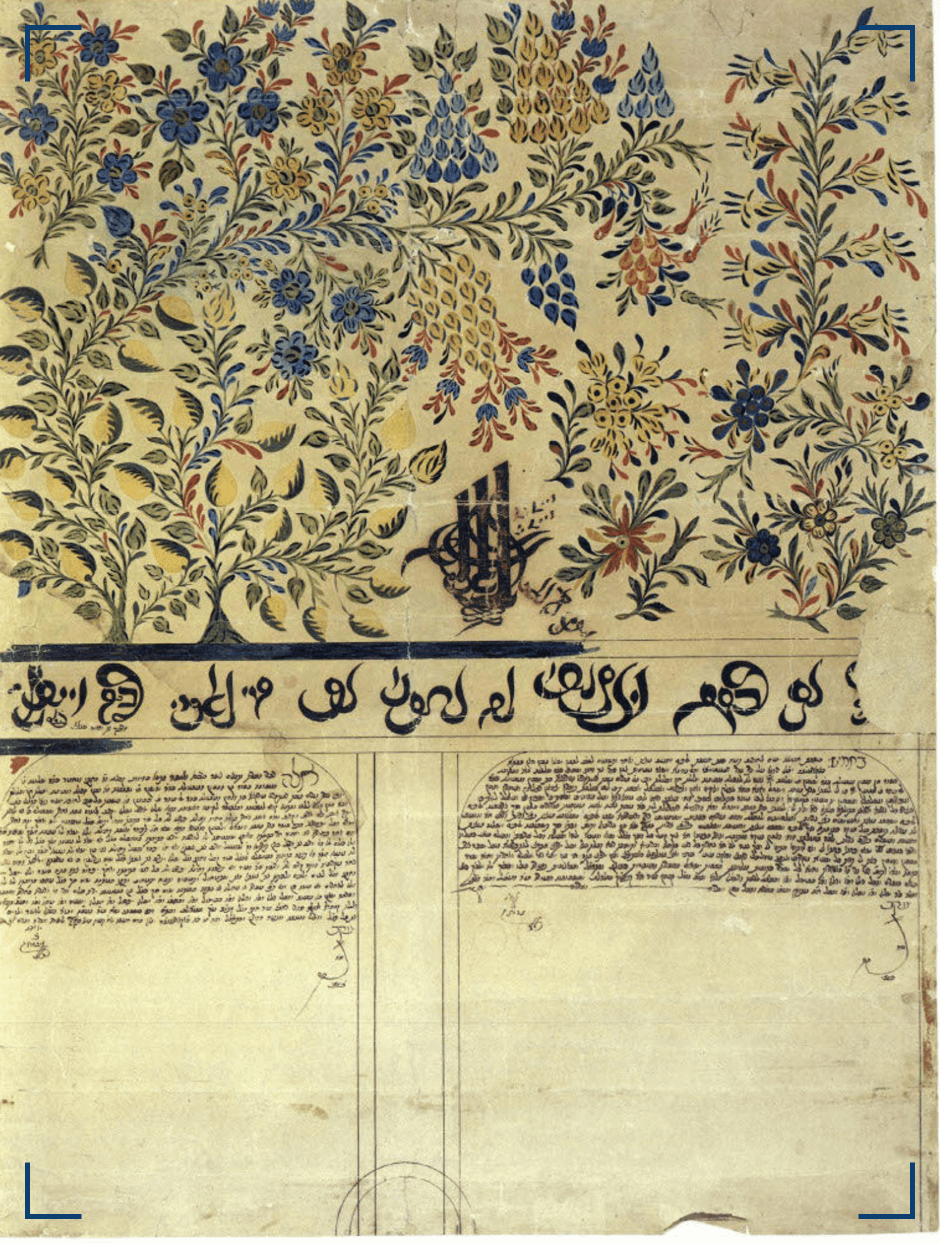

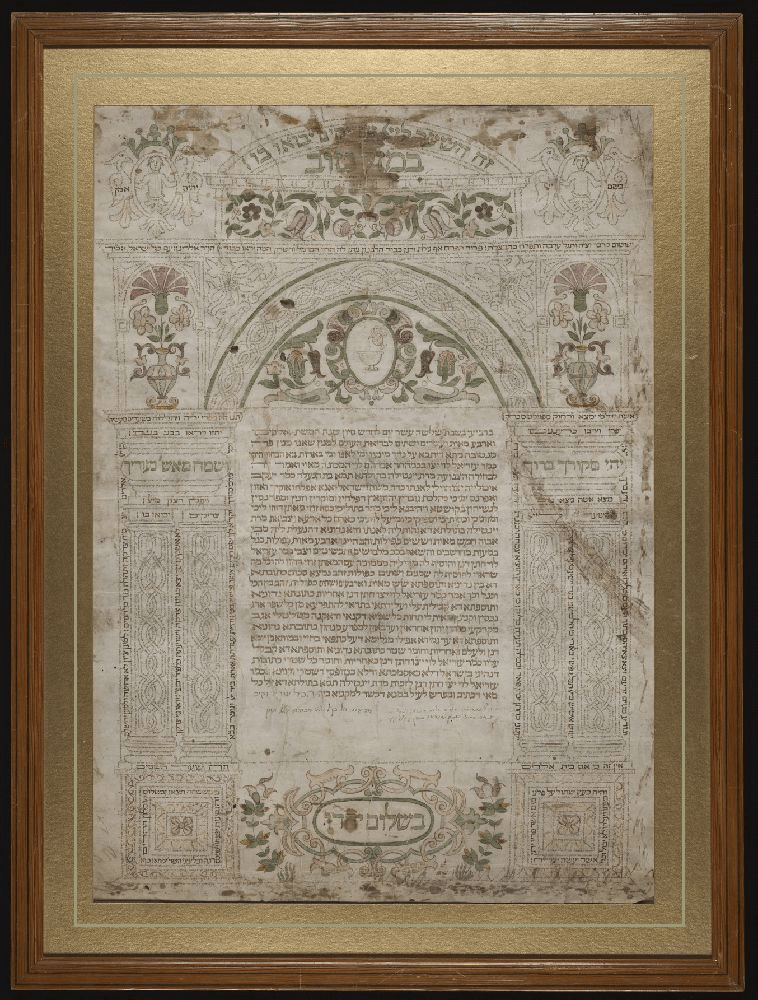

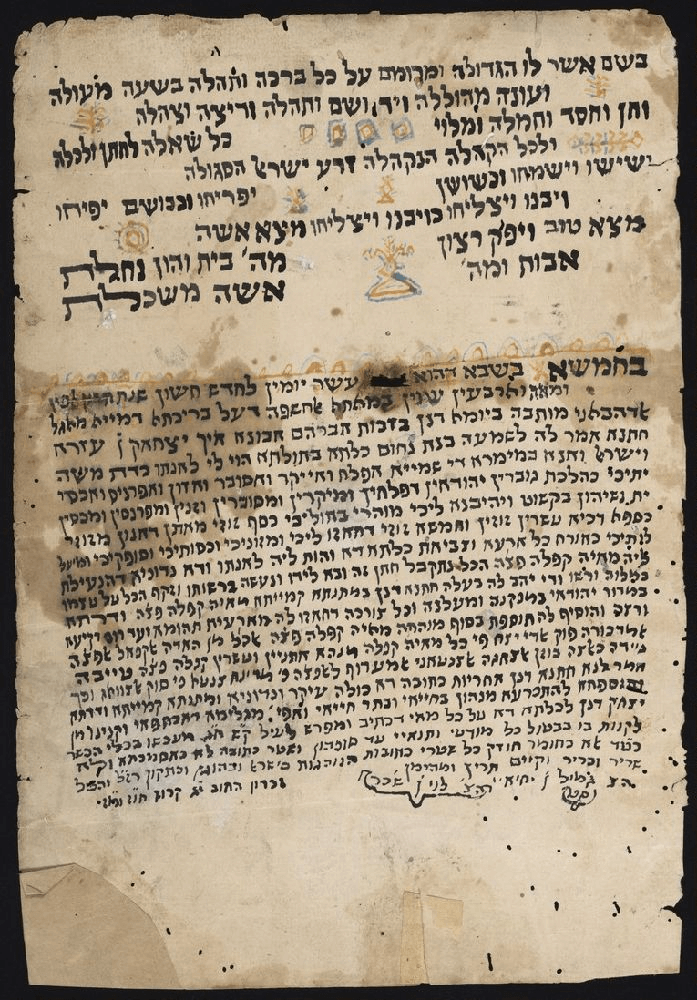

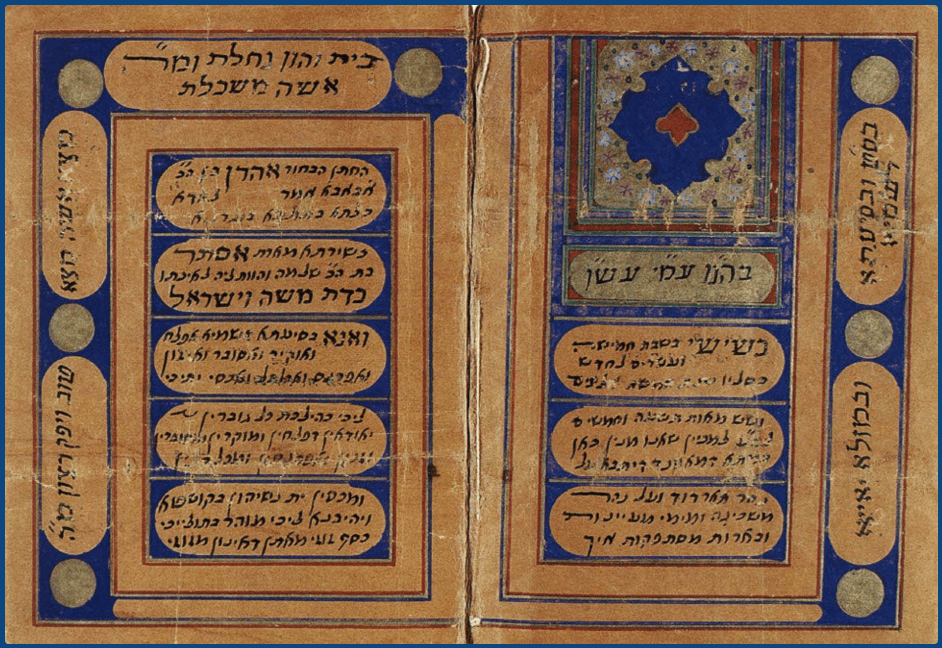

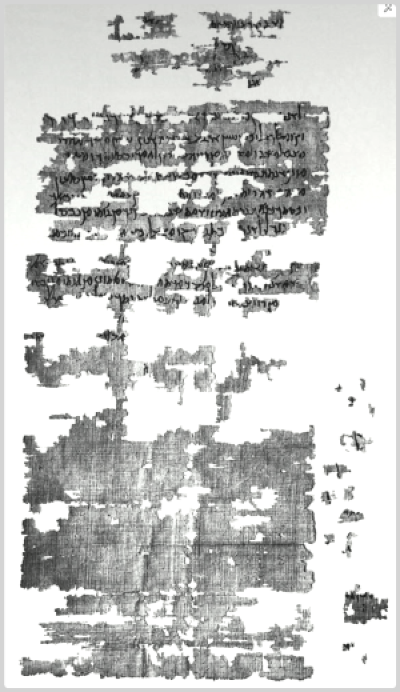

A lot of parts of Jewish wedding ritual come from the Torah, of course –and today we'll see some of what was, and how it's evolved. Today's post also includes a lot of images of ketubot– wedding contracts– because we've been making them for at least a couple thousand years, and they look all sorts of ways (e.g., the gorgeous example above.) And– we'll be looking at some patriarchal systems. Always with the both/and.

We're in Deuteronomy, preparing for battle. The Torah wants to make sure that everybody showing up can give 110%– and to stop anyone who shouldn't be risking their lives that day. There are a few invitations given, including this one:

"Is there anyone who has paid the betrothal gift (aras/done erusin) for a wife, but who has not yet taken her [into his household]? Let him go back to his home, lest he die in battle...” (Deuteronomy 20:7)

What's at stake about potentially dying in battle so close to finishing the wedding Love? Mutuality? Growth through a partner who challenges him? Nah: Descendants. For better or worse, this was considered the point of things in the biblical era, and beyond. So our recruit is told to go home and– seal the deal, if you will.

Back then, the crux of an engagement happened with the payment of a bride-price (the mohar) the money from the groom to the bride's father (some but not all of which was assumed to go to her). (1) Only later would the actual marriage take place.

By the Second Temple (and Rabbinic) era, this framework had evolved– the mohar became money held in trust for the bride in the event of divorce or widowhood, specified in the ketubah, the wedding contract. (2)

The ketubah is actually pretty brilliant– an ancient prenup that named the groom's obligations to the bride and detailed what property she brought to the marriage. It would make clear that the groom would be entitled to access any profits off of rent or wool from sheep or etc. that came in during their marriage, but in the event of divorce or his death, her principal (or equal value)– plus the amount owed in mohar, plus any additional financial gifts he might choose to make at this time – would go to her, with a lien on his property to ensure that this happened. This helped protect her, as well as to disincentivize frivolous divorces in a culture where women needed male protection.

This handing over of the mohar was called erusin. Engagement. (3)

Once erusin is performed, Jewish law says it can only be undone via traditional divorce (which is a big issue from a gender perspective and a site of a lot of Jewish legal activism now.) Because that's...messy... eventually erusin began happening at the same time as the second part of the wedding ceremony, nisuin. Nisuin is also known more informally as chuppah, the wedding canopy (which represents the couple's new home together.) (4)

We'll be spending a bunch of this piece talking about this whole erusin/betrothal business, but I'll just note that nisuin, the second half of the ceremony, is centered around seven wedding blessings– variations on relationship and covenant from the creation of the world to its redemption– all of time, in other words. In contrast to erusin, this shows us what partnership can be:

This is the sixth blessing:

"The loving partners shall rejoice as You caused your creatures to delight in the Garden of Eden of old. Blessed are you, God, who causes the [marrying couple] to rejoice."

The seventh blessing begins like this:

"Blessed are you, God our God, soverign of the Universe, who creates happiness and joy, [marrying couple]. Exultation, delight, amusement, and pleasure, love and fellowship, peace and friendship."

❤️

So before we proceed: There's so much that's so beautiful about the Jewish wedding ceremony. And a lot that's wild and been reinterpreted again and again – on Thursday, members of the House of Study will get a look at some of the origins of some other customs (and their possible relationships to demonology!)

(1) See, eg, the very TW:SA of Genesis 34:12, which talks about both mohar as well as matan, gifts from the groom directly to the bride. And we hear about (TW:SA) the mohar in Exodus 22:15-16. Ironically, one place we see this erusin language in the Bible is in the not-so-romantic Hosea (2:21-22) The Ancient Near East: Not the best place to be a woman.(2) More if she was a virgin, because then the paternity of any potential children would not be in doubt. And, you know, patriarchy and control and all that fun stuff. #whynotboth

(3) Erusin has the connotation of speech, like you're giving your word. And yes, we'll unpack all this ~gender~ as we go.

(4) Nisuin has connotations of "to carry," or "to take" presumably "take her into your home," cf the language in Deuteronomy. We see references to chuppah in Psalm 19:6 and Joel 2:16.

The Mishnah (Kiddushin 1:1) extends the biblical idea of paying the bride-price for the acquisition of a woman:

“A woman is acquired [in marriage] in three ways…She is acquired by money, by writ, or by intercourse. ‘By money,’ the School of Shammai maintain, a dinar [an ancient cash value] or the worth of a dinar. the School of Hillel rule, a peruta [another ancient value] or the worth of a peruta.” (1)

This idea of acquisition is developed in the Talmudic discussion on this mishnah (Kiddushin 2a-2b), when it asks,

"How do we know that money effects betrothal? By deriving the meaning of “taking” from the [verse about the] field of Ephron. Here it is written, “A man takes a wife” (Deuteronomy 22:13) and there it is written, “I give you money for the field; take it from me” (Genesis 23:13). Moreover, “taking” is called acquisition [kinyan], for it is written... 'They will acquire fields with money' (Jeremiah 32:44). Therefore, it is taught, 'A woman is acquired'…

The [mishnaic voice] initially uses the language of the Torah [that is to say, of acquisition, kinyan] and at the end uses the language of the Rabbinic tradition [that is to say, of dedication, kiddushin]. And what does the language of the Rabbinic tradition connote? That he [the groom] makes her forbidden to all [men] [mikudeshet] like something that is hekdesh."

There's a lot going on here! First of all, the text says that a woman is acquired in the same way that one might acquire a field—using the same means, i.e. money. They make that case through a game of verse analogies that you can track if you want, or let your eyes glaze over and trust me on it, whatever.

But: the fact that she’s being bought is pretty hard to avoid, here.

Secondly, it makes explicit the meaning of kiddushin. That's the Rabbinic word for the engagement ritual, aka erusin. Contrary to popular sentiment, the betrothal ritual is not named according to is ability to sanctify, [l’KDSH], the new union.

Rather, the woman is rendered hekdesh, forbidden to other men, just as an object that you dedicate to the Temple (made hekdesh) is forbidden for all other purposes. (This is a whole technical thing, but, like– once you declare that you're gonna give that one specific spoon to the Temple next time you're in Jerusalem, you're forbidden from using it to eat cereal. It can only be used from that moment on for Temple Stuff. Our bride has just been declared hekdesh viz other men.)

What is this acquisition? Some argue that the groom purchases the bride outright, while others—Judith Romney Wegner most famously—argue that he aquires her sexuality, the right to monogamy. Still others argue that he acquires not her, but rather the obligations of husband to wife, including those to feed, clothe, and have sex regularly with her.

"If [a man] takes another wife, he will not diminish [the first wife's] food, her clothing, and her conjugal rights." (Exodus 21:10)

Those– food, clothing, and sweet lovin'– are the obligations of the groom to the bride mentioned in the ketubah, the wedding contract.

In contemporary practice, this acquisition usually happens "through money," that is, by giving a ring worth a peruta or more– the ring is the money. So the groom traditionally places the ring on the bride’s finger and recites a formula of dedication/acquisition. (2) The bride need not utter a word, as her silence is understood to be consent to the acquisition. (3) Listen, it's great that they consider her consent at all. But the bar here is low?

Some people say that this is all symbolic, since it's not like you can sell your wife the way you can sell anything else you'd buy (including land, or livestock– another charming parallel the Mishnah draws). And the dinar/peruta thing is part of that. A dinar is almost 200 times the amount of a peruta. The reason the School of Hillel argued for the lower peruta amount is, according to Second Temple historian Zeev Safrai, that the whole thing was supposed to be symbolic so, to underscore that, they'd use the minimum amount possible for a transaction.

The School of Shammai used the higher number because it's bad to insult Jewish women.

(1) The "writ"/document here isn't the ketubah. The idea is that instead of handing over money, one can become betrothed by handing over a piece of paper on which the declaration of betrothal is written down in the correct way. We're not focusing on this in the piece today, just wanted to clarify.(1b) To not screw up the footnote numbering, I'll add here that LiST reader Batya Wittenberg wisely notes that Pirke Avot/The Sayings of the Sages (1:2) does include one instance of koneh/"acquire" with regards to a person that feels more egalitarian: K'neh lecha haver, acquire for yourself a friend. However, the Mishnah and Talmud's context with regards to this betrothal, as shown above, makes a different kind of case-- one on which many people have worked for decades-- so I don't believe that this one instance overturns my argument. However, I can absolutely see how a couple might choose to embrace this reading as the basis for a more traditional Jewish legal approach to Kiddushin. (2) See: Tur, Even Ha-Ezer 26; Maimonides Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Ishut 3:1; Shulchan Aruch, Even Ha-Ezer 27, 32, and the Rema on 32.

(3) Talmud Kiddushin 12b-13a, Maimonides Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Ishut 5:11, Shulchan Aruch, Even Ha-Ezer 2:4, Rema commentary, and others.

Needless to say, the thing about buying a woman unilaterally isn't great, and it then requires a Jewish divorce, which is in itself problematic – so this has led a number of people to work on the “kiddushin problem,” wondering what it might look like to have an egalitarian wedding ceremony in which the couple might be understood to be married Jewishly by some sort of recognizable standard.

When I was in rabbinical school, I fell pretty hard down this particular rabbit hole. (1) Which led the the creation of a website chronicling attempts to solve the erusin/kiddushin problem and trying to peel out pros and cons.

Taking ritual alchemy seriously means that it might not work to slap any old thing together in place of these ancient mechanisms for binding two people to each other. And taking LGBTQIA+ relationships seriously means finding a way for same-sex nuptials to have the same heft and substance that we assume straight weddings to have.

Fortunately, a few possibilities have emerged over the last 20 or so years that address the twin problems of feminist and queer weddings simultaneously, with varying degrees of dialogue with Jewish law. One way to sacralize the values of equality and egalitarianism is to make sure that weddings don’t require any particular gender to perform specific symbolic roles. (Of course, there are a wide range of gendered customs embedded in the traditional Jewish ceremony, so any couple that chooses to have the bride circle the groom or the butch cover the femme’s face with a veil has those options available.)

Should people use a partnership agreement? A lover's covenant? Should they make vows, instead? Do we look at how the bride can obligate herself to something sorta parallel that can be "acquired" in the ceremony? Should each partner acquire each other? What will be ritually and legally weighty, feel "correct," be egalitarian, protect the woman (especially if this is a straight wedding) from the horrors of Jewish divorce (2) deal with the acquisition issue, and work for the betrothed of any gender combination?

I used to feel strongly that Talmud scholar Rabbi Meir Simchah Feldblum's brilliant approach was the one– but, honestly, there are multiple possible solutions to the dilemma (though not all of them of equal strength, I'd argue.) I'm pretty sure the most updated listing of the approaches out there is here, which is, appropriately, a guide to same-sex weddings within the framework of Jewish law. (Needless to say, anything that would be good for two people of any gender combination would be egalitarian for a man and a woman!)

I imagine that with this, as with so many other ritual innovations and changes, the Jewish community will slowly come to favor one particular formulation of a new betrothal ceremony eventually – in ten or thirty years.

However they choose to get betrothed, I hope that when two people in love see one another under the chuppah, they have a ritual that represents the truth and integrity of who they are together.

(1) This happened in a number of ways, but I must particularly lift up my hevruta (tlatuta?) with the wonderful Rabbi Dr. Haviva Ner-David and Rabba Dr. Melanie Landau.(2) We will get there.

(Lotta resources at the end; keep scrolling! 💕)

🌱

Like this? Get more of it every week.

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, you get tools for deeper transformation, a community, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕

Especially without Substack's built-in network, word-of-mouth– forwarding emails, sharing on social media, etc– matters more than ever.

Please spread the word about this post and Life is a Sacred Text in general.

Thank you. 🙏 ❤️

Sign up for for the Life is a Sacred Text House of Study and get access to our MONTHLY ZOOM SALONS!

IRL opportunities to learn in community, and with Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg.

Next up will be The Accounting of the Soul:

A Personal And Communal Moral Checkup

What does our individual spiritual work look like this year-- for the mundane, the crucial but hard work looking at who and how we have been as individuals-- as well as communities and as a larger society? What might be different this year than in years past? These are days that require brave moral engagement, and during a time when so few seem to be-- we are, we must be, up for the task.

Join us for a lively, interactive conversation on questions that matter.

September 7th, 2pm ET/11am PT.

As always, when you sign up for the House of Study, you support the labor of indie Torah.

And if paying isn't on the menu for you currently, as always, hit up

support @ lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll happily hook you up.

The Chuppah

Marge Piercy

(full poem here)

"The chuppah stands on four poles.

The home has its four corners.

The chuppah stands on four poles.

The marriage stands on four legs.

Four points loose the winds

that blow on the walls of the house,

the south wind that brings the warm rain,

the east wind that brings the cold rain,

the north wind that brings the cold sun

and the snow, the long west wind

bringing the weather off the far plains....

O my love O my love we dance

under the chuppah standing over us

like an animal on its four legs,

like a table on which we set our love

as a feast, like a tent

under which we work

not safe but no longer solitary

in the searing heat of our time."

The old Kiddushin Variations site

For interfaith couples and families in formation, we help you build confidence in your relationship with Jewish. We understand Jewish interfaith relationships – and deliver knowledge and connection to help you open the door to Jewish in a non-judgmental way.