so much to mourn

facing Lamentations' sexual violence

Trigger warning: Sexual assault and abuse, misogyny.

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

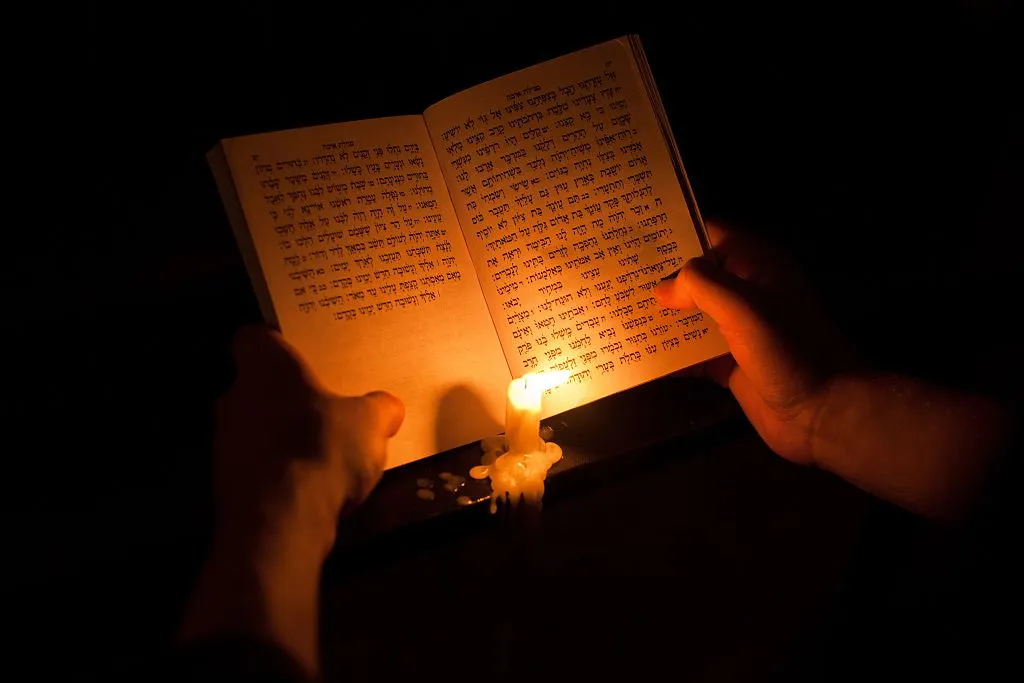

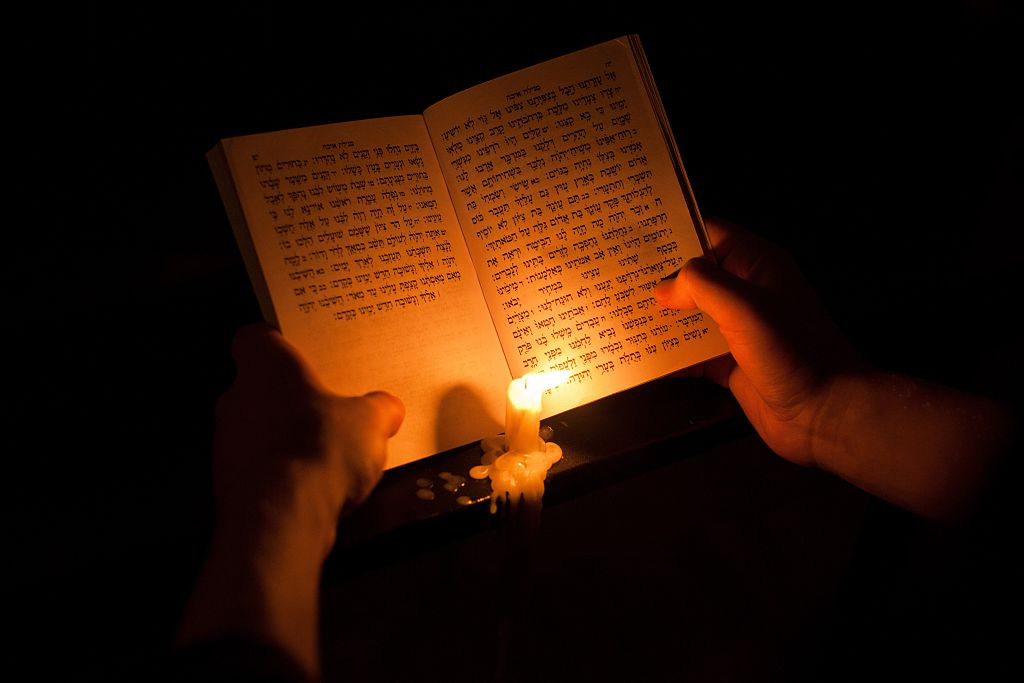

Tisha B’Av, the day marking the destruction of the First Temple by the Babylonians, the Second Temple by the Romans, the First Crusade1, the expulsion of Jews from England2 and Spain3 and many other tragedies that have befallen the Jewish people, begins Wednesday night. It is a day of sadness and mourning, marked in a number of ways, including by fasting and reading the Book of Lamentations.

It’s called Tisha B’Av because it’s the 9th day (תשע/ teysha is the number nine in Hebrew) of the Jewish calendar’s month of Av. (the prefix ב/B’ means “of.”)

(If you’re Jewish and observing Tisha B’Av, but fasting isn’t conducive to your physical or mental health, your health comes first. Check out the great folks at A Mitzvah to Eat for resources, perspectives and other ways to plug in spiritually on fast days.)

The Book of Lamentations is a series of poetic elegies about the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586 BCE. It describes the miseries befallen the Jewish people as the city is laid to waste—death, starvation, and the horrors of war—as well as theological explanations for the disasters and hope for the possibility of being renewed “as the days of old”.

It belongs in the genre of “city laments” that existed in the Ancient Near East; the Lament for Sumer and Ur; the Lament for Ur; and Lament for Uneg/Uruk were Sumerian poems written all probably when Ur fell to Elamites, around 2000 BCE; the Lament for Nippur is also Sumerian, but dates to the Old Babylonian Empire, ca 1900-1600 BCE.

We typically read Lamentations with a somber mood and tone.

But there’s a way that the text is painful that we do not discuss often enough.

It matters that there is so much sexual assault imagery in Lamentations, most notably in the metaphoric form on the imagined body of Zion.

It is brutal.

We meet her in the aftermath of everything that has happened:

Bitterly she [the city] weeps in the night,

Her cheek wet with tears.

There is none to comfort her

Of all her friends.

All her allies have betrayed her;

They have become her foes.

Judah has gone into exile

Because of misery and harsh oppression;

When she settled among the nations,

She found no rest;

All her pursuers overtook her

In the mitzarim/narrow places4 (Lamentations 1:2-3)

The text picks a word that is used sometimes for “suffering,” but in the context of the assaults by Dina and King David’s daughter Tamar, takes on a clear other context:

All the precious things she had

In the days of old

Jerusalem recalled

In her days of sexual assault and wandering5

When her people fell by enemy hands

With none to help her;

When enemies looked on and gloated

Over her downfall.

And there is victim blaming. For example (Lamentations 7-10):

Jerusalem has sinned, therefore she has become a wanderer; all those who honored her demean her, for they have seen her nakedness, and she groaned and turned back. Her tumah clings to her skirts.

(Tumah, as you may remember, is the “everyday state” that can be contracted when coming into contact with various things. The implication that what’s being described as regular, healthy menstruation here seems very unlikely to me. “They have seen her ervah,” her private parts, if you will. It is much more likely that this tumah refers to the aftermath of assault.

She has sunk appallingly, With none to comfort her.— See, God, my misery; How the enemy jeers!

Like, it’s not subtle.

The foe has laid hands

On everything dear to her.

She has seen her Sanctuary

Invaded by nations

Which You have denied admission

Into Your community. (Lamentations 1:10)

I struggle with this every year.

Lamentations can certainly be understood as what the Christian feminist Bible scholar Phyllis Trible would refer to as a “text of terror”—one that portrays horrors and injustices done to women uncritically, in which misogyny is either normalized and/or unchallenged.

And yet, at the same time, I think that we can also choose to find in it the experience of mourning and catharsis that Lamentations is meant to offer.

I believe that both of these things are possible, quite potentially even at the same time.

That is, instead of allowing sexual violence to be seen as the mechanism or core metaphor for of our collective Jewish grief over the Destruction of the Temple and the subsequent exile, we can use Tisha B’Av as a space to mourn so much of what has been taken.

Not just what has been taken in sexual violence, but obviously that.

But also what has been taken in the victim-blaming, the gaslighting.

And in the unspoken but entirely pervasive expectation that abuse victims/survivors should have no problem going to erev Tisha B’Av services every year without being triggered—

that is, re-traumatized through the descriptions of rape and framing of that rape as the victims’ responsibility.

We must mourn all the things that contribute to rape culture. And the fact that this would ever have been a plausible metaphor to use. The fact that our culture, despite progress, still has so far to go, still isn’t truly safe.

Needless to say, dear cherished victim/survivors, please take care of yourself.

And taking care of yourself might even including skipping the Wednesday night reading of Lamentations if that's what you need to do. Let that be OK.

Or, go, but bring whatever you need to Tisha B’Av to keep yourself safe and whole.

Dr. Koach Baruch Frazier, who is not long for rabbinic ordination, on spiritual resilience through the practice of lament and how to use it on our journey to liberation.

But for everyone else, I wonder if we need more of an active intention around the fact of the sexual violence in this text.

For so many people, pretending it's not there doesn't work.

Trying not to be distracted by the hair-curling misogyny, the harm and abuse as we mourn doesn't work.

Let's name it, mourn this too.

We need to. Or some of us do, anyway. And if you're one of the people for whom this is true, I suppose this is an invitation.

(Eli Tzion is a traditional kinnah, song of lament, sung at Tisha B’Av, that depicts Jerusalem as a suffering, grieving woman.)

Could we use the reading of Lamentations to be the chance to try to empathetically enter into, or to at least see, the space where all that pain is kept, to let ourselves feel it and let it absolutely crumble us—destroy our walls—

so that we come out of those five short chapters more open, more feeling?

Could we use it as a time to mourn not just the disasters that have befallen the Jewish people so many times, but the concrete disaster of sexual violence as part of that?

Both at the hands of the Babylonians, but also—in line with the way we mourn on this day—the Roman siege, pogroms, the Holocaust, and so many more places where horrific sexual violence was part of our oppression, subjugation, exile? (TW on all those links.)

Because first of all, sexual abuse was part of all of these horrors.

Can we be willing to mourn sexual violence perpetrated by other Jews? This kinah, song of lamentation, by a survivor of child sexual abuse, may be one place to start.

This pain and trauma is real and brutal, and has been part of our story of suffering since we had a story of suffering.

As Rabba Dr. Melanie Landau writes:

This Tisha B’Av, instead of fighting against the images of female humiliation and victimhood, I am inviting myself and others to enter into the pain that these texts evoke for us, and in fact use them as an opportunity to explore our own lived experience of this breach…and to allow ourselves to be with it inside our own bodies and experience. This includes allowing ourselves to grieve and mourn it, and then to let that mourning connect us back up to the destruction of Jerusalem.

Let the pain in.

It is there. We can't heal as individuals or as a society when we pretend that it's not there.

And if this is a chance to tap into the suffering of the world, let us name the ways in which that still manifests now. Today. Here.

We can regard the text of Lamentations as a chance to bear witness to the harm caused, to hear the voices of victim-survivors telling the truth about their experiences.

We can hear the voices of pain in this text as a protest, as a demand for a better world.

And paradoxically, the formula of the lament can help us to do this.

Dr. Koach Baruch Frazier teaches,

After you have experienced tragedy after tragedy after tragedy, it becomes difficult to stop and mourn. But you see, lament, it has a formula, as I have learned it. And formulas can be useful in times of crisis and uncertainty. This is the gift of our ancestors, giving us the spiritual technology to help us stay on this road of resilience and healing….

The first element of this formula of lament is address: Dear Universe, the Source of all Life, Whoever is out there, Whatever is out there!

The second is expressing your distress. Why in the world are my siblings, my trans women of color, continuing to be killed? Why?

The third: This is where you stop, and you remember that there was a point in time before now, where there was destruction or death, or there was tragedy and it was in front of you. And somehow, some way, you made it through, and now it’s behind you and you’re still here. Part of lament is remembering you’re still here — that you can make it through.

The fourth element is the plea. This is what’s going to make it so I can start healing. This is what I need to repair the harm that was done to me. This is what I need.

The fifth element is gratitude. Maybe it’s gratitude knowing that one day, you’ll be on the other side of this one, too. Maybe it’s gratitude knowing that you used to be on the front end of something and now you’re on the back end. It may be gratitude for allowing yourself, giving yourself the gift of being in your grief, and allowing your body and your soul and your mind to experience it, so you can get on the other side of it.

Let us name all of the pain in this text, and in our history, and our world today and mourn and grieve this and then on the 10th of Av we can come together to create a different kind of future for all of us.

In “Every Truth Spoken Is a Step Toward the Promised Land,” Alex Carter writes,

When we speak the truth to power – saying, this is who we are

We reach back to help those still stifled in Mitzrayim/the narrow place6, or poisedUncertain at the shore.

And still we sing, remembering what we have accomplished,

Committing to the work that remains.

We reach forward to create a promised land

For all created in the image of the Eternal.

The Book of Lamentations (almost) ends:

Take us back, O God, to Yourself,

And let us come back;

Renew our days as of old!

Let us create a world in which our days are renewed.

In which we are all able to take another step closer to home.

🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week. 🌱

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, that's how you can get tools for deeper transformation, a community for doing the work, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕

The First Crusade began officially on Aug 15, 1096 CE (Hebrew date: 24th of Av, the year 4856), slaughtering at least 10,000 Jews in its first month in pogroms and destroying Jewish communities in France and the Rhineland. ↩

Jews were expelled from England on July 18, 1290 CE (Hebrew Date; the 9th of Av, year 5050). ↩

The Jews were expelled from Spain on July 31st, 1492 (Hebrew date: 7th of Av, the year 5252). Can’t make this stuff up. ↩

Tzar, narrow, forms the root of the word Mitzrayim, Egypt, the place of Jews’ enlavement in the Hebrew Bible. ↩

Dr. Susannah Larry writes, ”An issue regarding the translation of הנע is that it refers to a larger category of social shame than merely sexual violence, although here, I think its translation as “rape” is mandated…. For example, took(“ַָוִיַּ֥קּח ֹאָ֛תהּ ַוִיּ ְשׁ הֶֽנַּעְיַו הָּ֖תֹא בַ֥כּ Shechem prince Hivite the ,)2 .v (Dinah of story 34 .Gen the in her and laid with her and ענה her”) Contrast this occurrence of הנע with the story of Tamar and Amnon in 2 Sam 13. Tamar makes her voice clearly heard before the rape even begins, protesting in 2 Sam 13:12, חאָ־לאִַי֙ ־לאַ תְּעַנֵּ֔נִי”) No, my brother, do not rape me!”). As Sandie Gravett notes, this is the only explicit female refusal of sex in the Hebrew Bible, which points to the overall lack of an ancient concept of female sexual agency. Amnon refuses to listen:וְלֹא אָבָה לִשְׁמֹעַ בְּקוֹלָהּ וַיֶּחֱזַק מִמֶּנָּה וַיְעַנֶּהָ וַיִּשְׁכַּב אֹתָהּ׃—’But he would not listen to her; he raped her and lay with her.” ↩

Egypt. Because the Hebrew word for narrow is tzar, Mitzrayim is also understood as "narrowness," as in, the narrow and confining places in life from which one emerges physically and spiritually. See the echo of Lamentations 1:3. ↩