The Rock that Broke

...And the heart that broke with it.

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

This week we're looking at a heartbreaking story that has a lot going on in it– and that might be able to reveal some things about how some of us engage with thorny emotions like pain, grief, and anger, as well. .

Sometimes it's helpful to do a lot of framing upfront, but today I want to just get into the story, so that we can talk about the story.

We're in Numbers 20:

The Israelites arrived in a body at the wilderness of Zin on the first new moon, and the people stayed at Kadesh. Miriam died there and was buried there. The community was without water, and they joined against Moses and Aaron. The people quarreled with Moses, saying, “If only we had perished when our brothers perished by God's will! Why have you brought God's congregation into this wilderness for us and our livestock to die there? Why did you make us leave Egypt to bring us to this wretched place, a place with no grain or figs or vines or pomegranates? There is not even water to drink!” Moses and Aaron came away from the congregation to the entrance of the Tent of Meeting, and fell on their faces. The Presence of God appeared to them, and God spoke to Moses, saying,

“You and your brother Aaron take the rod and assemble the community, and before their very eyes order the rock to yield its water. Thus you shall produce water for them from the rock and provide drink for the congregation and their livestock.”

Moses took the rod from before God, as he had been commanded.

Moses and Aaron assembled the congregation in front of the rock; and he said to them, “Listen, you rebels, shall we get water for you out of this rock?”

And Moses raised his hand and struck the rock twice with his rod. Out came copious water, and the community and their livestock drank.

But God said to Moses and Aaron,

“Because you did not trust Me enough to affirm My sanctity in the sight of the Israelite people, therefore you shall not lead this congregation into the land that I have given them.” (Numbers 20:1-12)

Let's start by making sure everyone's on the same page:

Miriam is water. She's always by bodies of water, whether the Nile or the Sea of Reeds (also here). Immediately following the first mention of her name in Exodus 15, we hear about the challenge posed by the waters of Marah, the undrinkable bitter waters. When she dies, the people are suddenly without water. According to Midrash (Numbers Rabbah 1:2), Miriam had a well that traveled with her throughout the desert with the Israelites, and the cries for water here are because her well dried up with her passing. (1)

And in the wake of Miriam’s death, we must consider her relationship with not only the Israelites, but one of her brothers in particular.

We see Miriam speaking against Moses in Numbers 12, and we see her punished— cast out of the camp— for doing so.

But we do not ever, on the page, see the siblings reconciling, even though a panicked Moses does beg God for her to be healed when she is struck with tzaraat.

We talk, sometimes, about the white spaces in the text— about what isn’t said.

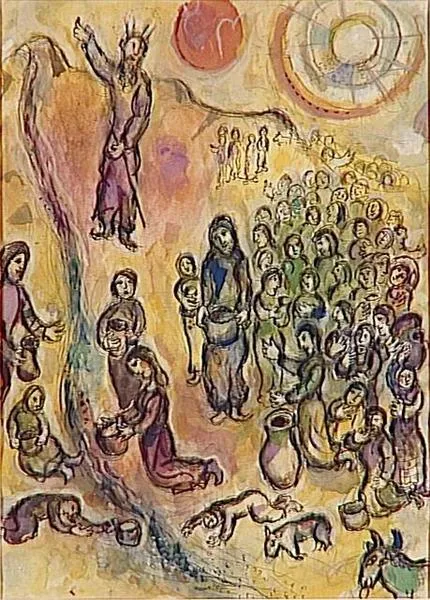

(2)

Those white spaces are the openings for midrash, yes, invitations— but they're also questions.

Did Moses and Miriam ever speak meaningfully again after their rift?

Did they reconcile but it was never quite the same, with hurt and angry feelings still lingering under the surface?

Did they find the tender beginnings of reconnection but needed more time for things to heal more fully?

Were things great, actually— better than before, finally months and years of things unsaid brought to light, and Moses had just finally begun to have a sister in a whole new way?

We don’t know.

But we know that here, Miriam dies.

And it becomes Moses’ undoing.

And/though for Moses, this moment is complex, multilayered.

If the Red Sea was the birth of a new nation through the waters, the irascible toddler years of this people have been too much, so much for Moses.

One can imagine how exhausted he must be—even before his sister's passing, he's had to deal with their longing for cucumbers and melons, the challenge from Miriam and Aaron, Miriam’s illness, the panicking after the spies’ return, Korach’s rebellion, and so much more in this desert space.

And he may have felt especially bereft at this point. Korach and the Golden Calf were bad enough— and rebellion and idolatry have concrete solutions, at least.

But the refrain he hears, again and again— these endless, unquenchable desires, this blaming him despite all of his efforts, this nostalgia for enslavement….

This is something that will never be able to be filled or fixed.

As the late writer Caroline Knapp put it,

Food, sex, shopping: Name your poison. Appetites… have an uncanny shape-shifting quality, and a remarkable talent for glomming onto externals. One battle segues into the next, one promise proves false and another one emerges on the horizon, glimmers, and beckons like a star…. All of these are about emptiness, about misdirected attempts to fill internal voids, and all of them tend to spring from the same dark pool of feeling....

The people are demanding something external to fill an internal void.

It's an unwinnable proposition.

Moses is tapped out in his capacity as leader—he has given and given and given and he has not been refilling his own well, as they say.

The Israelites' complaints and reactions– their internal void– has remained more or less the same for chapters and chapters, so many steps in this journey.

Moses hasn't been able to help them learn how to handle their problems in a different way. Perhaps he doesn't know how to.

And now he is grieving his sister; he is possibly bereft, maybe full of regret, holding all that has been left unsaid. Or maybe he's furious that a new relationship has been stolen from him all too quickly.

We don’t know.

But Miriam is dead and the Children of Israel are probably also grieving their beloved leader and prophet, possibly panicking because of her well has dried up— and they are complaining again.

Moses is grieving and burnt out, but, unfortunately, he is the one in charge.

Well– he was one of the people in charge. This was a moment when Moses could have stepped back, here, but he didn't.

God told Moses and Aaron to take the rod, assemble the community and order the rock to produce water. If ever there was a moment for a crispy prophet to delegate, amirite? But Moses just grabs the thing, insults his community (thought by some commentators to be the real sin, here) and whacks at the stone, instead.

The Israelites weren't the only ones who needed time in the "calm-down corner."

Here is a story that I have heard about Rabbi Yisrael Friedman of Ruzhin, also known as the Ruzhiner Rebbe, (1796-1850, in what's now Ukraine):

Once, he came upon one of his sons getting angry at a particular Hasid/disciple; and when the son finally noticed his father, Rabbi Yisrael didn't say anything, leading the son to somehow get even more upset. The Ruzhiner finally silenced him and said:

"Regarding Moshe Rebbeinu [Moses our Teacher]: Hitting the rock twice was considered a sin, for: One time it’s possible for a person to go out of their boundaries and to get upset. But if a person returns to this (behavior again), behold–this is a sign that they are an angry person, and anger is a disgraceful trait. And the Sages said [in the Talmud]:

'The Holy One gets angry every day, and how much is God's wrath? A moment, as it’s said (in Psalms 7:12), "God's anger is a moment."'(Talmud Brachot 7a):

From here, it’s possible to teach that a person should not be angry for more than a moment, like the anger of the Holy One. And Moses, because he hit (the rock) twice, it was revealed that he stood on his anger more than the appropriate amount, and so he was punished."

Everyone is in their anger sometimes.

Everyone gets upset sometimes! Everyone neglects to step back when they should in the thick of the moment sometimes– or doesn't have anyone to whom they can pass things off, or forgets to go to the other room for a couple of deep breaths before responding in the middle of a tense situation.

Rabbi Yisrael is saying here that a momentary breaking of one’s calm exterior is understandable and forgivable—even God has a slight lapse each day.

So the question here becomes about our relationship to anger.

And, candidly, I'm less interested in, "How do we make sure we don't cross some magical invisible line forevermore?" than, "How do we keep ourselves from causing harm with our anger?" and, even, on a deeper level:

How does anger serve– and not serve– us, and what might happen if we were honest about all those ways?

Certainly, anger serves a number of valuable roles as a response to evil: It can help us to see where our boundaries are; it gives us a forceful response to a injustice; it moves us to action.

A primal scream can be a release that helps us exorcise the hard feelings so that we can move forward in catharsis. If evil is a disease, anger can sometimes function as the white blood cells that rush to our body’s defense—a healthy evolutionary response to a legitimate threat. After all, the Mishnah teaches,

As long as evil people exist in the world, fierce anger exists in world; once the evil ones are removed from the world, fierce anger will be removed from the world. (Mishnah Sanhedrin 10:6)

(I keep telling you, the Rabbis of the Mishnah lived under the Romans and they didn't have time to play around.)

But so often we see anger wielded as a sword when it’s really serving as a shield.

Wherein lashing out happens when, upon closer examination, anger is being used as sort of a scab to cover over and protect deep woundedness and pain.

Anger might be comfortable in its familiarity; even the adrenaline and the cortisol, which can build up in your body and cause chronic issues, is a known sensation, one to which we sometimes choose to return again and again and again.

And anger is a feeling about having power, even if, underlying the whole situation, one does not have power. It is often a way to try to exercise control when we are feeling least in control.

Look at Moses:

His sister dies. His community demands water. He is told what to do. He is not in a position where he has much, if any, real power or agency here, even if he’s technically the guy in charge.

We do not see him mourn. We do not see him acknowledge his frustrations with the people. We certainly do not see him sensibly hand off the gig to his brother or whoever else.

Rather, God’s Chosen Prophet goes just a smidge ballistic.

He takes his feelings out on the rock instead of — what, the journal, the therapy session, the meditation cushion, the prayer experience, the scream out in the woods, the running shoes, the list goes on. Better that he didn’t take it out on a person, yes, granted.

But instead of making conscious, intentional space for the rage, let alone his actual feelings of sadness, sorrow, grief, pain, regret, exhaustion, uncertainty in his own leadership or whatever else, he allowed the anger to overshadow those feelings- to cover them up.

And to do damage in the meantime.

Moses didn't make space for his more frightening, more vulnerable feelings, so his anger came in to protect him from them, ultimately further delaying the time before he would face his sister’s devastating loss. He lashed out at his community rather than sit with this engulfing loss or any of his questions about his competency as the leader. (3)

This time, it was self-destructive. Other times, it might harm others, too– like Rabbi Yisrael's son berating the disciple. And every time Moses sidesteps engaging honestly with how he's really doing, he misses the chance to deal honestly with himself, the parts of own heart that need care and attention.

So how can we deal with the anger that we use as a shield against our own pain?

Even if this makes sense in theory, we can’t, like, just automagically short-circuit our emotional reactions….

Can we?

You know what I’ve discovered in my years as a rabbi?

I have found that when start wondering what our anger is covering over, we can start to peek around the edges of the pain. We can start to glimpse it.

At first, often, it might seem like we can’t bear it. Like we might die if we allow ourselves to even see what’s there, what’s been there all this time.

But once we can regard the anger as a scab, just notice the existence of the pain, it’s harder to stop looking.

And eventually once we see the pain, it gets harder and harder to ignore, and, like a scab, the anger eventually falls off as curiosity about the pain becomes stronger and stronger. And then— oof.

The pain is given air and light.

(There might be tears.)

(None of this would be a bad idea to do with the help of a supportive and skilled therapist).

But once the pain is aired out, it can then (whispers) begin to heal.

As meditation teacher Sylvia Boorstein put it,

If I say to myself, “This is painful, but it’s O.K.,” and I stay there, then it’s just what it is and then it changes. But when I run away from it or I push it away or pretend that it’s something else, that is the suffering. All those maneuvers that we do to avoid saying, “This is true. Th is is what’s happening”— the maneuvers themselves are the suffering.

The less concerned we become that the pain will kill us, the less we're less likely to push it away.

Even God* gets angry. That’s not the problem. God* doesn’t STAY angry is the thing. God doesn’t HOLD angry, God doesn’t CLING TO angry, God doesn’t ACT from angry.

*the literary, anthropomorphized character of, that is

The more we can remember that we are not our feelings, but that our emotions are just one type of truth that we experience, the easier it is to not feel defined by them, or to assign more significance than necessary. When we’re able to understand the power that we have as hosts to these feelings that have come for a visit, we can be more magnanimous with the irritation and sadness when it comes, but feel less and less driven by it, more in control of our heads and our hearts. (4)

Moses in grief, Moses in pain is so many of us in so many different ways, especially now.

Especially in light of a paradigm-shifting global pandemic that our wider culture is still pretending was no big deal. In light of the horrors that have, that continue to take place in the Holy Land. In light of the global rise of fascism, attacks on civil and human rights, climate destruction, and all of the personal traumas and everyday struggles that everyone is holding.

Of course, rather than naming our vulnerabilities, our fears, our uncertainties, our betrayals, our suffering, we so often push them down, often unconsciously, and allow our focus to remain on that burning anger, right at the surface.

If Moses had allowed himself to mourn — or if he had been able to even pause long enough to see how impacted he really was by Miriam’s death, or how exhausted he was generally — perhaps he would have made different choices.

We still can.

🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱🌱

Like this? Get more of it in your inbox every week. 🌱

For free every Monday—sign up at the ‘Subscribe now’ button just below.

And if you become a paid subscriber, that's how you can get tools for deeper transformation, a community for doing the work, and support the labor that makes these Monday essays happen.

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕

Lastly, a reminder that tomorrow (Tuesday) night, I have the humbling honor of receiving an award by the incredible, wonderful human rights org T'ruah, so if you'd like to join us virtually (I think we're sold out IRL), please do!

[1] Miriam and water

[2] White spaces in the text

[3] Angry Moses

[4] Rumi

Yam, ים, sea, right there in her name. (מִרְיָם) Her name is often translated as "bitter sea," from the root מר, but Prof. Rabbi Wendy Zierler suggests that the root might be מור– that is, “to change,” “alter,” or “exchange.”– thus leading to a meaning more like,“Changing Sea” or “Transforming Sea.” All this water business is why some people have a cup of water for Miriam at Passover to go with the cup of wine for Elijah. I’ve heard speculation over the years (can't for the life of me remember where, though) that she might be some sort of remnant of a sea goddess-type archetype, but the fact that I can't find any decent scholarly backup even for that kind of thing tells you— well, something about that. If you are someone who can find decent scholarly backup, please do alert me! ↩︎

Or, more beautifully put in Midrash Tanchuma, Genesis 1:1:

"How was the Torah written? It was written with letters of black fire on a surface of white fire." ↩︎Yes, anger is one of the famous Kübler-Ross stages of mourning. But again: Feeling anger is different from acting out in anger. They are not the same. We always have control over how we treat ourselves, each other, and the world around us. ↩︎

Yes, some of you may be hearing allusions to a famous "Rumi poem," but "The Guest House" is, I'm sorry to be the one to tell you, not actually "a Rumi poem." It's an excerpt of the Masnavi, a 50,000 line “Quran in Persian” that Rumi wrote towards the end of his life. The famous Coleman Barks translation is pretty snappy and quotable, but many Farsi speakers have what to say about his, uh, loose, interpretive translations. Here's another one I've come across that's hopefully a bit closer to accurate: “Every day, too, at every moment a thought comes, like an honoured guest, into your bosom. O soul, regard thought as a person, since a person derives his worth from both thought and spirit. If the thought of sorrow is waylaying joy, it could also be considered as making preparations for joy. It violently sweeps your house clear of everything else, in order that new joy from the source of good may enter in. It scatters the yellow leaves from the bough of the heart, in order that incessant green leaves may grow. It uproots the old joy, in order that new delight may march in from the Beyond.” Notably, Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, a Polish rebbe who eventually taught from the Warsaw Ghetto, uses this same metaphor in his own work, writing that "A person . . . is a mere inn for the thoughts of the world that are passing and returning, going and coming, and the essence of the person is not to be found. . . . Just as time and the world change, so do they [i.e., their thoughts]. . . . First the [thoughts] were bad guests and now they are good, [revolving] according to the world and the day. . . . " ↩︎