eye for an eye?

or: let's hear it for textual activism

This is Life as a Sacred Text, an expansive, loving, everybody-celebrating, nobody-diminished, justice-centered voyage into one of the world’s most ancient and holy books. We’re generally working our way through Leviticus these days. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here.🌱

“An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.”

This statement is commonly attributed to Gandhi; as far as I’m aware, there is not definitive proof that he ever said those words. That is to say, his biographer, Lewis Newman, used them, but it’s unclear from context if Newman was a paraphrasing and/or quoting Gandhi himself, or if this was Newman’s own articulation of the Mahātmā’s philosophy, formulated as a response to this passage:

And if a person maim their neighbor; as has been done, so shall it be done to them: break for break, eye for eye, tooth for tooth; as a person gave an injury, so shall it be rendered unto them. (Leviticus 24:19-20)

We do know that in 1914, when the politician and journalist George Perry Graham was arguing against the death penalty in the Canadian House of Parliament, he said this:

We can argue all we like, but if capital punishment is being inflicted on some man, we are inclined to say: ‘It serves him right.’ That is not the spirit, I believe, in which legislation is enacted. If in this present age we were to go back to the old time of ‘an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth,’ there would be very few hon. gentlemen in this House who would not, metaphorically speaking, be blind and toothless.

Whether or not the more bumper-sticker friendly quote is really Gandhi’s, Leviticus 24:19-20 is not infrequently invoked as an example of the absolute worst kind of justice. (The same phrasing, more or less, also appears in Exodus 21.)

For example, antisemitic rhetoric that refers to the “angry, judgmental Old Testament God,” in sharp contrast to the “nice, kind, loving New Testament God,” often cites this passage as prooftext, since the concept of “turning the other cheek” came as a commentary on these verses:

You have heard that it was said, ‘an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I say to you, Do not resist the one who is evil. But if anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also (Matthew 5:38-39, ESV translation)1

Never mind, as we have seen, that loving one another, and caring for them, is a pretty big value in the Hebrew Bible (please don’t ever call it Old Testament, OK?)2, and the God described in parts of the Christian Bible, like the Book of Revelation, is kind of terrifying?

Nevertheless, antisemitic invective often invokes “eye for an eye” as the kind of proof that Jews are harsh, brutal people lacking in compassion and love.

Never mind how Jews have dealt with this verse, or the context in which it lives.

Time to investigate these things, no?

So, again, Leviticus:

And if a person maim his neighbor; as has been done, so shall it be done to them: break for break, eye for eye, tooth for tooth; as a person gave an injury, so shall it be rendered unto them. (Leviticus 24:19-20)

The Exodus passage goes a little further—interestingly, using the verses that form the foundation of Judaism’s approach to abortion. The bottom line for this set of verses is: if a miscarriage alone is caused, financial damages are paid, but if the pregnant person dies, the case is treated as manslaughter. (AKA the fetus is not regarded as having the full rights of “personhood” in this text—it is seen as potential life.)

If men fight, and hurt a pregnant woman, so that a miscarriage results, and yet no further harm follows; the one responsible shall be surely punished, according to what the woman’s husband may exact from him, the [financial] payment to be based on reckoning. But if other damage ensues, the penalty shall be life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, wound for wound, bruise for bruise. (Exodus 21:22-25)

I mean. It sure sounds pretty bad, doesn’t it?

And while I’m not here to defend this kind of pure lex talionis (law of retribution), I am here to complicate our thinking about these verses—what they’re doing there, why, and what the Jewish tradition has done with them over the centuries.

So to begin, it helps to understand where these laws came from-but we gotta go wayyy back.

Hammurabi (1792–1750 B.C.E.—yes, close to 4000 years ago) was the sixth Amorite king of Old Babylon. He conquered a bunch of land (almost all of Mesopotamia), dethroned the Assyrian king and, most famously, wrote some laws.

Hammurabi’s Code is famous for being one of the first comprehensive law codes—and was certainly the first to deploy a presumption of innocence. Among other things, it included a bunch of penalties for the perpetrator of harm—presumably to limit the scope of retribution when something bad happened. (Like, say, if you poke my eye out, the Code prevents me from killing your whole family, at which point we start waging a war of honor between familial groups3, etc.)

It’s not an accident that a lot of Hammurabi’s laws sound an awful lot like Torah texts—with a twist—even though they likely predate the authorship of these verses by about a thousand years.

Like, check this out:

209 If a man strikes a daughter of a man (mārat awīlim) and he causes her to miscarry her fetus, he shall weigh out ten shekels of silver for her fetus.

210 If that woman dies, they shall kill his daughter.

So: a pregnant person is struck, there is a miscarriage, financial damages are paid. (Notably this scenario doesn’t involve someone getting accidentally knocked over; a more direct hit is implied.) But if she dies—instead of the perpetrator getting the death penalty—”life for life.”—his… daughter is killed. Whew.

And we also see:

196If an awīlum (a free man), blinds the eye of a member of the awīlum class, they shall blind his eye. 197If he breaks the bone of an awīlum, they shall break his bone.

198If he blinds the eye of a muškēnum (one economically obligated to the palace)[13]or breaks the bone of a muškēnum, he shall weigh out one mina (sixty shekels) of silver.

199If he blinds the eye of an awīlum’s slave (wardum; a slave held as property) or breaks the bone of an awīlum’s slave, he shall weigh out half of his value.

200If an awīlum knocks out the tooth of an awīlum of the same rank, they shall knock out his tooth.

201If he knocks out the tooth of a muškēnum, he shall weigh out one third mina (twenty shekels) of silver.

So we have the blinding, the breaking, the tooth-knocking that we’ve seen alluded to in the Torah texts—but spelled out sentence by sentence. Almost as though the Torah presumes that its reader is familiar with these laws and pulls together something of a shorthand alluding to them. But here, in Hammurabi’s Code, it’s clear that the status of the person harmed is relevant. That grisly equal retribution only kicks in if someone has harmed high-status people; otherwise, presumably, Hammurabi did not value their lives or suffering as much.

In the Torah? Not so much. Seems that everyone is regarded equally with regards to injuries, harm, in contrast to Hammurabi’s Code. Everybody is someone who matters. (Though it would have been nice if everyone was someone whose harmdoer would not be mutilated or killed as punishment, obviously.)

So what happened? Is the Torah just a copycat, or what? Does this mean that the Torah dates to Old Babylon?

It seems likely that the following is what happened:

Assyria—the neo-Assyrian empire—conquered the northern kingdom of Israel in 722 BCE and the southern kingdom of Judah 701 BCE. Copying Hammurabi’s Code was standard practice for Assyrian scribes-in-training, and likely the ideas themselves were still in heavy circulation at the time. So the Jews (well, Judeans/Israelites)4 had heard these laws, and integrated them into their own texts, with a twist. We’re not going to kill your daughter, who is innocent! For example.

And as Prof. David P. Wright, Professor of Bible and Ancient Near East at Brandeis University put it, the Torah texts

appear to operate as a response to the politically dominant Assyrian power by adapting Mesopotamian cultural motifs as part of Israelite/Judean heritage. The degree that this response sought to acquiesce to imperial power by emulation or to subvert it is open to debate. But a strong hint that this is an expression of resistance is found in [the Torah’s] replacing the royal human lawgiver (Hammurabi) with the national deity [God/the name that goes with the Tetragrammaton] and setting this revelation of law at the nation’s birth.

Got it? So the Torah texts may well be an expression of resistance against the oppression of a foreign empire. “Yeah, well, our law system treats everyone as important and our ruler is God, not you punks.”

(Relatedly, there are some who suggest (cf Midrash Numbers Rabba 2:9) that our pointing at the Torah when it is lifted (now manifest as that pinky finger thing) comes from the ancient Roman pointing salute, which people would use when the the Roman emperor passed by—another way for Jews to say, ”This is our ruler, not you!”)

This history already changes how you think about these verses, doesn’t it?

It does for me, anyway. Again, not that retribution is the world we should live into, but context truly is so much.

But, of course, we it’s important to see what happens in the Rabbinic era, as the Rabbis post-Temple try to consider how these verses should be lived out in their day-to-day:

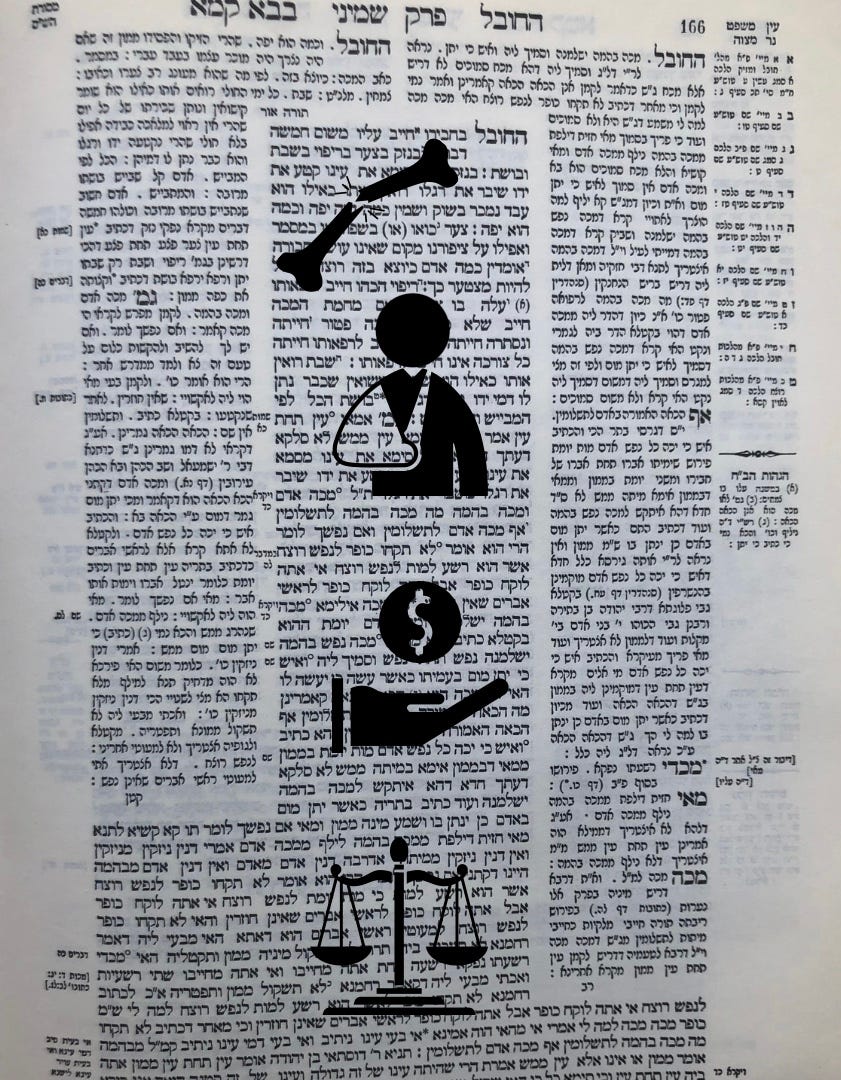

The Mishnah (Bava Kamma 8:1) teaches :

The one who injures a fellow is liable for five things: For injury, for pain, for healing, for the loss of time [at work], and for humiliation.

Got it? If I hurt you, I need to pay five different kinds of damages—not just amends for the injury or for the suffering caused, but also medical care, wages for any work missed, and for possibly humiliation—emotional damage—suffered.

At which point the gemara (aka the Talmudic commentary) comes in with the following, beginning in the voice of the anonymous (stam) redactor of the Talmud:

Why [only monetary repayment]? The Merciful One says [in Torah] (Exodus 21:24) "Eye for an eye"! You might say that this means an actual eye [should be taken as payment for someone else’s eye being irrevocably harmed.]

That interpretation shouldn’t even enter your mind! For, it was taught [in a Baraita, a source contemporary to, but less authoritative than, the Mishnah]: "[One might have thought that] one who blinds an eye has their eye blinded, that if they amputate a hand their hand is amputated, that if they break a leg their leg is broken. The Torah teaches, (Leviticus 24:21) "Whoever (lethally) strikes a person," and also "Whoever (lethally) strikes an animal..." Just like the striking of an animal is subject to [monetary] repayment, so too the striking of a human is subject to [monetary] repayment. (Talmud Bava Kamma 83b)5

What the Baraita here is doing is called a gezera shava—taking a principle from one verse and applying it to another verse that has the same kind of language. Making a Jewish legal hyperlink between the two, if you will. Since both the animal and human verses have similar phrasing, the Rabbis assert, you can apply the consequence set out in one verse to the other.

And there’s even a little bit of word play—an eye for an eye, literally (ממש/mamash?) Or do you just pay money (ממון/mamon)?

Do you see what they’re doing?

This is textual activism.

That is, the Rabbis are finding a way, by using a close reading of the Torah and their accepted rules of interpretation to state, definitively, that “an eye for an eye” means that, instead of a court-mandated poking out of the harmdoer’s eye, the harmdoer is directed to pay financial damages to the person whose eye was poked out.

Hopefully you see that this interpretation is a choice that they make. They easily could have not only chosen to read the verse literally, but to even do the reverse—to conclude that, based on the verse about humans, one must issue the death penalty for the murder or manslaughter of dogs (dogslaughter?). Seems pretty plausible, and yet the Rabbis made a different choice. And offered no fewer than ten different arguments to make their case (when often one or two is all you’ll get).

For example (bold is original language, Roman is Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz’ additions for clarity):

It is taught [in a Baraita]: Rabbi Dostai ben Yehuda says: The phrase: “An eye for an eye” (Leviticus 24:20), means monetary restitution. Do you say that he must pay the victim monetary restitution, or is it only teaching that the one who caused the injury must lose an actual eye? You say: There may be a case where the eye of the one who caused the injury is large and the eye of the injured party is small. How can I read and literally apply the phrase “an eye for an eye” in this case? The Gemara continues the derivation: And if you would say that in all cases like this, where their eyes are different sizes, the injured party takes monetary restitution from the one who caused him injury, but in a case where their eyes are the same size, the one who caused injury is punished by actually having his eye removed, this cannot be, as the Torah said: “You shall have one manner of law” (Leviticus 24:22), teaching that the law shall be equal for all of you. (Baba Kama 83b-84a)

So one argument for this radical reread is so suggest that this ancient way of punishing isn’t egalitarian, because the loss of an eye, or anything else, could theoretically be deeply unequal, and that won’t work for creating justice.

The Rabbis’ choice to even ask the question—”An eye for an eye—mamash (literally) or mamon ($$$)?—is radical and profound.

And they then chose to use all of the tricks and tools at their disposal in order to bring a more compassionate possibility into being.

As Rabbi Benay Lappe put it, the Rabbis’

interpretive tools… were meant to be handed down from one generation of tradition-shapers to the next. The “stitches” are the talmudic techniques [such as gezera shava]…. These are the tools the tradition is passing down to us to use as, and when, we need to, to upgrade Torah so that it will do a better job of creating the kinds of people who will make a more liberatory world….

When the in-the-know student sees that [this Talmudic discussion] consists of not a single proof, or even two proofs, but no fewer than ten proofs for the claim that “eye for an eye” means money for an eye, they know that while the “cityscape” looks like the message “‘An eye for an eye’ always meant money,” the meta-message is this: we don’t need the Torah’s approval to upgrade the tradition so that it does a better job of creating the kind of people we want to create, and the kind of world we want to live in—namely, in this case, one in which we invest in just, restorative systems for addressing harm.

The Rabbis ask new questions: What is justice? How can we address the wrong that's happened but not create other kinds of suffering? How can we move past the old winner/loser model to a more nuanced way of resolving problems, moving forward?

For one who has cut off the hand of another, we can ask what can bring healing, what can create a world in which there is more justice. The suggestion is not to abandon the need for amends, but rather to see if we can let go of the need to hurt the person who has caused hurt—to try to figure out how we can best heal one another, and the situation as a whole.

Every read of text is an interpretation. Every single one.

We can choose interpretations that bring us closer to each other, to justice, to the divine, the holy, the future that we would like to see.

Or we can choose interpretations that willfully harm others, that excuse and justify without taking moral responsibility for the fact that this read is, as everything, a choice.

Think of how some people (of either Jewish or Christian variety) point to Leviticus 18:22 to (unjustly) justify horrific homophobia that has hurt untold queer people over the generations and yet somehow the Hebrew Bible’s commandments become a lot less relevant and/or urgent for them the moment anyone suggests that they might need to take that “loving the stranger in your midst” business seriously.

But, again: Every interpretation is a choice. The choice to find compassion, the choice to clobber.

The choice to support dominant power or the choice to resist oppressive forces.

Torah is sacred, and it's for good reason that we point in reverent salute when it’s lifted up.

What's holy, for Jews, is not only the words of Torah that we have been given, but the process of doing Torah that is our legacy of many thousands of years.

And the textual activism of the Rabbis reminds us that we have the power to face and transform that which is difficult in our texts, in our lives, and in our culture.

And this? is truly sacred.

🌱 Like this? Get more:

Life is a Sacred Text is a reader-supported publication.

To get new posts and to support the labor that enables this project to exist, become a free or paid subscriber. New posts Free every Monday, and paid subscribers get even more text and provocation, every Thursday.

And please know that if you want into the Thursday conversations but paying isn’t on the menu for you right now, we’ve got you. Just email lifeisasacredtext@gmail.com for a hookup.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so here.

Please share this post:

💖 Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💖

TW: ANTISEMITIC GARBAGE (no, I will not be explaining why these are antisemitic. Ask a friend to explain, I will not have the life force available for that.) "An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth" is sufficient for a primitive level of justice when we are struggling through the wilderness dimension of our human adventure. If we are to continue to grow into a full expression of the Power of God, however, we must embrace a new perspective.“ Extra points for use of colonialist terminology! “The Pharisees misunderstood the law in another way.” Those JEWS, always missing the point about what matters. “By encouraging vindictiveness, those religious leaders distorted the intent of God’s Law.” Jehovah’s Witness really bringing the Evil Jew stereotype. And rounding off today’s survey (so much more out there, Google is happy to attest) are the Messianics (yes, they’re Christian) “Yeshua corrected that error. He urged His disciples to be an entirely different breed of people. His message to them was, “Do not press charges. Do not litigate. Do not demand your rights. Do not demand your fair measure or pound of flesh.” 10/10 for the sincere Shylock reference, that’s an impressive accomplishment on Antisemitism Bingo, not one you see every day. ↩

It’s supersessionist, implying of course that there is a new and improved version, that Judaism’s been knocked out in favor of the New Better Thing. (Or, worse, that Jewish sacred text somehow predicts Christianity. It does not.) Respecting Judaism as an independent religious tradition means honoring the fact that, for us, there is only one Bible, and we are a whole complete world unto ourselves. Nothing supplanted. So: call it the Hebrew Bible, please. And while we’re at it, Jews these days generally refer to what’s usually known as the New Testament as the Christian Bible. For the same reasons. Thanks for hearing. ↩

No, really, read the story at the link if you don’t know about the Hatfields and the McCoys. ↩

Prof. Shaye Cohen’s The Beginning of Jewishness is a great book on the move from Judean—”an ethnic-geographic term, like ‘Egyptian,’ ‘Syrian,’ ‘Cappadocian.’”—to Jew, “anyone who venerates the God of the Temple in Jerusalem and observes [God’s] laws.” ↩