Who Leads Us Across the Sea

Who Sings, Who is Said to Have Sung

This is Life as a Sacred Text, an expansive, loving, everybody-celebrating, nobody-diminished, justice-centered voyage into one of the world’s most ancient and holy books. We’re working our way through Exodus these days. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here.

Sometimes there’s a story behind the story.

Sometimes leadership is hidden, sometimes it’s buried, twinned, sometimes there’s more to it than we might see.

The Israelites flee. Pharaoh has yet another change of heart about his decision to to let his labor force go after all, and sends his army to pursue them.

The Israelites make it to the precipice of the Red Sea, trapped by water on one side and the encroaching army on the other.

And then the waters part; the Israelites are ushered through to freedom, and they sing.

They see the Egyptians pursuing them into the sea; they see the sea closing only after the Israelites are safely on the other side, while the army intent on re-enslaving them drowns.

The Song of the Sea—Exodus 15—is widely understood to be one of the most ancient texts in the Torah; the language used there is generally considered by scholars to come from a period that predates much other Biblical literature.

And the Song was likely changed, somewhere along the way.

Exodus 15 opens thusly:

Then Moses and the Israelites sang this song to God. They said: I will sing to God, for God has triumphed gloriously; Horse and driver God has hurled into the sea. God is my strength and might; God is become my deliverance. This is my God and I will enshrine God; The God of my ancestor, and I will exalt God. (Exodus 15:1-2)

The next seventeen verses tell of the Egyptians drowning in what we call in Hebrew the Sea of Reeds, words of praise for God’s might, the terror of other nations in the face of God’s power, and the guiding of God’s people to

“Your own mountain, The place You made to dwell in, God, the sanctuary… which Your hands established.”(Exodus 15:17).

It closes with, “God shall reign forever and ever.”

But then Exodus 15:20-21 comes in with a curious coda:

Then Miriam the prophet, Aaron’s sister, took a timbrel in her hand, and all the women went out after her in dance with timbrels.

And Miriam chanted for them: Sing to God, for God has triumphed gloriously; horse and driver God has hurled into the sea.

That language is familiar, isn’t it? In fact, it feels so familiar that it almost doesn’t belong there. What happens if we remove the introductory verse about Moses and the Israelites, and move Miriam to the top? Suddenly we have a powerful call-and-response:

Then Miriam the prophet, Aaron’s sister, took a timbrel in her hand, and all the women went out after her in dance with timbrels.

And Miriam chanted for them: Sing to the God, for God has triumphed gloriously; horse and driver God has hurled into the sea.

They said: I will sing to God, for God has triumphed gloriously; horse and driver God has hurled into the sea.

In fact, this is what many scholars suggest may have happened. It seems that the Song—perhaps first existing as part of an oral tradition—may originally have been ascribed to Miriam, who led the Israelites in a powerful call-and-response of praise and worship—and that she may have later been cut and pasted out of the top of the Song to give Moses a more prominent role.

Movements do this. It’s entirely possible, probable, even, that Miriam was there, there at the start, even if she was ultimately pasted to the end of the Song as a post-script. Because it suited another agenda to center Moses.

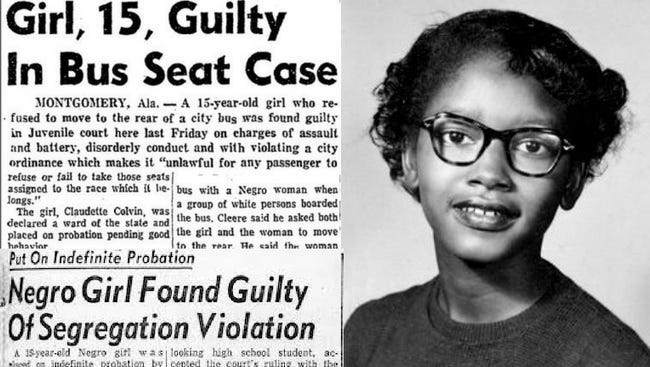

I’m drawn to think about Claudette Colvin and Rosa Parks here, for some reason.

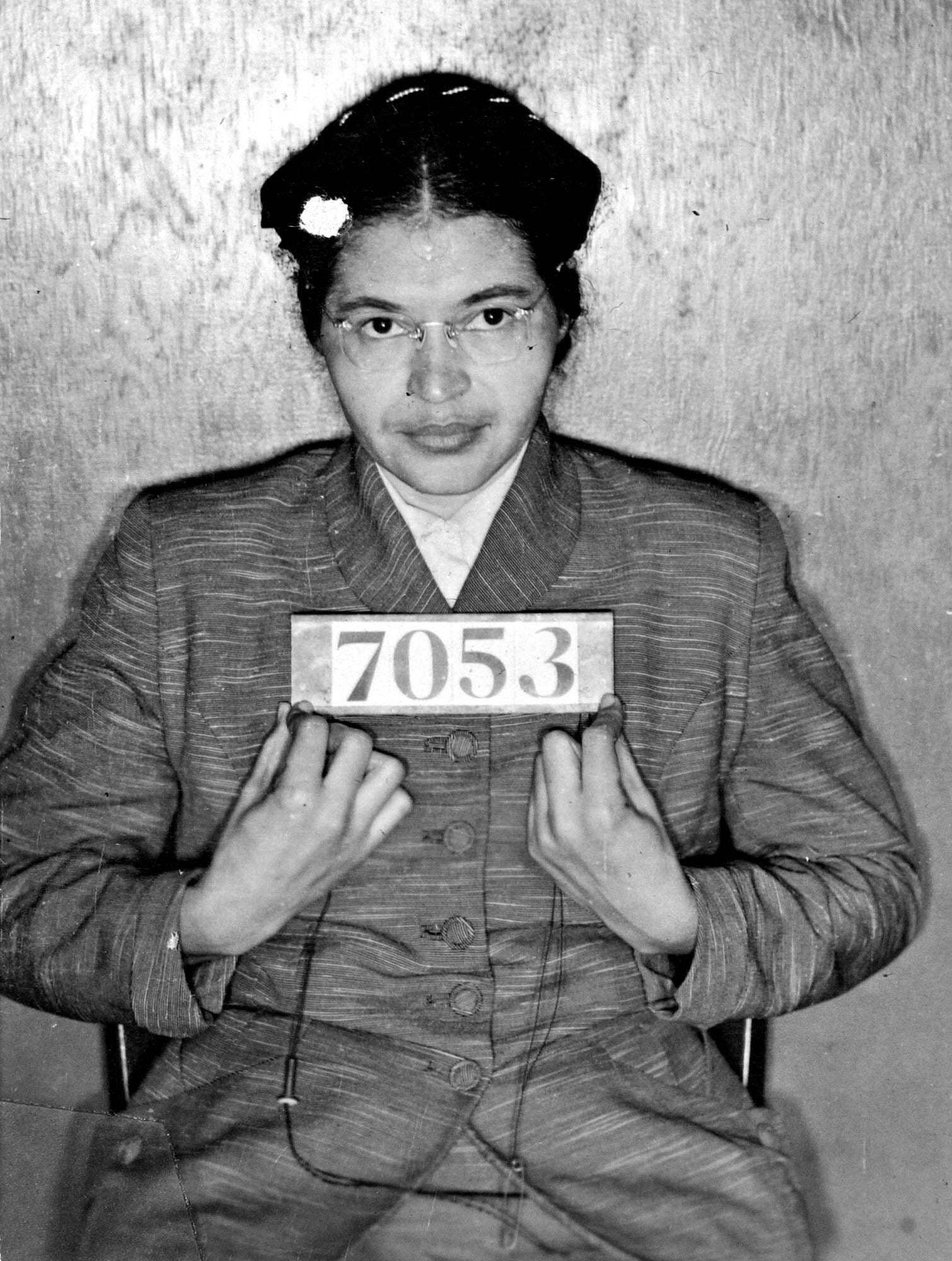

Most people know of Rosa Parks—the woman whose arrest in December 1955 for refusing to cede her seat to a white passenger famously kicked off the Montgomery Bus Boycott. But she wasn’t the first.

In March of that same year—nine months before Parks’ arrest—a 15-year-old Black teenager named Claudette Colvin did the same thing. She was on a bus with some friends that day, and the driver asked several of them to get up so that a white woman could sit. But, as Colvin recounts,

“History had me glued to the seat. Harriet Tubman’s hands were pushing down on one shoulder and Sojourner Truth’s hands were pushing down on the other shoulder.”

She was dragged off the bus and thrown into an adult jail. Several other Black people arrested before Colvin had also been arrested for refusing to give up their seats, but she was the first to ask to retain a lawyer, to try to fight back.

The local chapter of the NAACP arranged representation for her and initially thought hers could be a great case to challenge bus segregation, but the leadership team changed their plan upon learning that she was pregnant.

There were two extremely practical concerns—that conservative churches wouldn’t rally behind an “unwed mother,” and that without the churches, there would be no boycott; and that the white media would have a field day with the optics and use it to discount the movement entirely. (This might be the case, still, today—and remember, this was the Jim Crow South in 1955.)

Rosa Parks first met Colvin about two weeks after the teenager’s arrest, and was in touch with her regularly, as Parks was then the secretary of the local NAACP branch. Colvin’s arrest indeed inspired her own actions.

(For those who don’t know, Rosa Parks was not a tired old woman who could not get up—she was a strategic, 42-year-old organizer who was deeply involved in the movement work on this very issue. As it happens, her civil disobedience was spontaneous, but connected less to fatigue than to her recognition of the bus driver—a notoriously abusive man with whom she had already had a negative encounter. As she put it, “the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”)

Parks was well-known and respected in her community, and her arrest served as the trigger for the bus boycott. By the evening of the day that Parks took her famous stand, the Women’s Political Council had circulated a flyer calling for a boycott, and a strategy meeting was held the very next morning. She became a galvanizing force, and eventually an icon, both because of the relationships she had in the community, and because, in part, of the optics. Parks was older, and Christian, and her arrest would certainly tell a simpler story to the newspapers. As Colvin’s biographer, Philip Hoose, put it,

“They worried they couldn’t win with [Colvin]… Words like ‘mouthy,’ ‘emotional’ and ‘feisty’ were used to describe her,” whereas Parks was regarded as “stolid, calm, unflappable.”

Notably, Colvin was one of the plaintiffs in Browder v. Gayle, the case whose ruling ultimately brought the boycott to an end.

Colvin was there. She was there the whole time.

But, for too long, she remained a footnote in history.

Why was Miriam brought to the bottom of the Song?

We’ll never know for sure why Moses was deemed a more appropriate figurehead at this critical moment, but we can guess.

Many scholars have. Did enhancing Moses’ leadership help bolster the political power of those who claimed him in particular? Was the advent of the monarchy a triggering event for centralizing patriarchal authority? Did this editorial move take place during a shift away from an earlier, more household-based system in which women held more authoritative roles? Is the work that Miriam did in the liminal period of Exodus—the time between enslavement and establishing the new norms of freedom—something that later power structures could not abide? Is there some other reason?

We don’t know, and we may never know.

But we can see how Miriam, here, was stripped of the credit due her leadership, though notably the text nonetheless retains acknowledgement of her as a prophet.

She was there. She sang. She led.

Miriam brought the people through the complex waters to their new life.

The story of the Exodus, as we have seen, begins with birth—the birth of the Israelite babies that pose a threat, the midwives Shifra and Puah who risk their lives to bring this people into being, the birth of Moses who will grow up to liberate his people, and Yocheved’s, Miriam’s and Pharoah’s daughter’s protective safeguarding of this infant.

In fact, of the five women who help to begin the process of liberation at the beginning of Exodus, Miriam is the only one who carries them through the rest of the story—from the pains of oppression into the waters of freedom, through the Israelites’ forty years of wandering in the desert.

She was there.

The Hebrew word for Egypt is Mitzrayim, from the root tzar, narrow. I’m not the first person to observe that the Exodus is a birth itself, one that involves passing through the narrow place—beginning with blood, the blood on the lintels and the doorposts that kickstart the birth-pangs of this deliverance, through the parted waters, into a new life, the birth of the Israelites as a people, as a nation.

Miriam the prophet and the women took their timbrels and sang, danced as the Israelites got to dry ground.

They were the midwives of liberation.

As the people of Israel, the Jewish people were being born, Miriam and her attendants were present, encouraging, celebrating. Helping to bring the people into the world. And this birth is joyful—full of music, dancing, songs of praise, as the journey towards liberation can sometimes be.

Claudette Colvin and Rosa Parks were midwives to a movement as well.

May we all honor the leaders who lead, even if they aren't recognized by official channels, or history books, in all the same ways.

May we find ways to change what the official channels teach.

May we all cross out through the narrow place and find freedom.

May we work to help everyone through the narrow place into freedom, as well.

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week.

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And you can get even more as part of a community of rabble rousers going deep into the questions and issues, with even more text and provocation, every Thursday.

And please know that nobody will ever be kept out due to lack of funds. Just email lifeisasacredtext@gmail.com for a hookup.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so here.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post:

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way.