Deuteronomy's Liberation Theology

how it can teach us to expand our vision for tomorrow

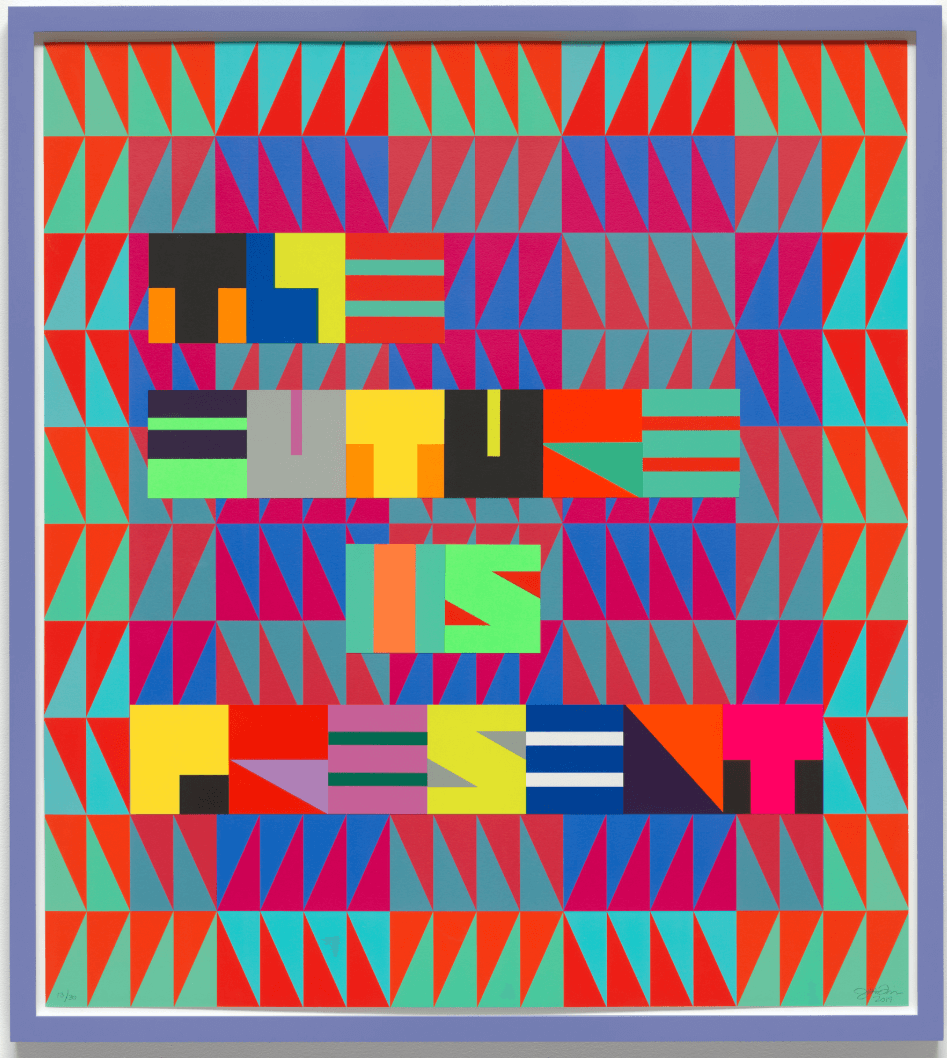

It's time for some Torah on what influences, hampers, and shapes the liberatory imagination.

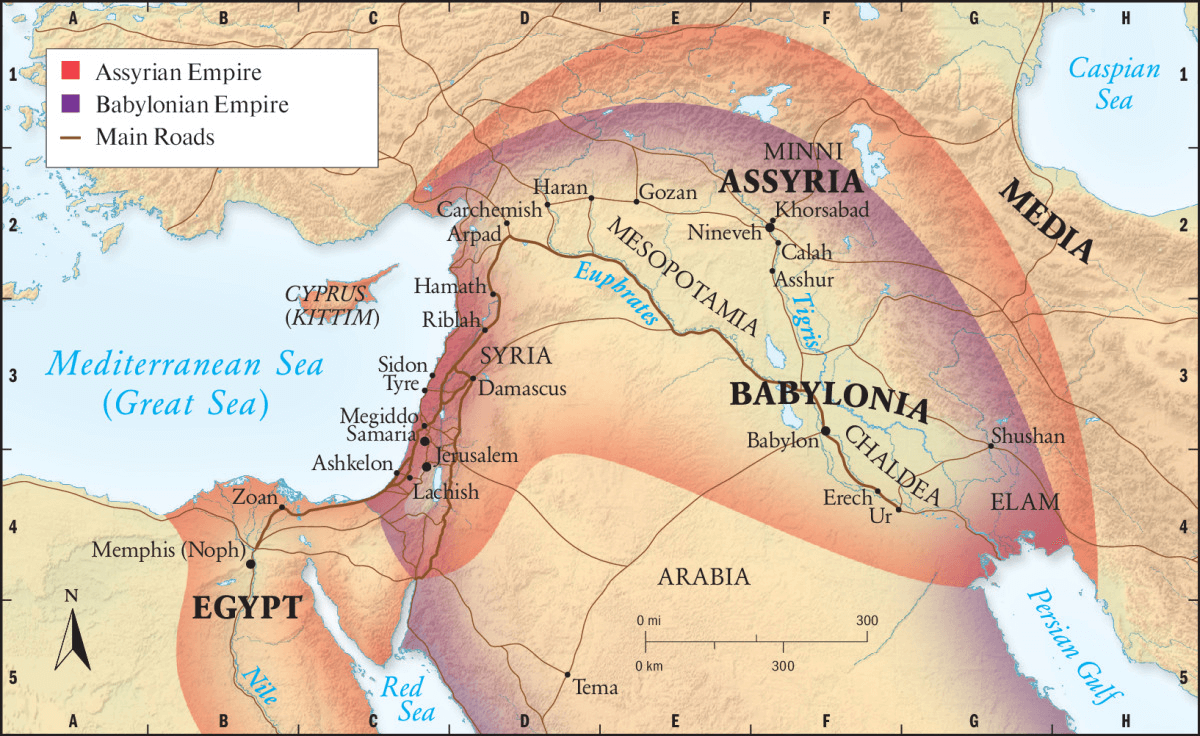

After King Solomon died in 926 BCE, his son Rehoboam ruled poorly, and the united monarchy became two separate states: Judah and Israel.

In 722 BCE, Israel was conquered by the Assyrians. Many people were forcibly relocated—reportedly, ostensibly, the time when 10 "lost" tribes were dispersed—and many Israelite refugees came into Judah, bringing the ideas they'd developed in the north along with them.

At the same time, in 735 BCE, the Assyrians conquered Judah and made it a vassal state of Assyria.

Many scholars have pointed out the similarities between various parts of the Book of Deuteronomy and Assyrian vassal treaties—that is, the agreements that the Assyrian Empire made with its vassal states.

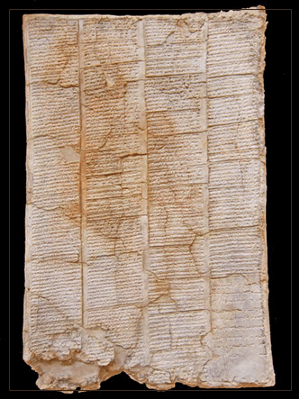

As a reminder, we generally assume that Deuteronomy was connected to the reign of the Judean King Josiah (who reigned c. 640–609 BCE). Recently, a copy of Esarhaddon’s Sucession Treaty (672 BCE)* was found Tell Tayinat, in nearly-Syria, leading scholars to assume that other copies may have made their way into the the region, perhaps into Judea.

*This treaty bound the inhabitants of the Assyrian empire to ensure the succession of Esarhaddon’s son, Aššurbanipal (reigned 668-627 BCE) to to the throne.

L: Esarhaddon, closeup from his victory stele over Egypt in 671 BCE. (Stone carving of the profile of an Assyrian ruler with a conical crown and tightly curled beard, holding a cup and a staff) R: An actual original copy of the actual Succession Treaty regarding the succession of Aššurbanipal, the crown prince of Assyria, imposed by his father, Esarhaddon, the king of Assyria, in 672 BCE. (Image of a carved ancient Near Eastern stone treaty engraved in columns of a light pink/brown stone).

I won't go through all the possible examples, but to give you a sense of things, I'll quote Esarhaddon’s Sucession Treaty in simple italics, and the Torah text in italics with line indent:

You shall neither change nor alter the word of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria but heed this very Assurbanipal, the great crown prince designate.

Everything that I command you, that you are to take care to observe; you are not to add to it, you are not to diminish from it! (Deuteronomy 13:1)

Whoever changes, neglects, violates, or voids the oath of this tablet and transgresses against the father, the lord, and the adê of the great gods and breaks their entire oath....may your name, your seed, and the seed of your brothers and your sons completely disappear from the face of the earth.

Beware that the heart of no man, woman, clan, or tribe among you turns away from God our God today to pursue and serve the gods of those nations... all the curses written in this scroll will fall upon him, and God will obliterate their name from memory. (Deuteronomy 29:18-20)

May all the great[t go]ds of heaven and earth who inhabit the universe and are mentioned by name in this tablet, strike you, look at you in anger, uproot you from among the living... May food and water abandon you; may want and famine, hunger and plague never be removed from you.

God will send upon you disaster, panic, and frustration in everything you attempt to do until you are destroyed and perish quickly, [because you have forsaken me]. ...God will afflict you with consumption, fever, inflammation, with fiery heat and drought, and with blight and mildew; they shall pursue you until you perish. (Deuteronomy 28:20–22)

May Sin, the brightness of heaven and earth, clothe you with leprosy and forbid your entering into the presence of the gods or king. Roam the desert like the wild-ass and the gazelle!

God will strike you with boils of Egypt and with tumors, with scabs, and with itching, from which you cannot be healed; (Deuteronomy 28:27)

May Šamaš, the light of heaven and earth, not judge you justly. May he remove your eyesight. Walk about in darkness!

God will strike you with madness, with blindness, and with confusion of heart. You will feel about at noon like a blind-person feels about in deep-darkness... (Deuteronomy 28:28-29)

May Venus, the brightest of the stars, before your eyes make your wives lie in the lap of your enemy; may your sons not take possession of your house, but a strange enemy divide your goods.

A woman you will betroth, but another man will lie with her, a house you will build, but you will not dwell in it...your donkey will be robbed [from you] in front of you...your sheep will be given to your enemies, with no deliverer for you. Your sons and your daughters will be given to another people, while your eyes look on and languish for them all the day, with no God-power to your hand. (Deuteronomy 28:30-32)

Deuteronomy has a lot of this kind of language: “IF you are good and do all of these things, you will be safe and protected. IF you are not...well, not so much.” When you understand them as subtweets of Assyrian treaties, things become clearer:

We are vassals, absolutely. But not of an earthly kingdom.

The only ruler we serve is God.

The authors of Deuteronomy took the terms of subjugation and subverted them to become the terms of liberation.

✨ Upgrade your Life is a Sacred Text subscription now! ✨

✨Get all the archives! ✨Get all the Thursday text studies and bonus conversations (in your inbox or online!) ✨Join our monthly Zoom Salons! ✨ Support the labor that makes accessible learning happen! ✨

They replaced their service to an earthly king with service to the divine.

Deuteronomy is profoundly subversive in this way.

This is the same message that we saw in Exodus, in a different key: We don't serve Pharaoh, we serve God. We don't serve the Assyrian king, we serve God.

Later, our Rabbinic texts will say, in a thousand ways: We don't serve the Roman emperor, we serve God.

And maybe it's the renunciation of Empire is one of the most enduring religious concepts across time and place.

How to turn chains into wings, the yoke of Assyria into the yoke of Heaven.

In other key ways, Deuteronomy aligns with a vision of Liberation Theology, which focuses on orthopraxy over orthodoxy - that is to say, what a person does is more important than what they believe. As we have seen over these many months, Deuteronomy has taught us that we must pursue justice justly, striving to go beyond the letter of the law, that we must both care for those in need today and fight for systemic solutions for tomorrow, that joy is, in itself, an action focused on the enfranchisement of those most marginalized, that we create sanctuary for those at risk of communal violence, that both personal and systemic redistribution of economic resources is an obligation. As is labor justice, and not only caring for, but loving the non-citizen.

But I also wonder about how Deuteronomy's authors' ideas were limited by the vassal treaty model. What else could freedom have looked like? If there were other possibilities for shaping this future, it's not clear that they saw them.

As such, this story invites us to ask, not only: How can we subvert the terms of our oppression to become the conditions for our own liberation?

But also: In what ways are our liberatory imagination, our own visions of what's possible and should be, limited by the terms of our oppression? We can see from here, maybe, what other ways of thinking the Deuteronomists might have reached for that they couldn't have, from where they were.

What aren't we seeing now, because we're so stuck in our own assumptions about how things are and what's possible? What else do we need in order to create an expansive liberatory imagination, to not be limited by what is known and familiar?

I think about Deuteronomy in contrast to the Exodus story. Some scholars (and there are lots of debates about dating, here) suggest that the Exodus story really became the foundation of our tradition during the Babylonian exile.

The Babylonians defeated the Assyrians/ Egyptians in 605 BCE, then laid siege to Jerusalem. The first deportations from Judea to Babylon started in 597 BCE, and the Temple was destroyed 587 BCE.

If, indeed, the Exodus story either originated or really took root in exile, well– one might understand how that could be the case: It's the story of oppression by a foreign power, about dreams of liberation and hopes for return to the Promised Land.

In this way, it's possible that the Exodus story helped the Judean exiles both address of the pain and suffering of now as well as to articulate an expansive vision of freedom.

That doesn't mean that they created it all from scratch; a linguistic analysis suggests that the Song of the Sea– Exodus 15– is one of the oldest bits of the Torah that we have. This was likely woven in to other parts of the narrative at some point. Imagine using the Song of the Sea to answer the pain of Babylonian captivity.

Imagine how we might use very ancient traditions today to address the suffering of now, to give us doorways and windows out. How could they to help us construct a vision for a more whole tomorrow?

What else do we need to create an expansive liberatory imagination, to not be limited by what is known and familiar? What else can help us see beyond the known and familiar ways of being?

After Babylon then fell to the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE (every empire ends eventually!) the exiled Judeans (not everyone in Judea, but a big chunk of population, especially the elite and trade classes) were permitted to return. The story of the Exodus was codified back in Judea, carried back home.

When people talk about liberation theology, they usually refer to the critically important work of folks like the Peruvian Dominican priest Gustavo Gutiérrez, the Black American theologian James Cone, the Māori priest and scholar Dr Jenny Te Paa Daniel, the Mexican biblical scholar Elsa Támez or the Jesuit priest Jon Sobrino.

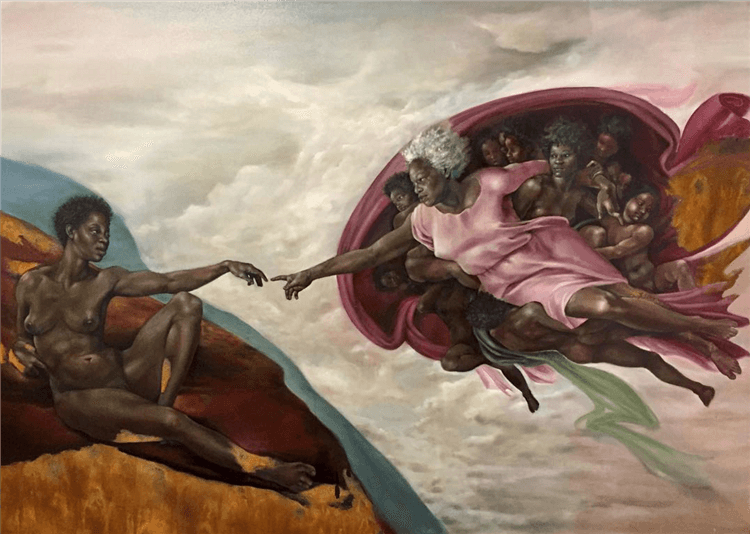

But Exodus was liberation theology from the start—not only the story of liberation, but the story for those who were in need of liberation.

It was always there. There is no neutral mainstream reading.

And Deuteronomy, too, though less well-understood as such, is a liberation text, a radical repurposing of the tools of the oppressor, a redrafting into the terms of freedom.

People try to neuter the radical power of these texts, but they have always been about overthrowing Empire, always been about freedom from oppression.

They have always offered a pathway to our own.

There is no secret other meaning.

A reminder about the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable. ❤️ 🌱

When you sign up for the House of Study, you get deep dives every Thursday, Ask the Rabbi Q & As, monthly Zoom Salons IRL, access to over 4 years of archives, a study partner if you want one, and so much more-- and you DON'T have to get more email if you don't want! Don't you deserve all this nourishment and support??

As always, if you want in on the House of Study, but paying isn't for you right now, email support @ lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

GIFT A LIFE IS A SACRED TEXT HOUSE OF STUDY SUBSCRIPTION!

Weekly injections of nourishing wisdom!

Monthly Zoom Salons!

Four years of archives!

So much more!! ✨

Share this post

Support independent work committed to telling inconvenient truths: