Bad Indians and Narrative Seeds

two book excerpts to transform how you encounter stories

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

I wish you all a day of great gratitude, no matter where you are.

Today feels like an apt time for something that I've wanted to share out for a while, now–

That is, it's my great honor to share excerpts from two very important books that make a great cocktail– get them both and read them in conversation with one another, and with everything else you read.

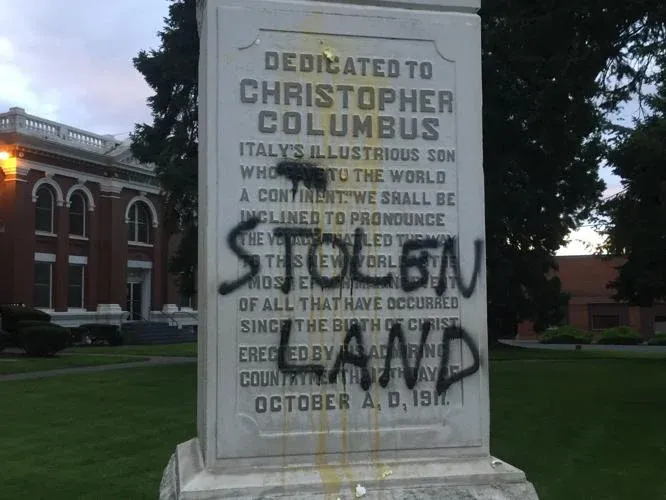

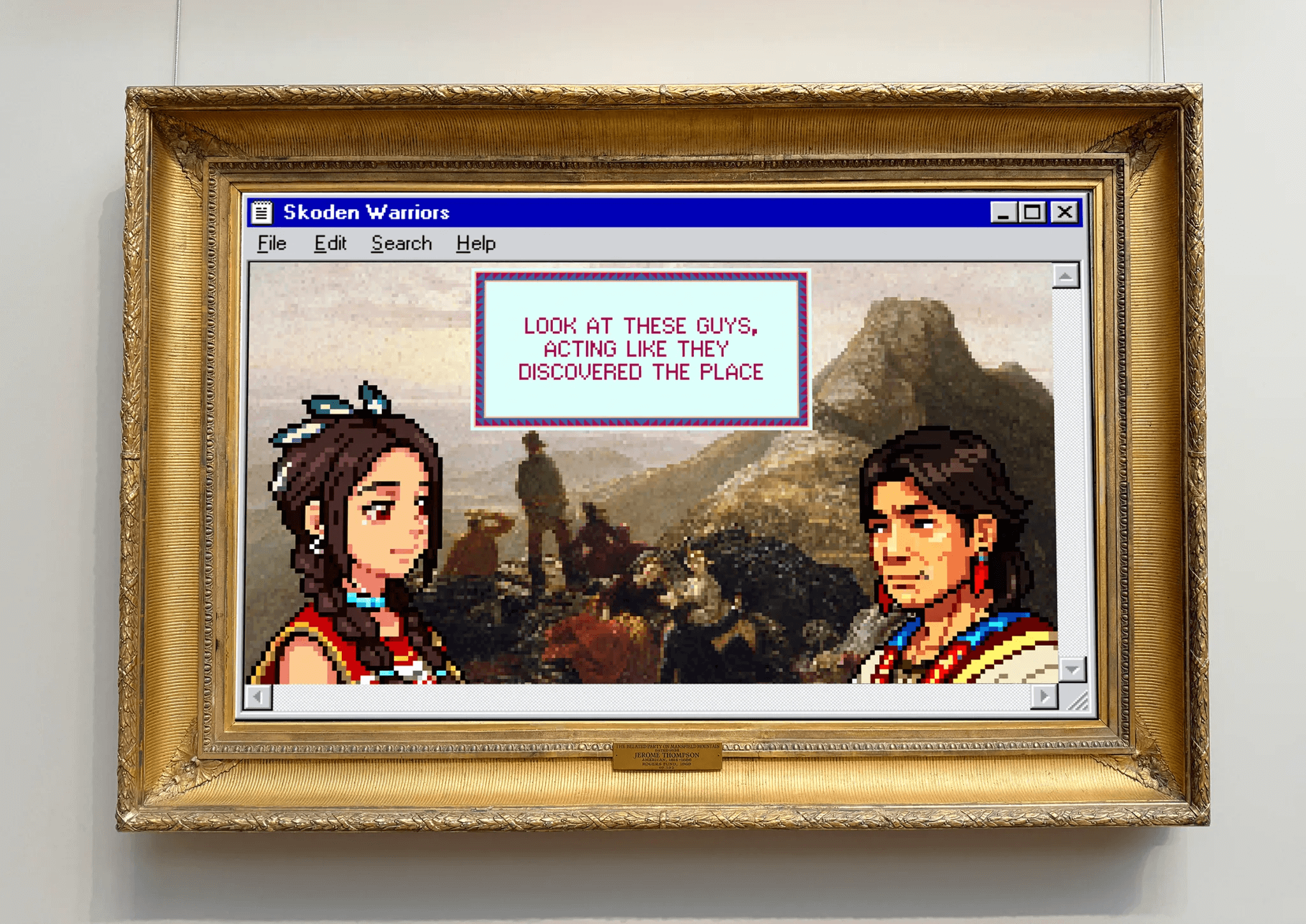

Narrative choices are everything. They certainly underlie the myths surrounding the holiday celebrated today in the U.S., as well as the larger stories around the colonialist harms preceding and following that time–

so this seemed like a perfect day to learn from two brilliant Indigenous women who have lessons that are both critically specific and applicable to everything we do here at Life is a Sacred Text ... and beyond.

If you let them, they will transform how you experience reading, stories, and the life informed by both of these things (which is to say: everything.)

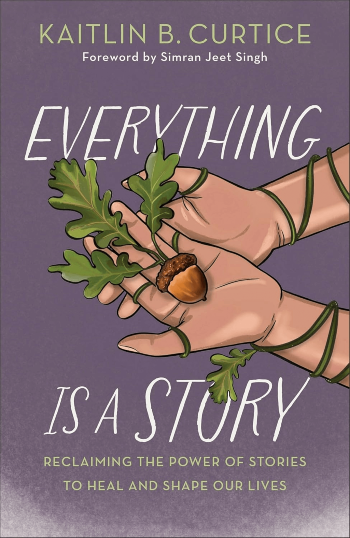

We'll start with Everything is a Story: Reclaiming the Power of Stories to Heal and Shape Our Lives

by the Potawatomi poet, author and theologian Kaitlin B. Curtice:

We may be storytellers, but we are always inheriting stories— from Segmekwe (Mother Earth), from the trees and the waters, the ants and the coneflowers, and, yes, of course, the oak trees....

The world also shifts with a story’s birth, with a story’s beginning....

Is any story completely new and unique? Our birth stories as humans are unique to a point, but we are still human. Acorns fall to the ground and go on their own journey, but they are still acorns. So, what makes a story magical? I’d say it’s the journey that a story takes—who the story encounters, how they are shaped, and where they end up.

We are told so many stories throughout our lives, stories in childhood and as adults, stories as we age into the last stages of these human-body lives.

We are told stories about creation, about life and death, about family, about friends and enemies, about what we should believe.

Sometimes these stories give us room to breathe and grow, and sometimes they suffocate us.

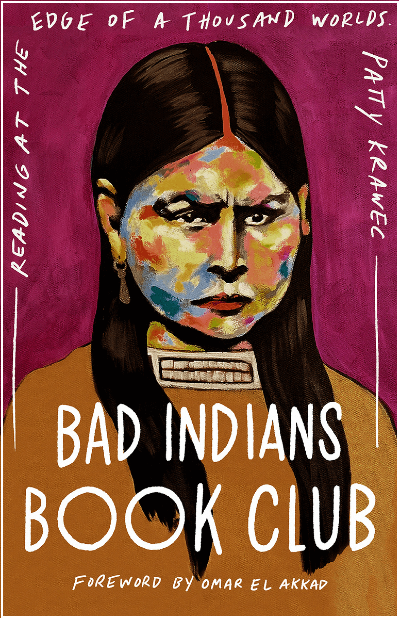

And now we'll move to Bad Indians Book Club: Reading at the Edge of a Thousand Worlds

by the Anishinaabe author and activist Patty Krawec:

In a world that is increasingly polarizing along religious, racial, and ethnic lines, the solidarity that happens when we set aside the political categories meant to keep us apart and talk to each other is becoming critical to our survival.

Reading groups or book clubs have a long history of exploring new ideas: indeed, the power of this kind of collective reading is such that during the years of chattel slavery, Black people were not allowed to read at all. Reading groups proliferated in the 1970s as consciousness raising, and they continue to be sources of grassroots education across a range of racial and political categories.

There is a reason, after all, why more and more people seek to ban the books that point us towards collective liberation.

Bad Indians Book Club emerged from a series of conversations I had with friends and authors, some of which became podcasts, about books read and written. Like happens in any good book club, ideas about how we could live differently emerged from the connections between us: readers and writers from a variety of backgrounds who are no longer seeking inclusion into a house that is on fire.*

*James Baldwin wrote, “Do I really want to be integrated into a burning house?”I write this as the world is awash in protest, people raising hell, as Wente puts it, all of which is being done wrong according to Good Citizens. We’re too loud, too inconvenient, too demanding, too everything. Demanding something other than genocide, violence, and extreme inequity, we’re the bad ones. I’m okay with that—with being one of many Bad Indians who challenge the stories we tell about the society in which we live, because the things we believe have consequences that are often borne by others, consequences we may not see.

My first book, Becoming Kin, challenged the myths and stories that Canada and the United States tell about their history. But history isn't the only story we tell about our encounters with the worlds around us.

This book is an invitation to join me in challenging all the stories.

I hope that you can begin challenging the stories you encounter—stories that, like the colonialism in which they are rooted, serve to displace and erase other ways of knowing.

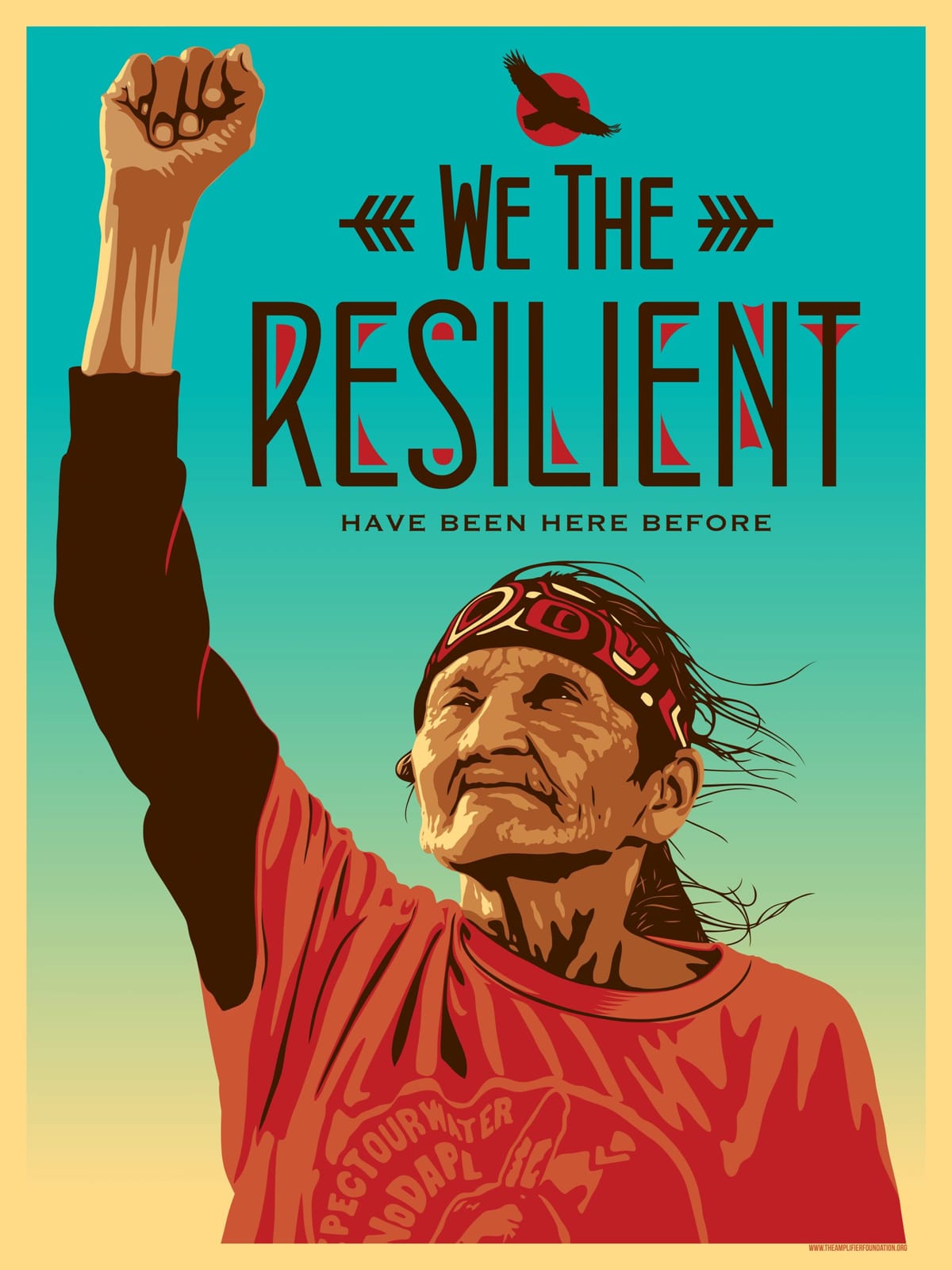

We live in a culture that romanticizes certain kinds of outlaws, and I don’t want to do that, but we should pay attention to how subaltern people are spoken of when we refuse to take our place.

To remind us of what’s at stake, of how we are seen and spoken of when we refuse to behave, memoirist Deborah Miranda writes a “Novena to Bad Indians,” a novena being an urgent nine-day prayer petitioning for grace or favour. She offers gratitude and intention to those who are called names and painted as violent. She petitions those who refused to accept their position in social and gendered hierarchies. She asks for grace from women whose sexual agency and reproductive choices were and are seen as threatening. She honours those who refused to convert to a Christianity that arrived hand in glove with empire and those who later recanted. She writes,

illuminate the dark civilization we endure.

Teach us to love untamed, inspire us to break rules,

remind us of your brutal wisdom learned so dearly:

even dead Indians are never

good enough.

Bad Indians Book Club is a novena, of sorts: nine chapters of public prayer to Bad Indians and those like them who refused to be left in their special interest section.

Bad Indians know that you learn best when you push aside the dust and detritus you have become accustomed to and make room for new ideas and new ways of thinking about things.

Bad Indians take the life around us seriously, even when it is life we don’t understand.

Bad Indians return to themselves through histories told by those who have a different stake in those stories.

We are experts at refusal and creating hostile spaces, and we tell our own stories, even when they aren’t pretty.

Bad Indians wield stories like weapons in the war against imagination.

We pick medicine with the things that go bump in the night, and we know that we have a future despite everything that has been stolen, buried, and burned.

There is something defiant about being a Bad Indian, about leaning into these negative stereotypes. Something adolescent and feral. If I’m going to get into trouble anyway, I might as well deserve it. This book is, ultimately, a book about refusal: refusing political categories and the borders and violence that comes with them, refusing to assimilate by becoming the kind of person the state cannot assimilate. It’s written by a Bad Indian who doesn't just want to survive this current apocalypse.

I want to join with others—Bad Indians and more—to midwife new worlds into being.

Let's end with some words from

Everything is a Story: Reclaiming the Power of Stories to Heal and Shape Our Lives by Kaitlin B. Curtice:

We are not automatically given home. Some of us journey to find it, and home doesn’t always mean the place where we grew up, does it? Many of us are still finding home. When I’m asked where I’m from, I always stumble, because I can’t really answer that. I’ve lived in so many places I feel like a bit of a nomad, and I’ve known people from many places who welcomed me as family, as kin.

A spiritual home, a genealogical home, a physical home— these things take time and examination, just like that tiny acorn we hold.

As we enter into this journey together, as we consider the origins of a story, the very seed we tenderly hold in our hands, we acknowledge what it means to look for home, to journey toward home, to find home, to create home, to sustain home.

Along the way, we go beyond ourselves, asking what it means to be home to others.

May we begin there.

Kaitlin Curtice is an award-winning author, poet-storyteller, and public speaker. As an enrolled citizen of the Potawatomi nation, Kaitlin writes on the intersections of spirituality and identity and how that shifts throughout our lives. She also speaks on these topics to diverse audiences who are interested in truth-telling and healing.

Patty Krawec (Anishinaabe Ukrainian) is author of Becoming Kin and Bad Indians Book Club and cofounder of the Nii’kinaagana Foundation. An activist and former social worker, she belongs to Lac Seul First Nation in Treaty 3 territory and resides in Niagara Falls, Ontario. Krawec has served on the board of the Fort Erie Native Friendship Centre and cohosted the Medicine for the Resistance podcast.

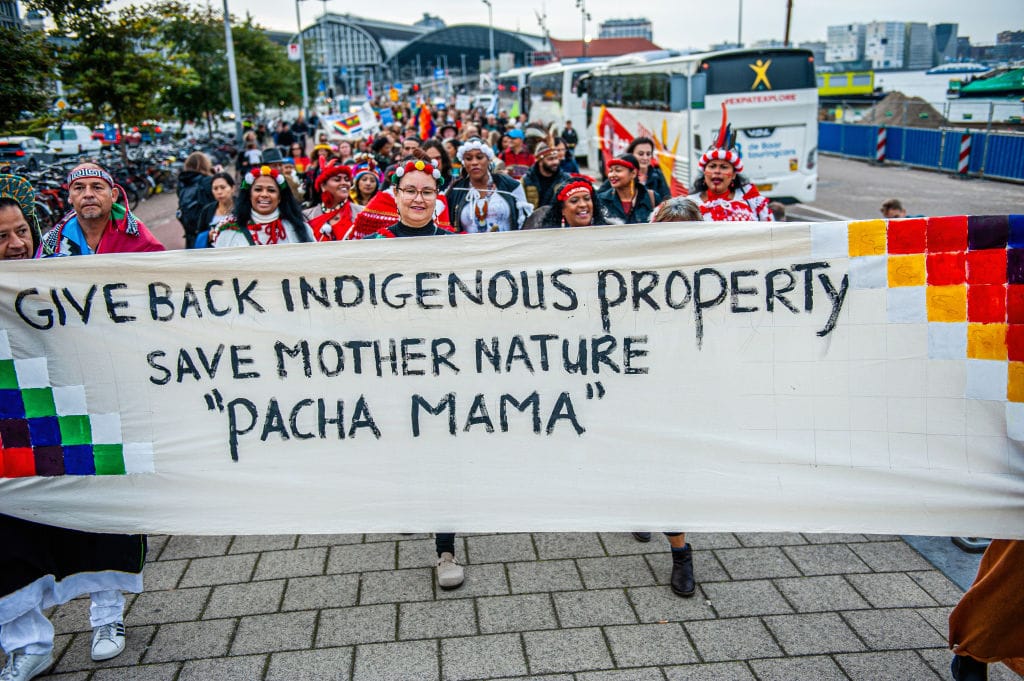

And, of course, remember, #LandBack doesn't mean giving up your home tomorrow, but it does mean supporting Indigenous sovereignty in every possible way, and developing an appropriate relationship with the land on which you live, the people from whom it was stolen, and with others.

Knowing on whose land you dwell is a first step– this is a helpful tool. From there, it's pretty easy to click through to the main tribal websites, for starters. Some communities have programs like Real Rent, or other means of supporting self-empowerment. There are many national orgs, as well, though today especially I'll lift up Patty's work with The Nii’kinaagana Foundation.

Share this post

GIFT A LIFE IS A SACRED TEXT HOUSE OF STUDY SUBSCRIPTION!

NOW 20% off through 2025!!

Weekly injections of nourishing wisdom!

Monthly Zoom Salons!

Four years of archives!

So much more!! ✨

No, but really.

This is your chance to get in on the House of Study:

ALL SUBSCRIPTIONS ARE 20% THROUGH 2025 NOW!!

Weekly goodness to nourish you during these trying times

(But more email is OPTIONAL!

You can just go hard periodically on the website if you'd rather)

Monthly Zoom Salons

Ask the Rabbi Q&As

Access to 4 1/2 + years of archives

Get hooked up with a hevruta/study partner if you want

Supporting the infrastructure that makes this possible

and so much more....

and as ALWAYS, if you want in on the House of Study, but paying isn't for you right now, email support @ lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up. ❤️ 🌱

Support independent work committed to telling inconvenient truths:

And don't forget: When you join the House of Study, you can join

The December Zoom Salon!

Sunday,December 7, 2-3:30 EST, 11-12:30 PST.

(You do not have to know anything to show up!

And you are allowed to keep your screen off the whole time if you want!

You can also choose to have your screen on and be crafting or eating or with your hair a mess and we are all very casual and friendly and welcome you exactly as you are!)

There's been a lot of desecration and devastation this last year, these last years, and knowing how to create holiness, once again, in the wake of so much ruin is essential. In the season of Hanukah, we'll look at a couple of texts that might be able to show us how to reignite and purify that which seems like it has been entirely lost, whether in our polity or in ourselves.

Come get the fuel you need.

RELATED: