"Why Must I Die?!"

seeking better answers for Moses, and us

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

After the Exodus

After receiving Torah

After 40 years of trials in the wilderness, the midbar–

After telling the next generation about it all,

After the final covenant with the divine, the choosing of life,

On the edge of the Jordan River, on the brink of the Promised Land,

For Moses, at last, and too soon–

it was time.

God spoke to Moses on that same day, saying: Go up these heights of Mount Nevo in the land of Moav, and see the land of Canaan that I am giving to the Children of Israel for a holding.

You are to die on the mountain that you are going up, and are to be gathered to your kinspeople because you broke faith with me at the waters of Merivat Kadesh, because you did not treat me as holy amongst the Israelites. At a distance you shall see the land, but there you shall not enter the land that I am giving to the Israelites. (Deuteronomy 32:48-52, abridged slightly)

Setting aside the conquest narrative for now– we've addressed this in the past and will again in missives to come– there's a heartbreaking story at hand.

We've seen Moses evolve from infant refugee to privileged child of the palace; seen his tentative first steps of leadership through the Exodus and sea-crossing; watched him receive Torah and weather myriad ups and downs as he accompanied a traumatized people through four decades of uncertainty.

But there was that moment in the wake of his sister's death. He was grieving, possibly remorseful about how he'd left things between them, was overwhelmed by what may have felt like just more in an endless parade of complaints from the Israelites when he insulted his people and hit a rock twice when he was meant to have spoken. For this, (the character of) God decreed, Moses would not enter the Promised Land.

And now that moment has arrived, laden with pathos.

In the Torah text we do not see much response from Moses to God's directive; his last words are blessings to the tribes.

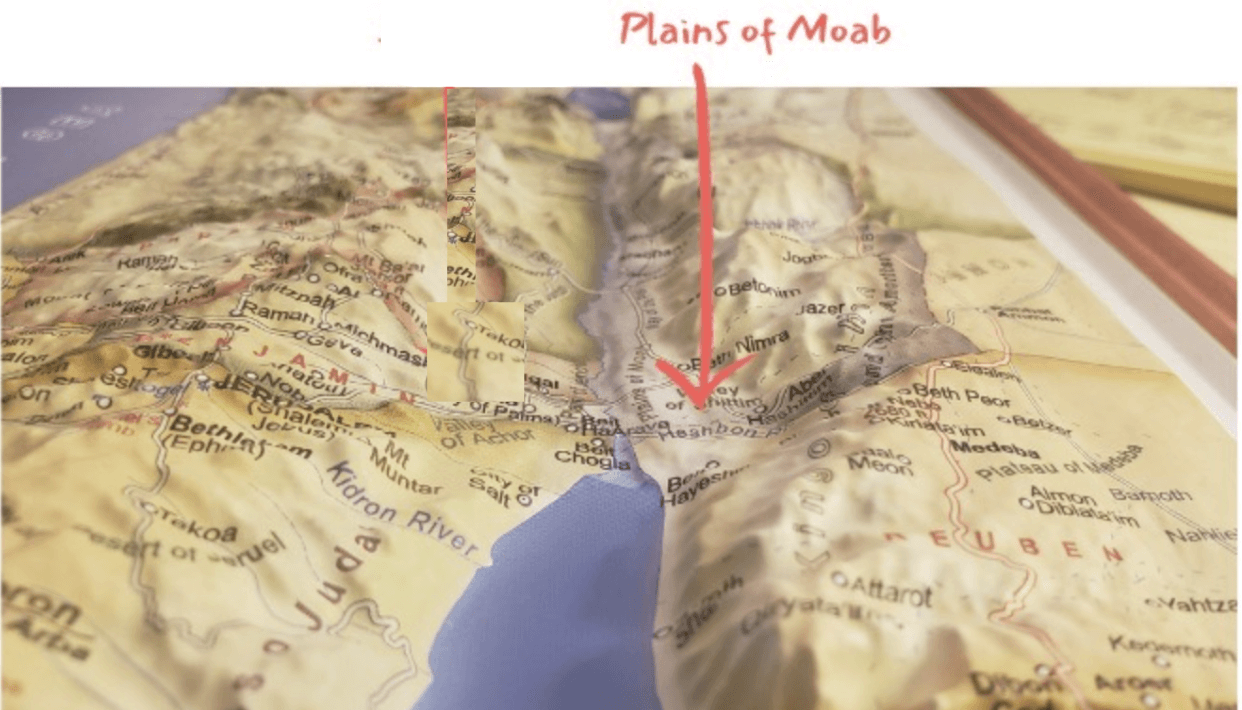

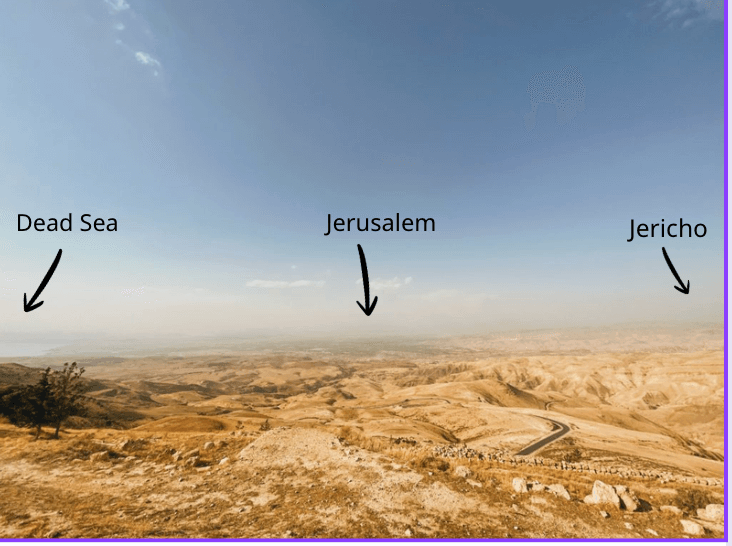

The Torah tells us that he ascends Mount Nevo, from whence he can see a tremendous view of the Promised Land:

But we don't hear Moses voice in all of this, not really. What was he thinking as he gazed upon this view? As he drew what he knew what would be some of his last breaths, looking at the place to which he would never arrive?

Was he sad? Resigned? Full of regret for his past lapse? Peacefully satisfied that he'd led a full – 120 year! – life and brought his people to the beginning of their next chapter?

Terrified?

Rava was at the bedside of Rabbi Nachman as he was dying. Rava said, "Promise me that you will show yourself to me in a dream after you die." He did so. Rava asked him, "Did you suffer much while you died?" Rabbi Nachman replied, "As little as when you remove a hair from milk. But if the Holy One were to say to me, 'Go to that world and be as you were before,' I would not wish to do so because the fear of death is so great." (Talmud Moed Katan 28a)

The Torah gives us scant information. If Moses struggles with God’s dictate, we aren't told. All we see is that he does as commanded.

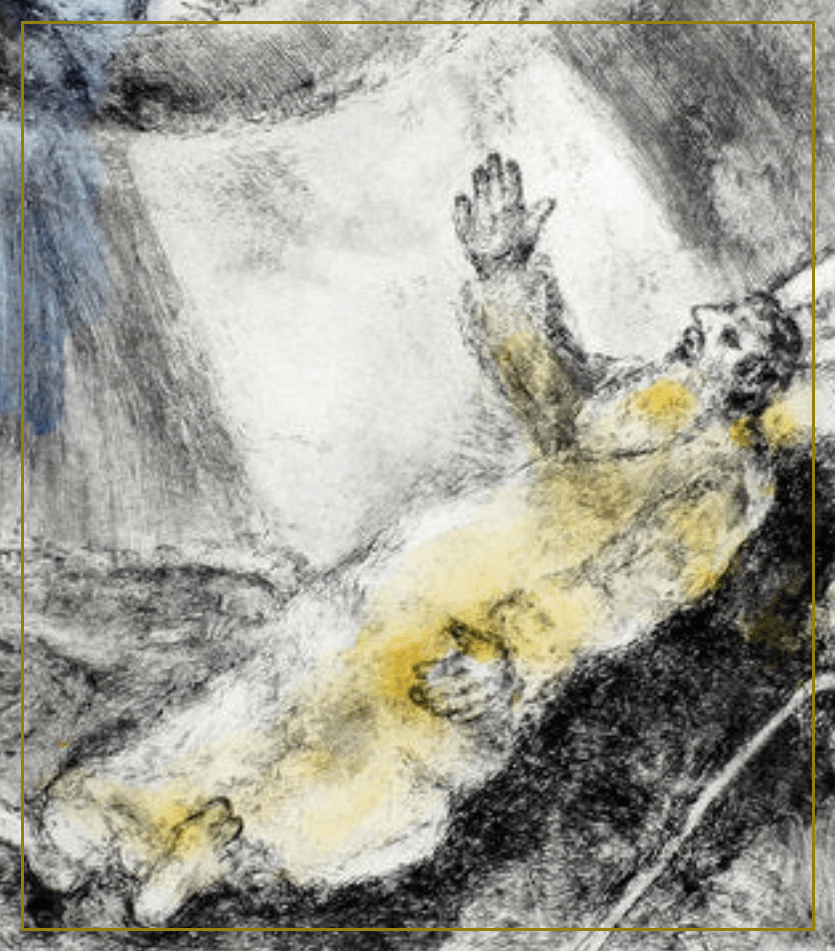

One midrash offers a very different view, showing Moses begging for his life:

Moses said to God, “Master of the Universe, why must I die? Is it not better that the people would say, “Moses is good,” by seeing this for themselves than that they would say, “Moses is good,” from just hearing about me? [he continues in this vein for a bit]...

God said to him, “Enough, Moses! This is the decree, and it's the same for all people.... The ministering angels said to the Holy One, “Ruler of the Universe, Why did the First Human die?” God said to them, “They did not take notice of [ie obey] me.” The angels said to God, “And behold, Moses did take notice of you!” God said to the angels, “The decree is the same for all people...." (Midrash Sifre Chapter 339)

The man who could be seen as an obedient servant in Deuteronomy here expresses outrage—or, at least, explicit fear—about his mortality, and lobbies for his own self-interest. Rather than mediating on behalf of the Israelites (as he often does in the Torah itself) he intercedes on his own behalf.

This Moses is so bold that God finally interrupts him with, “Enough, Moses!”

What's God's rejoinder to this high-stakes appeal? Not, interestingly, to mention the rock-hitting incident– that is, to tell him that this is punishment for his actions.

That would be the logic of the Ancient Near East, in Deuteronomy and beyond: If you do good, if you choose life, you get blessings. You don't get curses, death and badness unless you deserve it. We also see this all over Prophetic texts—a common explanation for the destruction of the First Temple and subsequent Babylonian exile is that, well, the people of Israel sinned.

Moses here seems to implicitly suggest, even, that he doesn't deserve death after all his great works, if that's the rubric. He's good, he did all these great things for the Israelites, etc. Midrash God doesn't dispute any of that. But none of it matters.

The early Rabbis* witnessed their own civilization destroyed by the Roman Empire: First, the traumatic razing of the Second Temple, and then the extreme, punitive response to the Jews' failed Bar Kochba Revolt.

Among many horrors, the most righteous, holy sages of their own generation were tortured and slaughtered by the Romans. One imagines that the early Rabbinic midrashist couldn't consider a question about why people die– about why, in a sense, bad things happen to good people–with trite adages about sin and punishment.

Like us, they saw good people suffer unjustly.

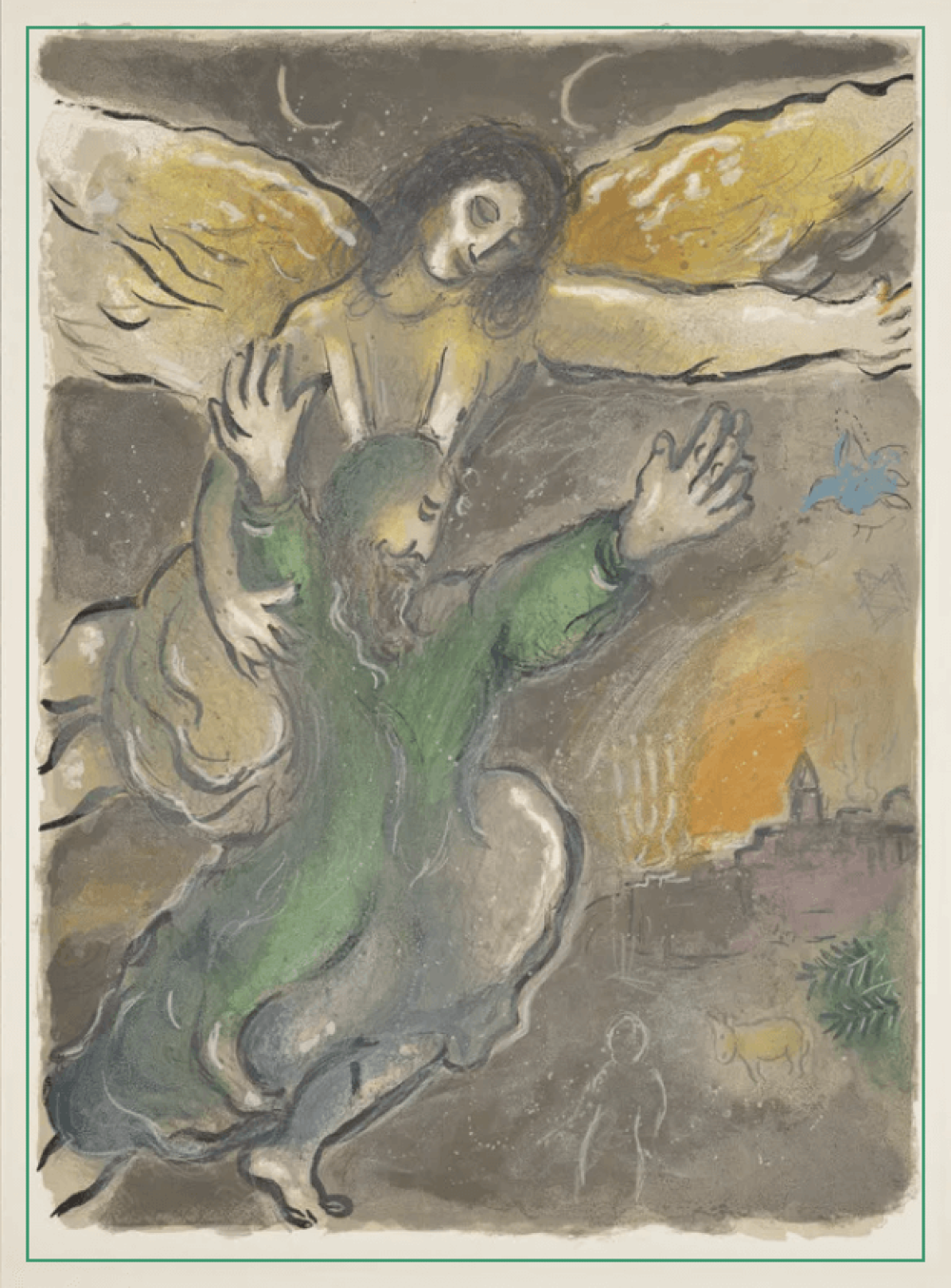

*This is, indeed, a very early midrash, just about the earliest layer of midrash that we have, written in the same Hebrew as the Mishnah and beleived to be contemporaneous with it, ca. 200 CE or earlier.So they give us angels who challenge God on Moses' behalf– unlike the First Human, Moses “did take notice of” God’s words. He was good!

But then when God echoes God's earlier statement, it packs a heavier punch:

“The decree, she is the same for all people.”

However mortality began (thanks, First Human) it's a thing now. For everyone.

Doesn't matter how much your deeds merit.

It’s not necessarily logical, and it’s not necessarily fair, but, the Rabbis tell us, it's the truth. And the truth matters.

Interestingly, God never offers a direct answer to the question: Why must people die?

They just do.

This is just what happens.

And whether or not we like it, whether or not it's "fair," we have to accept it, because this is how real life actually is.

Which doesn't mean– as the Torah and the Rabbis teach us, again and again and again– that we shouldn't do everything in our power to try to try to use our divinely-given free will to create a more whole, more holy world for all the human beings in it to the full extent that we can, every single day, with all of our power, in all the ways that we can, to try to protect and preserve life, and then to love.

That's still and always our most important job while we draw breath.

But this means that, ultimately, none of us are exempt from the end of the story, whenever and however it happens– please God may it be a long time for all of us, and may we all thrive.

No amount of privilege, performative actions, capitulation to power or amassing of wealth will exempt us from this basic truth.

So we may as well show up and be the people we were meant to be, and live the life full of honesty, care, compassion and honor that is always available.

Day by day. Choice by choice. Act of love by act of love.

However the story ultimately ends, we have the power to write so much of who we are.

Moses went up from the Plains of Moav to Mount Nevo, and God let him see all the land.... There died there Moses, the servant of God, in the land of Moav. ...

But there arose no further prophet in Israel like Moses,

whom God knew face to face,

in all the signs and portents

that God sent him to do in the land of Egypt,

to Pharaoh and to all his servants, and to all his land;

and in all the strong hand

and in all the great, awe-inspiring [acts]

that Moshe did before the eyes of all Israel.

(Deuteronomy 34:1-12, abridged)

Share this post

It's easy to attempt to do right by our friends, family, loved ones, acquaintances, and the people we simply encounter day-to-day– and often hard to get it right. Join us for a lively, interactive conversation around the ethics of interpersonal interactions and you might find that it proves transformative in the next sticky, or almost-sticky, situation.

February 8, 2-3:30ET, 11-12:30PT

A reminder about the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable. ❤️ 🌱

When you sign up for the House of Study, you get deep dives every Thursday, Ask the Rabbi Q & As, monthly Zoom Salons IRL, access to over 4 years of archives, a study partner if you want one, and so much more-- and you DON'T have to get more email if you don't want! Don't you deserve all this nourishment and support??

As always, if you want in on the House of Study, but paying isn't for you right now, email support @ lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

Support independent work committed to telling inconvenient truths:

RELATED