Blessing. Protection. Amulet.

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

As it happens, the oldest written versions of any of the texts that we have of the Hebrew Bible (so far) are in the form of... amulets.

In 1979, two silver Iron Age scrolls– dating to about 600 BCE, written in Paleo-Hebrew script, were found in archeological digs in Ketef Hinnom, a hill overlooking the Hinnom Valley, southwest of the Old City of Jerusalem.

They were written, as was everything in that time, in what's known now as Paleo-Hebrew, the old Hebrew script. (What we use now, the more blocky writing, is known as "Assyrian script," – theories about why it's called that are for another day.)

One of those amulets–both originally worn rolled up around the neck– involves a mashup of texts that we'd recognize from around the Hebrew Bible (Exodus 20:6; Deuteronomy 5:10; Deuteronomy 7:9; Daniel 9:4; Nehemiah 1:5).

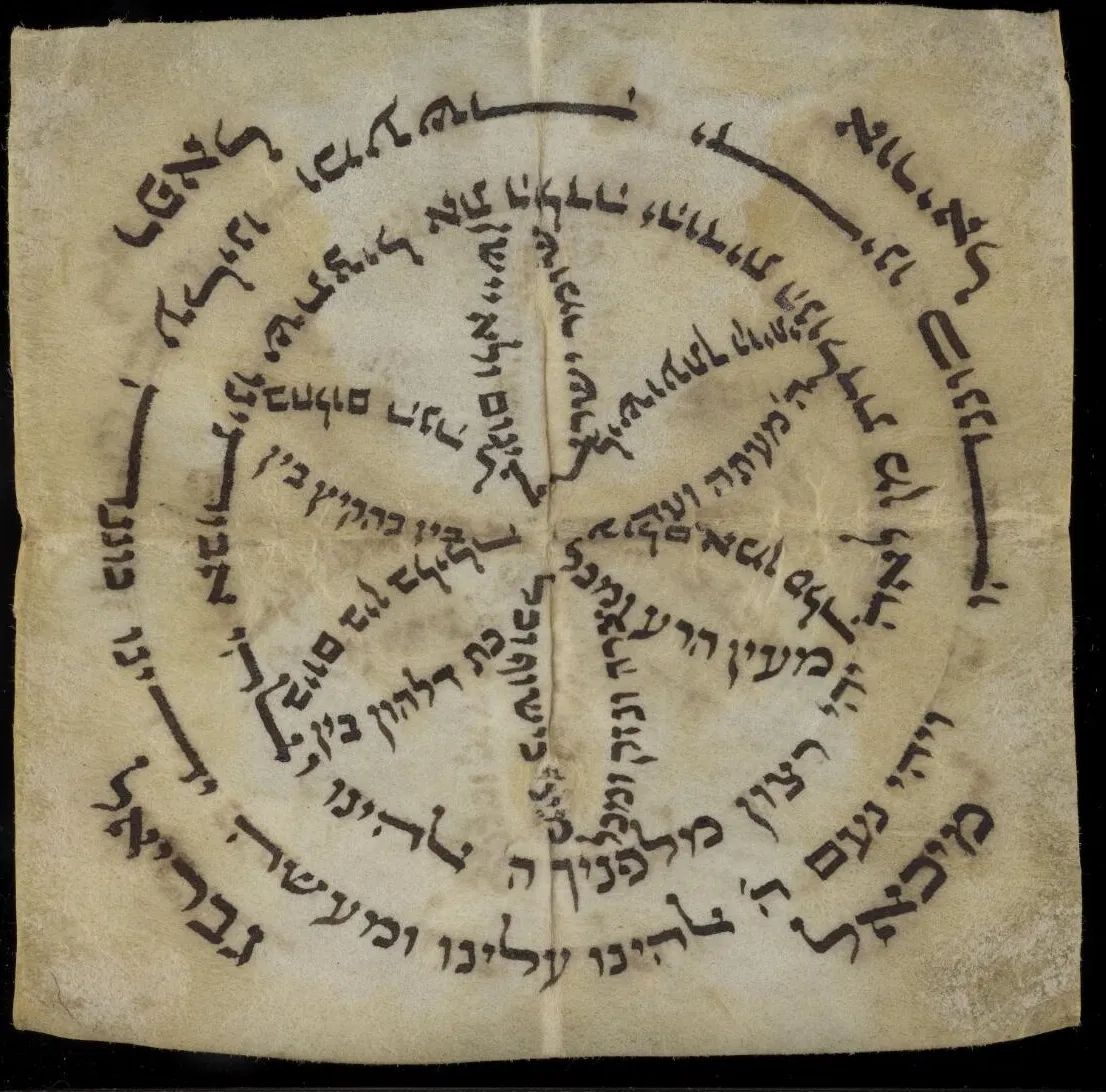

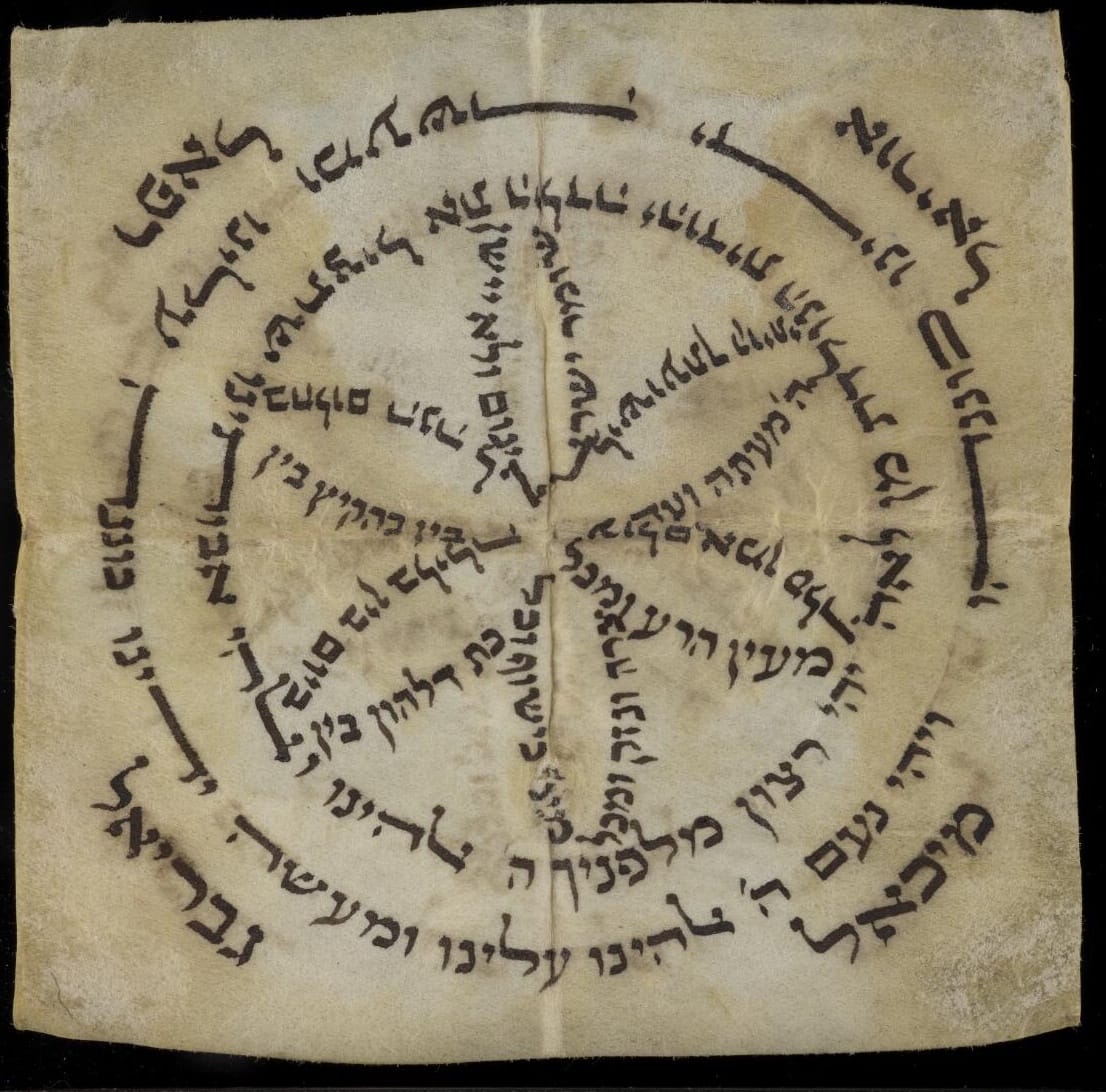

The other (photo above) involves one of the more famous and important texts in my tradition; what we refer to as the Priestly Blessing.

It appears in Numbers 6:22-26:

God spoke to Moses:

Speak to Aaron and his sons: Thus shall you bless the people of Israel. Say to them:

'God bless you and protect you!

God shine God's face upon you and show you favor!

God lift up God's face towards you and grant you shalom/peace/wholeness!'

I've included below the English, Hebrew and Paleo-Hebrew of what was found on the Ketef Hinnom scroll, since it's cool to see. I've translated the Tetragrammaton as "God," as I always do, but know that we are absolutely dealing with the Divine Ineffable Holy Name here, the one we don't say, the most intimate and unsayable of them all. (1)

- h/hu. bless the/- 𐤄/𐤅 𐤁𐤓𐤊 𐤄 ה/ו ברך ה

- -[e] by Go[d] 𐤋𐤉𐤄׳ [א] לו[ה׳

- the warrior/helper and 𐤄𐤏𐤆𐤓 𐤅 העזר ו

- the rebuker of 𐤄𐤂𐤏𐤓 𐤁 הגער ב

- [E]vil: Bless you, ]𐤏 𐤉𐤁𐤓𐤊 [ר]ע יברך

- God, 𐤉𐤄' ה׳

- keep you. 𐤔𐤌𐤓𐤊 שמרך

- Make shine, Gd- 𐤉𐤀𐤓 𐤉𐤄' יאר יה

- -[W]H, God's face ]𐤄 𐤐𐤍𐤉𐤅 [ו]ה פניו

- [upon] you and g- ]𐤉𐤊 𐤅𐤉 [אל]יך וי

- -rant you p- 𐤔𐤌 𐤋𐤊 𐤔 שם לך ש

- -[ea]ce. ]𐤌 ל]ם

From the perspective of Professor Jeremy Smoak, the use of the Priestly Blessing was, in large part, "apotropaic"– having the power to avert evil– and suggests that during the First Temple period, priests would not only recite the blessing at the Temple, but (as these discoveries show us) inscribe them on amulets so that Israelites could use them as part of their everyday life.

The act of giving this blessing was about more than just "saying nice words."

These words were meant to effect change in the universe.

To offer actual protection.

When the priest said, "God bless you and protect you," he was, in effect, drawing down from the divine to offer that blessing and protection, in real time, to the people present.

And so, too, in the writing of the Priestly Blessing on those amulets.

As Rabbi Dr. Alan Brill (also here) put it,

"Going all the way back to Second Temple times [during which the practice of the Priestly Blessing continued], we are clear on the power in the Divine names. We have no tractate [in Rabbinic literature] on the power of Birkat Kohahim/the Priestly Blessing, but there is an overarching general sense from the Rabbis that the Divine Names and Psalms have power.

It is unarticulated but understood."

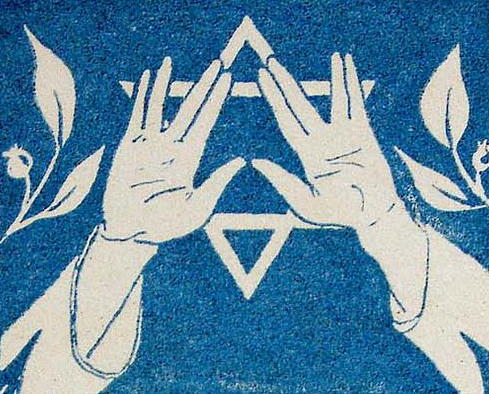

The recitation of the Priestly Blessing is still a Jewish practice. Now those who are kohanim, descendants of the High Priest, (2) may give the Priestly Blessing in synagogue. Many parents still give this blessing to their children every Friday night, as well. (It's also said at other times; this isn't an exhaustive list.)

Prayer is a communication between a person and the Great Everythingness; it’s an offering up, and sometimes a sort of a receiving.

Blessing, on the other hand, is something that we can give over to other people—something we bestow on one another.

The Ketef Hinom scrolls are tiny. The one in the photograph above– unrolled– is 1.5 inches tall and 0.4 inches wide. And the writing on it is deliberately meant to be difficult to read; it was scratched very lightly in by someone with profound skill.

As Professor Smoak put it:

Miniatures—especially those worn on the human body … create a sense of intimacy, privacy, and personal time between the body and the object. Such objects became part of one’s daily routine and lifecycle. Their lightweight quality allows them to dangle comfortably from necks, producing a feeling that they are part of the body. In the case of miniature texts on jewelry, this means that even though the writing might be invisible or hidden from eyes, the words are always accessible in the wearer’s mind as the writing interacts with the body on a physical level. As the jewelry dangles from, bounces off, and returns to the body, the words inscribed on their surfaces are replayed in the mind.

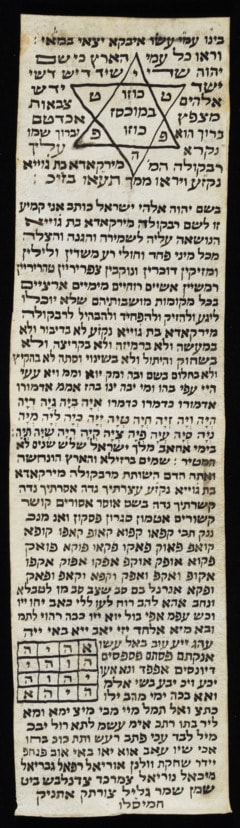

And this use of the Priestly Blessing for protective purposes– in not only liturgical, but in written form– continued on and on throughout Jewish history, as this amulet from 18th-19th c. Italy offering protection from the Evil Eye for a mother and her new child attests:

The following story was told regarding Rabbi Kalfon Moshe HaKohen (1874–1950), of Djerba (Tunisia):

"His granddaughter, who experienced difficult births and repeated miscarriages, begged him to write an amulet for her, and after repeated entreaties, he conceded and wrote for her an amulet with plain ink, on plain paper, and it was very beneficial for her, as well as for other women....When the amulet was opened, it was found to contain only the three verses of the Priestly Blessing… No Holy Names, no illustrations, and no [other fancy stuff]" (Peninei HaParasha, VIII, 2007, issue 398).

Just the Priestly Blessing, written on their equivalent of a legal pad with a ballpoint pen. But it nonetheless Did The Thing.

As I've been digging around for this piece, it's been... well, somewhere between frustrating and enraging to discover how many sources that write about amulets also condescend about the use of amulets.

"Why should we study these folk practices??" one website (with an incredible archival collection) wondered, before waxing rhapsodic about the sociological insights they offered. Other places that– similarly– housed invaluable primary materials managed to sneak the words, "superstition," or even "primitive beliefs," into their framing.

Like: You guys know that you are institutions and organizations dedicated to the study and preservation of Judaism, right? You know it's noxious to make fun of the things you're preserving, and a bad look to be that incurious about why amulets are so deeply woven into Jewish textual and cultural life across time and our global cultures?

Because, yeah, amulets are certainly not just a 600 BCE thing, as the last couple of anecdotes, above, indicate.

The Mishnah (Shabbat 6:2) teaches that one may only go out with an amulet on Shabbat if it was "written by an expert." (Rest of the week? Different story.)

And the Talmud (Shabbat 61a) teaches, on the subject of what amulets are OK for Shabbat, specifically:

The Sages taught in the Tosefta: What is an effective amulet? It is any amulet that healed one person once, and healed them again, and healed them a third time. That is the criterion for an effective amulet, and it applies to both a written amulet and an amulet of herbal roots; both if it has proven effective in healing a sick person who is dangerously ill, and if it has proven effective in healing a sick person who is not dangerously ill. It is permitted to go out with these types of amulets on Shabbat. And an amulet was not only permitted in a case where one has already fallen due to epilepsy and wears the amulet in order to prevent an additional fall. Rather, even if one has never fallen, and they wear the amulet so that they will not contract the illness and fall, they are permitted to go out with it on Shabbat.

You catch that? Both written and herbal-based amulets (as various herbs were regarded as having medicinal/protective properties) are kosher, but to wear it out on Shabbat, you had to make sure it's already worked– unless you're someone who might really need it to help keep them safe.

Later Jewish law, like the important 16th century code the Shulchan Aruch (Orech Chayim 301:25, eg), cheerfully advises on when amulets can be used, and in what way, with both Rabbi Yosef Caro– a Sephardi rabbi writing from the Land of Israel– and the Ashkenazi Rabbi Moses Isserles, writing his additions on Caro's work from Poland– agreeing, overall, on what designated an amulet– and amulet-maker– efficacious. (3)

In any case, all these Torah scholars endorsing amulet use– plus all these gorgeous images that you've now scrolled through– bring us back to this other question:

So on the very off chance that literal millennia of Jewish history weren't full of people who were stupid, deluded, or foolish– then how might we understand what amulets are?

So here are a few takes, from a few brilliant folks:

Rabbi Dr. Brill began here:

A kamea/amulet has power in the same way that a Torah scroll and tefillin have power– it is infused with sanctity and holiness.

God can be channeled into objects and used; this is an indirect use of divine powers. And a kamea/amulet is about receiving divine energy.

We tend to distinguish between talisman and kamea/amulet– a talisman has half a foot in a "charm." A kamea invokes a blessing on you, specifically. This happens if you clearly go to someone who writes you something specific to your needs, with a specific combination of angels, divine names, your needs, your name. Kameot are very contextual – those done for pregnancy are not done for sickness are not done for success for work. It's not like a red string or a hamsa that is purchased for generic protection."

Dori Midnight, who does a lot of work around reviving Jewish ancestral practices, puts it like this:

Amulets are known as קמיע kame’a in Hebrew, bulsika in Ladino, beytele in Yiddish, and تميمة/tamīma in Arabic. The word kame’a can describe various kinds of amulets for protection and comes from the root that means to bind, knot or hang upon. Often worn around the neck, slid into a pocket, or hung above a doorway or bed, amulets hold a sense of connection to ourselves, each other, the maker, the elements and divinity.

The protective power of an amulet is not outside us, but rather places us inside the interdependence we are already woven into. The making and gifting of amulets can be a way of generating and feeling community resilience. [The act of amulet-making can sometimes be understood as a kind of] embodied ritual technology that transmit care from our hearts through our hands into the object, orienting us towards connection.

Rabbi Jericho Vincent (also here) puts it this way:

When we make an amulet, it becomes a spiritual/material fusion to focus, articulate, and symbolize our deep intentions for healing, protection, abundance, or whatever– with the hope that it will spiritually/materially activate a particular frequency of Divine energy in ourselves, the Divine energy between ourselves and other beings, and the Divine energy beyond all beings.

Ancestral amulet practices have a particular power, because they’re saturated with the ancestors' hopes, fears, and dreams, and there can be mysterious and intense amplification of our own intention when we connect it to the intentions of those who came before us and still live on in our DNA, in our intergenerational inheritances, and in the spirit world.

The amulet that we saw at the top of the post, with the case in which it was carried. If you look carefully, you can see that it was folded into quarters, then put in this little leather pouch, onto which the name of the baby--Yehudit--was inscribed. The hole at the top of the pouch enabled one to string it and tie it around the baby's neck or elsewhere. (I hate that there's no alt-text on the gallery feature--hopefully my description here suffices.) NB my other fave from this collection, the amulet for protecting the house from scorpions, snakes and other harmful creatures.

The last possibility I'd like to suggest in terms of the creation and use of amulets that some very smug academics seem to have discounted is that... we might just not know everything anymore.

There are, of course, still Jews who use amulets now, today (4), and/though modernity, colonialism, world wars, globalization and more have changed so many ways of thinking and being and doing, and we have all lost so much ancestral wisdom across communities, across the globe.

Even if we do the same practices, there may be ways of engaging with those practices that have been lost– that just as there were things that were, to the Rabbis, "unarticulated but understood," so too may there also have been things that were obvious to earlier generations that escape our grasp from over here.

Part of the task of engaging with our traditions in their fullness is having the humility to remember that the encounter with the Unknowable has taken many, many forms over the centuries, and that we may have only had the opportunity to taste the thinnest sliver of what's possible–

but that does not mean that we should ever give up the effort to seek, and to find,

to learn, and to try to experience,

to know, to connect, and to offer,

To give over blessing–

to receive blessing–

in all the ways that we can.

🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week. 🌱

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, that's how you can get tools for deeper transformation, a community for doing the work, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕

FOOTNOTES

[1] Ketef Hinnom scroll

[2] Descendants of the Priestly caste

[3] Jewish law and amulet making

[4] Jews who use amulets now today

The missing bits reflect what couldn't be clearly identified, and the funkiness is their uncertainty re: what letters are what, I think.)I've also edited God's name in the Hebrew and Paleo-Hebrew, per our reticence to write out the Tetragrammaton unless absolutely necessary. (Note that the missing parts both in the middle and after what we have may have been in the parts where the scroll disintegrated. ↩︎

Yes, we're such a weird people that if a Jew's ancestors 2000 years ago were kohanim or leviim-- priests or Levites-- they very likely know it. Sometimes it's maintained in a last name (Coen, Cohen, Kahane, Kohn, Kahn, Katz, sometimes also Kaplan, Kagan, Rappaport, etc. and Levi, Levit, Levinsohn, Lewinsky, Levinstein, Lévy, Levine, Lewin, etc.), sometimes not. And increasingly there has been a movement for the inclusion of women in these lineages as well, particularly when it comes to access to things like the privelege of giving the Priestly Blessing. ↩︎

So there's a whole question about the important non-Kabbalist legal scholars (we'll talk about why I don't call Maimonides a "rationalist" some other day)-- on the one hand, Maimonides talks as casually about amulet use as his later mystical buddies in the Mishneh Torah (EG Torah Vessels 7:11 and 8:6, Shabbat 18:14, 19:14, 26:14, etc. etc.) But he also writes in the Guide for the Perplexed (1:61): "You must beware of sharing the error of those who write amulets. Whatever you hear of them or read in their works, especially in reference to the names which they form by combination, is utterly senseless...." Sooo... ? Amulets good, Maimonides? Or ... ? (Do you feel suddenly less guided and more perplexed??) Rabbi Rachel Salston explains what's going on:

"[Maimonides] is critiquing the use of codes in [amulets] to form what are often called shemot (names of God). He is vehemently opposed to assigning any sort of transcendent power to any name other than the Tetragrammaton. The use of codes, even when they innocently conceal verses of Hashem’s Torah, can easily come to represent new “holy” names." There's a lot more to say about Maimonides' theology, especially in that chunk of the Guide, but if you know him you could see him getting itchy about people referring to specific properties of the Divine after he'd laboriously explained why that's Not A Thing. ↩︎And people of other religious traditions, of course-- but we need to be careful not to over-generalize, to assume that this thing means the same thing accross cultures and traditions (just as prayer is not one thing, just as observing holy days are not one thing). And there's enough to parse, enough ways that I have run roughshod over the fact that there are a multiplicity of Jewish cultures and a multiplicity of Jewish ways of being and doing. Amulet-making has undoubtedly not been the same thing in every Jewish culture around the globe, or even every era of every Jewish culture. It was undoubtedly not the same thing in 19th c. Morocco or Ukraine (different as those places and cultures are from each other!!) as it was in 600 BCE Jerusalem. Just as there are a range of Jewish ways of praying, and thinking about what prayer is and does, so too do I assume that there are a myriad of ways of thinking about, and experiencing this. AND YES, of course we can talk about what Jewish Moroccan amulet-making may have had in common with that of its Muslim neighbors, and all the other relevant analogies therein, but there are only so many cans of worms, so many footnotes, and so many places for me to over-extend my extremely limited expertise, here. ↩︎

Because I cannot help myself, here's a Cohen gadol– a great Cohen– reciting the Priestly Blessing. It is not the traditional recitation, by a long shot (a lot of things, including but not limited to holding up his hands just at the end)– honestly, I don't feel comfortable sharing a video of the real thing. It's a little too much 'anthropology of sacred rite' for my tastes. If it was meant to happen in holy space, let it happen there.

This happened in a massive concert hall full of people who understood and participated in its meaning, and was just right for what it was.