Fat Torah: Every Body Beloved

A Guest Post by Rabbi Dr. Minna Bromberg

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

An announcement before today's intellectual main course:

It's been a difficult year, individually, and communally.

Logistically and, especially, morally.

We don't spend enough time talking about the moral toll, and the moral implications. Join us for a conversation about everything we're holding, and what it means:

The next House of Study Zoom Salon will be September 7th, 2pm ET/11am PT.

Join us!!

What does our individual spiritual work look like this year-- for the mundane, the crucial but hard work looking at who and how we have been as individuals-- as well as communities and as a larger society? These are days that require brave moral engagement, but we are up for the task. Join us for a lively, interactive conversation on questions that matter.

Onward!

I have enjoyed and appreciated Rabbi Dr. Minna Bromberg's work long before she began Fat Torah, but this project– centered on educating and inspiring towards fat liberation through the lens of Jewish spirituality– is particularly important.

It's profoundly revolutionary to celebrate every body of every size a culture that wants to encourage so many to be less. And Rabbi Bromberg has opened up a unique and critical lens to the holy, while also facing down some of the specific mishegaas (uh, foolishness) in our community.

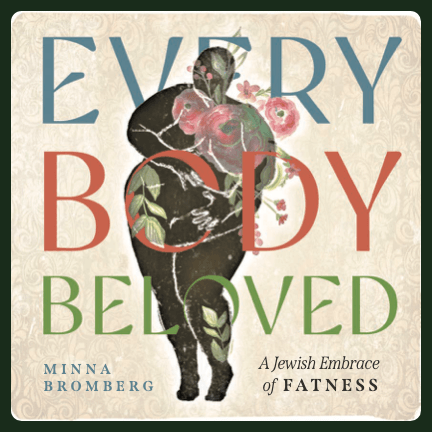

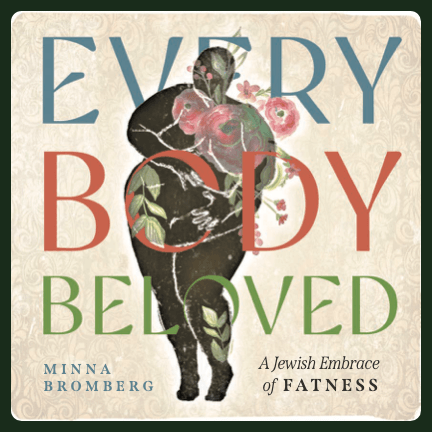

And now, lucky everybody, Rabbi Dr. Bromberg has a book, called Every Body Beloved: A Jewish Embrace of Fatness. You should get your copy with a quickness.

And we have a little preview of it here today!!

Taking Good Care

by Rabbi Dr. Minna Bromberg

(Excerpted and condensed from Every Body Beloved by Rabbi Dr. Minna Bromberg)

When I started more publicly asserting that fat people too are created in the image of God, I knew that one milestone in measuring the reach of this message would be the arrival of “concern trolling”—attacks in the guise of caring about well-being.

When the trolls arrived, they were in fine form. In response to a lovely article about Fat Torah and other efforts at faith-based fat activism, one commenter wrote, “There is never a reason to celebrate being overweight,” while another made it even clearer that hers was a “nonjudgmental” concern: “Not to judge people on the basis of size or weight . . . but let’s not celebrate unhealthy behavior.”

When it comes to fat people, suddenly everyone is a crusading public health advocate using the language of “caring” to do anything but that. Caring is in the eyes, and the heart, of the cared for. In the more than four decades that loved ones, healthcare providers, and complete strangers have expressed concern about my fatness using some variation on the question “But what about your health?” I have not once experienced this concern as caring. To be told I am being cared for when I feel that the opposite is true is gaslighting, pure and simple.

True Caring

The first hint that offers of concern for fat people’s health are not actually caring—whether they come from people who actually know us or from random strangers on the internet—is that they are usually offered without our consent.

A series of stories in Talmud (BT Berakhot 5b) is often used to discuss the topics of suffering, caring, and receiving care.

We read first of Rabbi Yoḥanan, a famed healer, visiting his sick student. (Rabbi Yoḥanan was also famous for being very fat and very beautiful, but that’s another story.)

In our story, Rabbi Yoḥanan begins by asking his ailing pupil,

Is your suffering dear to you? Do you desire to be ill and afflicted? Rabbi Ḥiyya said to him: I welcome neither this suffering nor [any] reward, [that I might receive in this world or the next as a result of it]. Rabbi Yoḥanan said to him: Give me your hand. Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Abba gave him his hand, and Rabbi Yoḥanan stood him up and restored him to health.

Similarly, Rabbi Yoḥanan fell ill. Rabbi Ḥanina entered to visit him, and said to him: Is your suffering dear to you? Rabbi Yoḥanan said to him: I welcome neither this suffering nor its reward. Rabbi Ḥanina said to him: Give me your hand. He gave him his hand, and Rabbi Ḥanina stood him up and restored him to health.

The Talmud asks: Why did Rabbi Yoḥanan wait for Rabbi Ḥanina to restore him to health, if he was a healer?... The Talmud answers, they say: A prisoner cannot generally free themself from prison.

When this text is taught, the emphasis is often put on its moving message of interdependence. Even the most powerful healer needs to be cared for in order to heal. But what strikes me when I think of how much concern is expressed about fat people’s health is the very first question that the healing visitor asks in each story:

“Are your sufferings welcome to you?” In other words, “May I offer you help?” Every one of us needs helping hands at many different points in our lives, but true concern—and helping and healing—starts with consent.

Additionally, true caring means meeting people where they are and addressing their concerns, not only your own. Even if you are an actual health expert, you cannot accurately assess a person’s health just by looking at their fat body. When people tell me they are concerned about my health without knowing what my own health concerns, or lack thereof, might be, they are not truly seeing me.

In one Ḥassidic tale, a rabbi learns something about true caring when he sees two men drinking together.The first asks his drinking buddy,

“Do you love me?”

“Of course, I love you so so much!” replies his inebriated companion.

“No,” the first one insists, “you cannot possibly love me because you don’t know what hurts me.”

When you are concerned about my health without knowing anything about my health, about what does or does not “hurt me,” I do not experience it as caring.

Is “Being Healthy” a Mitzvah?

When the trolling started, I began to notice that some comments came from people who expressed specifically Jewish concerns about fat people’s health. Often these commenters would swap out “But what about your health?” for “But what about shmirat hanefesh?” If this is the first time you have heard of the mitzvah of shmirat hanefesh, please know that I had never heard of this Jewish religious obligation either. Sometimes being a rabbi feels like one long moment of being made aware of all the things you didn’t learn in rabbinical school.

Shmirat hanefesh, which means “taking care of yourself,” is a mitzvah that uses a verse from Deuteronomy as its prooftext. “V’nishmartem me’od l’nafshotekhem,” the verse begins, urging us to “Take very good care of yourselves” (Deuteronomy 4:15). It is worth noting that the meaning of the word nefesh changes over time. In biblical Hebrew, nefesh means a living being—human or animal; biblical Hebrew makes no distinction between body and soul, nor does it explicitly imbue human beings with a “self.” Under the influence of Greek philosophy, Rrabbinic Judaism does begin developing an idea of body and soul as potentially separate “parts” of one human being, but this never coalesces into a doctrinal or fixed definition of what the soul is or how the body/soul/self relationship needs to be construed. In this context, nefesh comes to be used as one of a number of words for the soul/spirit/lifeforce—each with its own nuanced set of meanings—in the Jewish mystical and spiritual traditions.

This potential interpretive openness in various times and places, along with the ongoing presence of the biblical text itself, can allow for varied meanings of the opening words of our verse in Deuteronomy.

More broadly, how each of us sees the relationships between our bodies and any other aspects of ourselves can impact what we think it means to “take care of yourself.”

Health is not an achievement, moral or otherwise, and illness is not a failure.

Similarly, “being healthy” cannot possibly be a mitzvah since mitzvot are all actions that we are called upon either to “get up and do” or to “sit down and refrain from doing.

Mitzvot matter to me, though I see them as something I take upon myself as a devotional practice rather than viewing them as a legal code that I will somehow be punished for violating. So if someone tells me that pursuing health is a “positive commandment” (i.e., one of the “get up and do it” mitzvot), I take that seriously. The question of “what about shmirat hanefesh?” made me curious to know more about this mitzvah.

Was my call for fat people to be recognized as human beings somehow in conflict with shmirat hanefesh, as some online commenters and direct message correspondents claimed?

Healthism, but in Hebrew

In contemporary usage, if my concern trolls and Google were to be believed, shmirat hanefesh is mostly used to put a Jewish patina on plain old anti-fat bias and healthism. Coined by economist Robert Crawford in his 1980 article “Healthism and the Medicalization of Everyday Life,” healthism is “the preoccupation with personal health as a primary—often the primary—focus for the definition and achievement of well-being; a goal which is to be attained primarily through the modification of life styles.” Crawford’s concern is that healthism ignores social determinants of health and necessarily limits the pursuit of health to people with the wealth to do so. In addition to anti-fat bias, we can also think about how racism, ableism, misogyny, ageism, and other oppressive structures make healthism worse.

In popular usage, shmirat hanefesh is used to sell all kinds of contemporary ideas about wellness and fitness (think Jewish-themed juice cleanses). This is not to say that shmirat hanefesh is always used nefariously. It has been used to promote vaccination among the ḥaredi (ultraorthodox) population as well as to encourage mask wearing during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this principle is too easily wedded to racist, classist, anti-fat, and anti-femme diet culture and wellness culture. Indeed, whenever the pursuit of health slides over into non-evidence-based territory—not to mention outright quackery—shmirat hanefesh is right there to wrap up ableism and healthism in halakhic (Jewish legal) bows.

Idolatry

Frustrated by the various takes we were finding on just what shmirat hanefesh was all about, my chevruta (study partner) and I decided to have another look at the verse in Deuteronomy. And when we look at the whole of Deuteronomy 4:15 and its continuation in the following verse, the Torah does not disappoint.

V’nishmartem me’od l’nafshotekhem. “Take very good care of yourselves,”

our verse urges, and why?

“Since you saw no shape when God spoke to you at Horeb out of the fire, lest you act wickedly and make for yourselves a sculptured image in any likeness whatever: the form of a man or a woman.” (Deuteronomy 4:15-16)

What a retort from the text itself! This is a verse about idolatry, specifically about not idolizing a particular shape (or size) of the human body. Taking care of ourselves means making sure we are not forgetting that we ourselves stood at Sinai and heard God urging us to have no other gods but the One.

Ramban, the thirteenth-century scholar and mystic, comments on this verse that it is warning against worshiping only one aspect of God as if God’s Oneness were separable.

We can use our verse as prooftext to help us understand that healthism, anti-fat bias, and diet culture are the very idolatry that we are being warned against; they hold up a particular ideal of body size and health itself as worthy of worship and cause us to forget our inherent human wholeness. Created in the image of the Divine, each of us is a mirror, in this world, of Divine wholeness.

This warning against idolatry can be powerful no matter what we believe, or don’t believe, about God—even for atheists. We have a human tendency to be worshipful, to give power over our lives to nonrational things. If we cannot stop ourselves from bowing down to one thing or another, we ought to at least be intentional about what our objects of worship are. Shmirat hanefesh warns us to make sure we are not worshiping physical health or a narrow definition of what constitutes an acceptable body size as an idol.

I am not being dismissive of the body and its needs and ailments. This is not a “you are not your body” argument. We are allowed to want to live long lives free of physical suffering, and we are allowed to take steps in pursuit of that. We run into trouble when we think our health is entirely up to us and when we mistake a narrow definition of physical health for the whole shebang.

One way that our tradition hints at its preference for something beyond physical health is in the liturgical practice of praying for a refuah shleima, a full healing, even when someone is at death’s door. We do this not because we expect miracles or at least not only because a miracle would be nice once in a while. We pray for complete healing even when physical cure is out of the question because the true healing we seek, the true caring we can offer ourselves and one another, is the reminder of every body’s inherent wholeness.

🌱

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable. ❤️ 🌱

When you sign up for the House of Study, you get deep dives every Thursday, Ask the Rabbi Q & As, montly Zoom Salons IRL, access to over 4 years of archives, a study partner if you want one, and so much more-- and you DON'T have to get more email if you don't want! Don't you deserve all this nourishment and support??

As always, if you want in on the House of Study, but paying isn't for you right now, email support @ lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

Especially without Substack's built-in network, word-of-mouth– forwarding emails, sharing on social media, etc– matters more than ever.

Please spread the word about this post and Life is a Sacred Text in general.

Thank you. 🙏 ❤️

The next House of Study Zoom Salon will be September 7th, 2pm ET/11am PT.

Join us!!

What does our individual spiritual work look like this year-- for the mundane, the crucial but hard work looking at who and how we have been as individuals-- as well as communities and as a larger society? These are days that require brave moral engagement, but we are up for the task. Join us for a lively, interactive conversation on questions that matter.

As always, if you want in on the House of Study, but paying isn't for you right now, email support @ lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

Rabbi Dr. Minna Bromberg brings her uniquely powerful voice—both literally and figuratively—to the urgent work of body liberation within a Jewish context. She is passionate about writing, teaching, and change-making at the nexus of social justice and spiritual care. In 2020, she founded Fat Torah with a clear and compelling mission: to shatter the idolatry of weight stigma and harness the profound resources of Jewish tradition to build a world that embraces all bodies. A gifted singer with five acclaimed albums, Minna also shares her gift by teaching others to lift their voices in song and prayer. Her own unique insights are enriched by her doctoral work in sociology (Northwestern University, 2005) and rabbinic ordination (Hebrew College, 2010). Jerusalem is home, where she lives with her family, continuing to amplify her message of liberation and acceptance.

Get your copy of Every Body Beloved now! (Get a copy for the people in your life – the rabbis, educators, and others who need to read it, too.)