Some Notes On Anger

Just In Case That Ever Might Be Useful

Hey, all!

First of all, apologies that I didn’t get a newsletter out last Sunday. Between two short weeks marking the end of Jewish Holiday Season and my ON REPENTANCE AND REPAIR trip to Atlanta (which was fabulous, fabulous) I just wasn’t able to get something up and loaded before we all turned into Shmini Atzeret/Simchat Torah pumpkins, and then suddenly the week was half over.

But! Now your Life is a Sacred Text chariot awaits you!

So. Today we’ll be talking about anger. Whoo!

Anger.

There are a lot of reasons to be angry these days. Abortion rights have been destroyed. Trans lives are still under attack. The 5th circuit declared DACA illegitimate for everyone but those already enrolled. The Supreme Court is taking up a terrifying new slate of cases that could upend the Indian Child Welfare Act, narrow the government’s power to protect the nation’s waterways and ban discrimination against LGBTQIA+ people, finish decimating the Voting Rights Act and federal election oversight. And injustices of every kind continue on as they always have.

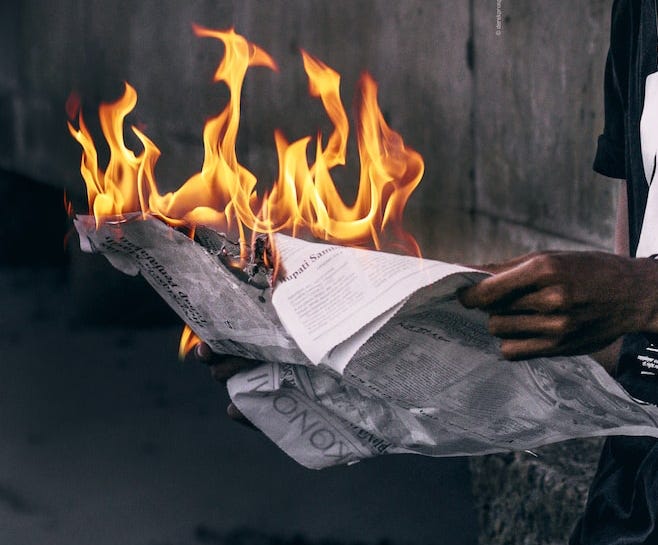

We need to be careful. As Rabbi David Rosenn observes,

“there’s a reason that the symbol of anger is fire—mastered, it has tremendous productive energy; left to burn out of control, it can destroy everything in its path.”

On the one hand, anger has been the fuel for individuals, communities and movements to fight for change many times throughout history. But on the other hand, well, it’s kindled and fomented the kind of hate that targets the vulnerable at least as many times over.

How can we feel and express anger without falling prey to the same destructive forces that are consuming those who preach hate?

We think, often, of anger as a prophetic characteristic—Isaiah or Jeremiah furiously chastising the selfish, neglectful people Israel again and again. And yet, the Talmud teaches,

“Whoever becomes angry--if wise, his wisdom leaves; if a prophet, prophecy leaves.”

So anger—or, at least, certain kinds of anger—can hamper our ability to speak truth to power. And Midrash Proverbs puts it even more succinctly:

“Anyone who is short-tempered in judgment will in the end forget what he has to say.”

Indeed, living and acting from a place of triggered fury eventually takes its toll on multiple fronts.

It can make us more reactive and less strategic; it can make us less able to see clearly or unable to hear useful nuance; it can burn us out and add stress to our relationships. We’ve all too often seen (or been) a well-meaning person torn to pieces online for an innocent misstep or a divergent perspective, witnessed (or experienced) potentially productive conversations shut down with would-be allies, and noticed (or been, uh, rather inside) a rigidity of thinking that comes from being—to put it bluntly—pissed off.

And yet, the Mishnah, another important collection of early rabbinic writings, understands that getting mad is an understandable reaction to injustice, whether personal or societal. For, (Mishnah Sanhedrin 10:6),

“As long as evil people exist in the world, fierce anger exists in the world; once the evil ones are removed from the world, fierce anger will be removed from the world.”

Anger is a fact of life. It’s going to be around as long as injustice is.

And the fact of the matter is, anger serves a number of valuable roles as a response to evil: It shows us where our boundaries are; it gives us a forceful response to a injustice; it moves us to action; it helps us understand where our limits are. A primal scream can be a release that helps us exorcise the hard feelings so that we can move forward in catharsis. If evil is a disease, anger serves as the white blood cells who rush to our body’s defense—a healthy evolutionary response to a legitimate threat.

So how can we engage anger usefully in our lives, and in work for social change? What’s the difference between righteous indignation and, well, the less helpful self-righteous kind?

One way of thinking about whether or not anger is productive might have to do with how it’s used. As Rabbi Rosenn would say—whether or not it’s mastered.

The 11th c. philosopher Solomon ibn Gabriol asserts that

“anger is a reprehensible quality—but when employed to correct or to reprove, or because of indignation at the performance of transgressions, it becomes laudable.”

In other words, if you use anger to help people to improve, to protest injustice—it’s a perfectly fine thing.

The trick—and this is a serious trick indeed—is to get awfully clear on whether or not that moment of anger can give us the bravery to say what must be said or whether it clouds our judgment about the message.

That discernment is trickier than it sometimes feels in the moment—I, for one, have caused some of my most problematic public harm when I have felt like I am correcting and reproving in a moment of righteous indignation—but my fury, and my neglecting to take a moment to breathe and check myself, caused me to cross the line into uncalled-for personal attacks.

Needless to say, sometimes we’re more effective in our efforts to “correct and reprove” when we’re not already boiling over.

Another teaching attributed to the 18th c. mystical master the Baal Shem Tov suggests that there’s a way to transform anger in vital ways. For, he says,

“When tempted by anger… overpower your baser inclinations and transform that trait into a chariot for God.”

In other words, anger can take us—or we can take anger—to a few different places. It’s all too easy to tap into our less evolved traits when we’re emotional—our greed, pettiness, selfishness, our craving. Anger can all too easily turn into vindictiveness—the part of us that wants revenge, that won’t be satisfied until we burn it all down.

But, the Baal Shem Tov suggests, that’s not the only way. We can turn our fury into a “chariot for God,” a vehicle to serve the good and the holy. Then, our anger isn’t about responding from fear or quenching our wounded ego, but, rather, pushing for a more just world—one with more space for everybody.

This is the anger that fuels productive action.

This is the anger that helps people feel seen, validated—less alone.

This is the anger that serves as a call to arms, that summons people into the work that must be done.

This might be the difference between that fury that sizzles on the surface of our consciousness and an anger that comes from someplace deeper.

Surface-level anger can make us seething and impulsive, destructive, while that more rooted anger can continue to fuel us for the sometimes difficult long haul.

In order to let the anger of our “baser inclinations” burn off, we need to pause and catch our breath.

The 13th century Persian Sufi poet Rumi once famously likened being a person to being a guest house. Emotions show up as "unexpected visitor[s]," and, Rumi implores us, we should

"Welcome and entertain them all!

Even if they are a crowd of sorrows, who violently sweep your house empty of its furniture, still, treat each guest honorably.

They may be clearing you out

for some new delight.”

That is, when a feeling shows up, we should give it some space to do its thing. Rather than trying to push our anger aside, we should allow it in, and acknowledge it, knowing that even our most intrusive of fury will clear us out for new insight, if we welcome it with compassion and trust that it can be a useful teacher.

Which isn’t to say that we act on it right away.

Sometimes it’s OK to feel the anger.

To breathe into it.

To let it sizzle.

To let the impulsivity burn off and to look with curiosity at what might be underneath.

This isn’t to say that, once we’ve paused to catch our breath, we won’t be angry, or that our anger won’t motivate us to work for good. Rather, we will be driving our responses to injustice, rather the other way around.

And then our work for change will be a very holy chariot indeed.