What one line in the Yom Kippur liturgy teaches us about transforming society

Plus: Survey results!

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

I've been meaning to do a little post-survey check in, so I'll do that, and then I've got a vort (little word) on a little part of the Yom Kippur liturgy, since that exquisitely holy day begins already (!) Weds evening.

So, first: Things I learned from the survey:

1) Y'all are nerds, just like me. (OK, I knew that. Y'all are the best.) 🫶

2) Based on your interests, after we finish! the whole! Torah! we'll work our way through the rest of the Bible, but will intersperse it with other things: investigations of the Talmud, mysticism, history, how-tos, personal essays, hot button issues and other things related to life now, weird theories, guest posts, and whatever else comes down the pike.

3) Some folks wanted to know if you can try House of Study for free, and I want to remind you that YOU CAN! Now all the House of Study tiers are set with a built in trial period now.

And if you're in it to support Life is a Sacred Text because we literally (actually) cannot keep going without you– truly, this is literally as independent media as it gets–but the House of Study tier is a bit steep for you, there's now a lower support tier in there as well:

Now, specifically for my non-Jewish readers:

Friends! You are explicitly welcome here!

So maybe a few words on why I'm committed to writing for the intelligent reader of every background: What my work seeks to offer Jews of every background and type, I hope, is obvious. Anyway, here's a screed against gatekeeping, and here's another one on what I think the point of Torah is.

And I believe that some of the beauty in my tradition can impact everyone, just as my reading Julian of Norwich, ʿ'Attar of Nishapur and Suzuki Roshi (among others) were key at various points on my long, weird, winding path.

To clarify: I don't believe in the buffet model of spiritual practice (aka: Oh, here's a Jewy thing that I can do and an Indigenous practice that I can appropriate that seems cool, even though neither of those things are home base and I don't have a lot of cultural knowledge or context...!) Which is to say, I think you should have a spiritual path that is your path and do that thing only (but, notably, investigating conversion and diping your toe into the possible waters of Jewish practice is not the same as stealing someone's stuff!)

But I do believe that we should all read widely, and learn broadly. It only makes us wiser and more capable of understanding ourselves, our culture, and (if relevant) our own sacred texts, in a more thoughtful way. Whether you're here for the history or because this stuff is just interesting to you or because you feel that it makes you a better Unitarian or Catholic or Muslim or Wiccan or whatever, as long as you take in what you're learning in a respectful way, there's no downside. So feel at home, yes? OK? OK!

Now.

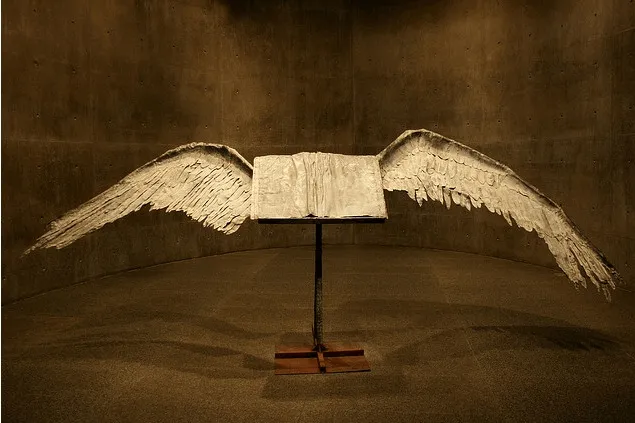

As Yom Kippur begins–with the very start of the Kol Nidre service, we find the following lines:

With the consent of the divine, and consent of this congregation, in a convocation of the Heavenly court, and a convocation of the lower court, we hereby grant permission to pray with transgressors.

This line is first found in the margin of 13th century Machzor (High Holy Day prayerbook) manuscripts, evidently originated by my maybe (?)-ancestor, Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg (d. 1293),* so that there was no doubt that even those who had been subject to herem, excommunication, could and should show up on Yom Kippur– was building off of the following bit of Talmud:

*Is there any real connection? Were our families just from / kicked out of the same German town? Who knows. I tend to claim him when I agree with his opinions and observe that there's no way to know if there's a family connection when I think his opinions are terrible, as one does. 🤷♀️Rav Ḥana bar Bizna says that Rabbi Shimon Ḥasida says: Any fast that does not include the participation of some of the sinners of the Jewish people is not a fast.... Abaye says that this is derived from here: “It is God Who builds God's upper chambers in the heavens and has established God's bundle on the earth” (Amos 9:6), i.e., when the people are united as a bundle, including their sinners, they are established upon the earth. (Talmud Kritot 6b)

And possibly this, too:

When God explained to Joshua the reason for the Jewish people’s defeat at the city of Ai, God said: “[the people of] Israel sinned” (Joshua 7:11). Rabbi Abba bar Zavda says: From here it may be inferred that even when the Jewish people sinned, they are still called “Israel.” Rabbi Abba says: This is in accordance with the adage that people say: Even when a myrtle is found among thorns, its name is myrtle and people call it myrtle.(Talmud Sanhedrin 44a)

What's the underlying principle? We can't have a fully functioning, fully holy society if we throw people away, lock them away forever for making a mistake.

As happens so often in our culture– particularly now.

This does not mean that we tolerate harmful, abusive, unrepentant behavior as acceptable, give people who cause harm positions of power, or reward them for tripling down unrepentantly. There are many mechanisms for holding people accountable in a functioning culture, many ways that we can, together, say: "Not these privileges, not this access, and these boundaries, here, until it's clear most especially to those you've harmed, or to people they designate, that you're safe and have done an appropriate amount of reckoning and amends work."

But that doesn't mean we have to say that you can never find a way for those who have made mistakes to come into our spaces and worship together with us, or that– say– one stops being a Jew even if one causes harm (even in the name of Judaism, ahem).

And this principle – you're one of us even when you've sinned, and we can't even convene our holiest day of the year if we're keeping harmdoers out– reminds me of some of the alternatives to carceral punishment that I see around.

For, as law professor Daniel J.H. Greenwood writes,

“The restorative justice foci on mutual dignity, on censuring crime rather than criminals, on inclusiveness and empowerment, all seem fully in keeping with the older insights of the Jewish law tradition: even a sinner is a member of the community. And criminals (or potential criminals) who are treated as members of the community are more likely to accept that they are members of the community and therefore more likely to act like members of the community.”

Or as Judge Joseph Flies-Away, former chief judge for the Hualapai Tribal Court, puts it, in his community, when a person commits a criminal act,

“People say, ‘He acts like he has no relatives.’... People do the worst things when they have no ties to people. Tribal court systems are a tool to make people connected again.”

How to get from where we are now– a world with so, so much pain and harm and oppression– to something like this?

One of the things that I appreciate about Mariame Kaba’s work in general, including against the prison industrial complex, is that she often names the fact that she doesn’t know how to solve every conceivable issue within her vision of a just world. And that demanding better than we have now doesn't mean that we have to know everything before we start. It might be a process. It might take some time to figure some of the hardest parts out. But that doesn’t mean that we can’t do better, starting today. As she puts it,

“None of us has all of the answers, or we would have ended oppression already. But if we keep building the world we want, trying new things, and learning from our mistakes, new possibilities emerge.”

But I believe that it begins with principles like the granting of permission to pray with transgressors. (After all, on some level, even if we didn't get the full Spinoza treatment, we're all harmdoers, just as we have all been harmed, are all bystanders to harm.) Reminding us all what Rebbe Nahman of Breslov teaches:

If you believe you can damage,

believe you can fix.

If you believe you can harm,

believe you can heal.

May we all be sealed for safety and care this year;

for love, for support;

for healing ourselves and one another; for holding ourselves and each other accountable through necessary transformation and repair.

May we all be sealed into building the world that we want to see, iteration by iteration, through trial and error, as our vision for what can be comes into being.

May we all be sealed for holy connection.

G'mar chatima tova– may you, may all of us, be sealed for good.

🌱

A reminder about the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable. ❤️ 🌱

When you sign up for the House of Study, you get deep dives every Thursday, Ask the Rabbi Q & As, montly Zoom Salons IRL, access to over 4 years of archives, a study partner if you want one, and so much more-- and you DON'T have to get more email if you don't want! Don't you deserve all this nourishment and support??

As always, if you want in on the House of Study, but paying isn't for you right now, email support @ lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

Especially without Substack's built-in network, word-of-mouth– forwarding emails, sharing on social media, etc– matters more than ever.

Please spread the word about this post and Life is a Sacred Text in general.

Thank you. 🙏 ❤️

Support independent Torah and the commitment to telling inconvenient truths:

A couple on Yom Kippur from the archives:

Sometimes a textual mystery is just proof of Torah’s narrative genius. Or: How the story of Aaron performing the Yom Kippur ritual fits in not only the topical but emotional structure of the Torah.

This reading of the Jonah story -- read Yom Kippur afternoon, addressing themes of repentance and return-- through a neurodivergent lens by the brilliant Rabbanit Dr. Liz Shayne is more urgent and needed than ever now.