GUEST POST: The Torah I Learned at ACT UP

How Judaism Brought Me Closer To My Father’s Memory as A Second Generation Queer Parent, by Elsa Sjunneson

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

I'm delighted to share this guest post for you today by a dear friend, the eminently badass and delightful Elsa Sjunneson.

We were catching up by text, and she mentioned that she was working on a d’var Torah (sermon) for her local synagogue's Pride Shabbat event on this topic, and– knowing both Elsa’s story and her writing– I begged her to let me run a guest post version.

If you haven’t read her cultural criticism-slash-memoir, I urge you to get on that immediately. Being Seen: One Deafblind Woman's Fight to End Ableism is both powerfully-written memoir and a searing, incisive look at the way disability is portrayed in movies, TV, in books and elsewhere in popular culture. And though the essay below is more on the tender side, her wicked sense of humor is all over Being Seen. (It’s not for nothing that her social media handle is usually SnarkBat.) She’s also a Hugo, Aurora and British Fantasy Award Award-writing author of fiction, writes comics for Marvel, is basically just cooler than all of us. (Combined.)

One note about this piece: It’s personal essay. Among other things, it talks about Sjunneson's relationship with a faith tradition with which she had personal experience. Your experience with that same tradition might be different. Let that be OK. And there are various queer/religious resources at the end of the piece.

Happy Pride, everybody.

Fight hard. Love big.

❤️🧡💛💚💙💜🤎🖤🩷🩵

The Torah I Learned at ACT UP:

How Judaism Brought Me Closer To My Father’s Memory as A Second Generation Queer Parent

by Elsa Sjunneson

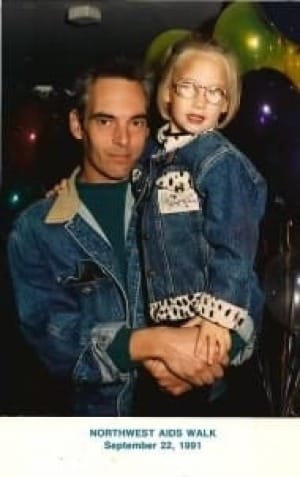

I remember the Pride when I was 7 years old rather vividly. Perhaps it is because it’s an oft-repeated story, perhaps because it was documented, perhaps because I was being the tiny activist that has grown into the adult activist I am now.

However you prefer to categorize this story: As a 7 year old I was featured on what I believe was the front page of the Seattle TImes, handing out condoms during the Pride march down Broadway. My grandmother was horrified. I was proud.

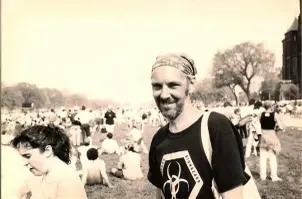

I was there with my father, the ACT UPctivist, the AIDS patient, the gay man who should have lived. I was there because he had been educating the gay community on how to stay safe for as long as I could remember. My dad’s name was Michael, by the way. He was a good dad. Pride was a family thing for us. I remember it as a protest, rather than the wild celebration in downtown Seattle that it has become. I remember the protestors. I remember the hateful words that were spat at us. I remember the sheer unmitigated joy when we reached Volunteer Park and everyone was celebrating together, shedding the words that had been used to harm us by outsiders.

Learning to engage with hate, to live with it, to let it roll off your back is a skill that we all have to learn when we are raised in marginalized communities. It is a skill I often wish I didn’t have.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that march, and about the surrounding environment at Pride that year for a lot of reasons. I remember that people thought it was inappropriate for me to be handing out condoms - but why, when I knew that was one of the main ways to protect my community from the disease that was killing my father? Should I have handed out sharps containers instead? Maybe latex gloves?

The idea that children must be protected from and insulated from queerness is not new. It was happening then, and it’s certainly happening now with 22 states (including my bordering state of Idaho) banning gender affirming care for kids under 18.

I digress, but I knew what was happening to my dad. Just like queer kids now know who they are and what they’re doing. I knew, and I wanted to help keep my community safe.

But apparently, that just wasn’t ok. That was a reason for people who protested our Pride to call my father an unethical f-word.

So I can’t quite say “look how far we’ve come” because in some ways, we haven’t. People still pearl clutch when they see children at Pride. People still believe children must be protected from innate realities that sometimes live right inside of those self-same children.

I knew my dad was dying. I knew my dad was dying from a disease that the government laughed at during press briefings. I knew that when the phone rang, more often than not it was to tell us another one of the beloved community that was raising me had died.

As a second generation queer parent. I’m raising my stepkids 63 years after the riot, 50 years after Seattle’s first Pride protest, in a world that is both better and worse for those of us in the LGBTQIA+ community.

It is better because more of us are out.

More flavors of queerness are acknowledged, more people share their identities without fear. I’m incredibly proud to be a queer stepmother in a time when it is so much easier to find resources to understand who you are, or who you might grow up to be. It’s better because less of us are dying. There are more medicines for people like my dad, who are living longer, and less painful lives.

But I am also raising my stepkids in a much scarier time, in many ways.

Because so many of us are out, and because of that very same education about gender and sexuality from which so many of us benefit, we are more visible. We become targets more readily by those who hate, misunderstand and judge us.

My father was Catholic. For a long time, I thought that I would have to be a Catholic to be close to his memory. But what I realized, after careful study, was that his faith had the unfortunate capacity to push me from his memory, to force me to identify wrongness where I could find nothing wrong, and to believe he was somewhere nasty and unpleasant because of who he was.

Judaism allowed me to be close to him, to remember him fully, and to have my community remember him without exception.

He could be loved because of who he was, not in spite of it.

No one in Jewish community asked me to compromise my father’s rest after a horrific disease because of his sexuality.

No one asked me to apologize for him being gay, or in fact for me being bisexual.

There were no apologies for being exactly who we were, as intended by the divine.

My father was an activist. My father was gay. My father was a drag queen. His blessed memory aligns with the queer woman of faith that I am. A person who believes that all of us are created b'tzelem Elohim, in the divine image.

Queer people are made in the image of G-d.

Disabled people like me are made in the image of G-d.

Sick people like my father are made in the image of G-d.

We are free to celebrate the sparkling rainbow of identity as beautifully, fearfully, and wonderfully made. We are free to see beauty and divinity in all expressions of gender, in all expressions of sexuality, within family structures that suit us.

The way that we as a people interpret holiness and memory means that I can grieve my father in the fullness of his complexity, his whole being rather than piecemeal.

I don’t have to worry about where my father has gone after death. I see a lot of people wrestle with the Christian theologies that say one thing or another about what is the right kind of body, or sexuality, held as full of goodness by their church or their community or their God.

I don’t have to do that. I don’t have to apologize silently or publicly when I say the Mourners Kaddish. I do not carry questions about whether those around me will accept his memory as blessed or holy. I am not asked to carry a burden for him.

That makes me a better parent. That makes me a better human. I don’t need to ask questions about whether or not someone qualifies as being loved by the divine, and I don’t think anyone should be forced to carry that burden.

This kind of faith, this is what tikkun olam–healing the world– looks like.

I don’t think my dad would have been Jewish if he’d had a choice. But I think he would have liked where I ended up on my faith journey. I think he would have liked the fiercely intellectual and accepting brand of theology that I study and practice.

I think he would have liked that I take Heschel’s statement of praying with my feet, and follow in my daddy’s footsteps. I march for causes I believe in. I fight to right inequalities, both in synagogue and outside of it. Through all of that, I am constantly reminded that I do not have to fight the battles my father did in order to practice his faith.

This practice makes me the kind of parent I want to be. I want to be able to model for my children that we all can make the choices we need to for ourselves. That we can be loved for exactly who we are. This practice makes me the kind of person that I want to be: able to see the divine in everyone.

Just the way my father did when he took me to Pride.

May your Pride this year be safe, be proud, and filled with the love of our ancestors, especially the ones who didn’t know how they could be loved, because we can love them even more fiercely now than we could when they lived.

Hugo, Aurora and British Fantasy Award Award winner Elsa Sjunneson writes and edits speculative fiction and nonfiction and writes comics for Marvel.

She has won the Best Fan Writer and Best Semiprozine Hugo Awards, a winner of the D. Franklin Defying Doomsday Award, and was a finalist for the Best Game Writing Nebula Award. Her debut memoir, the Washington State Book Award-winning Being Seen: One Deafblind Woman’s Fight to End Ableism, was published by Simon & Schuster in 2021, and her Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla novel, Sword of the White Horse was released in 2022. Her episode for Radiolab in 2022, “The Helen Keller Exorcism,” is available here, and her episode of PBS' American Masters is here. Her activism has included actions as various as the Stop The Church protest at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City as a child, running the Join the Impact protest in Spokane, WA in 2007, Occupy Wall Street in New York City, the 2017 ACA Healthcare protests in Washington D.C. and assisting disabled protestors at Seattle’s Black Live Matters marches in 2020. She is available as an editor, writer, and public speaker upon request!

RESOURCES

- QueerTheology- The longest running LGBTQ+ Christian podcast,

- QueerGrace: An online encyclopedia for LGBTQIA + Christian life

- QG’s great book list.

- Dignity USA, Celebrating the Wholeness and Holiness of LGBTQIA+ Catholics

- Masgd: Muslim Alliance for Sexual and Gender Diversity

- Keshet which nurtures LGBTQ+ Jewish life

- Svara for Queer Talmud

- Shel Maala: A Digital-First, Queer Yeshiva

- The AIDS Memorial An online memorial for victims of the AIDS crisis on instagram.

- A Rainbow Thread: An Anthology of Queer Jewish Texts from the First Century to 1969 by Noam Sienna

RELATED POSTS

🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week. 🌱

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, that's how you can get tools for deeper transformation, a community for doing the work, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕