Jewish women's folk ritual

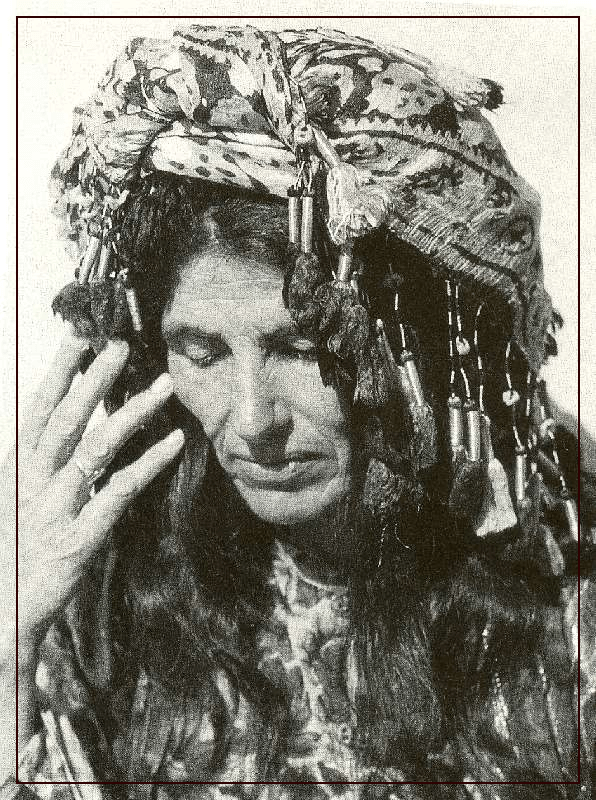

wise women, healers, banishers of the evil eye (puh puh puh 🪬🧿 ) and more, across the globe

This is Life as a Sacred Text 🌱, an everybody-celebrating, justice-centered voyage into ancient stories that can illuminate our own lives. It‘s run on a nonprofit, so it’s 100% NAZI FREE. More about the project here, and to subscribe, go here:

Today's post talks about Jewish communal rituals that have traditionally been connected to communities of women. We'll be talking a lot about gender, and it's a very cisgender-default conversation. That doesn't mean that there were never any trans, intersex, gnc or nonbinary people in any of these times and places– there were, of course. More on all that here.)Today's post shares a lot of amazing practices from around the world.

It is not a grimoire. Please do not start taking up a ritual practice because you read about it here. Please definitely do not appropriate. Practices have contexts and histories and traditions, and while there are folks working to revive old and lost traditions (as you'll see, including links to some of their websites and guides), that work has more process than one generalist's newsletter. Those folks are great people to connect with if you want to plug into this kind of work.

Imagine a continuum of spiritual behavior, with the normative men's prayers at one end. The official Jewish record of spiritual striving (that is, the rabbinic literary corpus) records only that end of the spectrum...It is as if women walked through history carrying spiritual flashlights from which there emanated only infrared wavelengths, in a world where an automatic light detector recorded only ultraviolet. Whenever the flashlight threatened to reach the ultraviolet spectrum, it was deemed as malfunctioning and taken away by the light keepers in charge of ultraviolet transmitters. Meanwhile, a detached observer of social behavior in general would record (from time to time) traces of infrared radiation, but having defined light according to the other end of the spectrum, it would never occur to anyone to call it light, record it in detail or treat it seriously.

(Lawrence Hoffman, "Women's Prayers and Women Praying.")

Not long ago, we talked about how the Rabbis described all sorts of of Jewish women's practices as witchcraft– including ways of healing; cooking; tending; spiritual traditions and more– for any number of reasons. (Even though the Rabbis themselves did things that could clearly be defined as magic.)

Today we're going to look at Jewish women's practices that skirt that place around tradition, spirituality, healing, the mystic, and who knows what else. Note! I honor with the greatest seriousness these women's own relationships with Judaism and God, and do not presume to understand them from the inside. I simply thought that moving from the Rabbinic gaze on women's lives to what little I can report on those lives lives flowed nicely.

As I hope began to in the other post, let us continue to topple the false construct between "religion" and "magic." The male-authored Sefer Yetzira (The Book of Creation) is certainly magic. Harba deMoshe (The Sword of Moses)? Mmm.

As Hebrew Bible professor Nancy R. Bowen puts it,

In general a society will distinguish between that which is a socially approved or acceptable form of action and knowledge (religion) and that which is a socially disreputable or unacceptable form of activity and knowledge (magic).

Yeah. So this is Jewish women, doing things. That are Jewish.

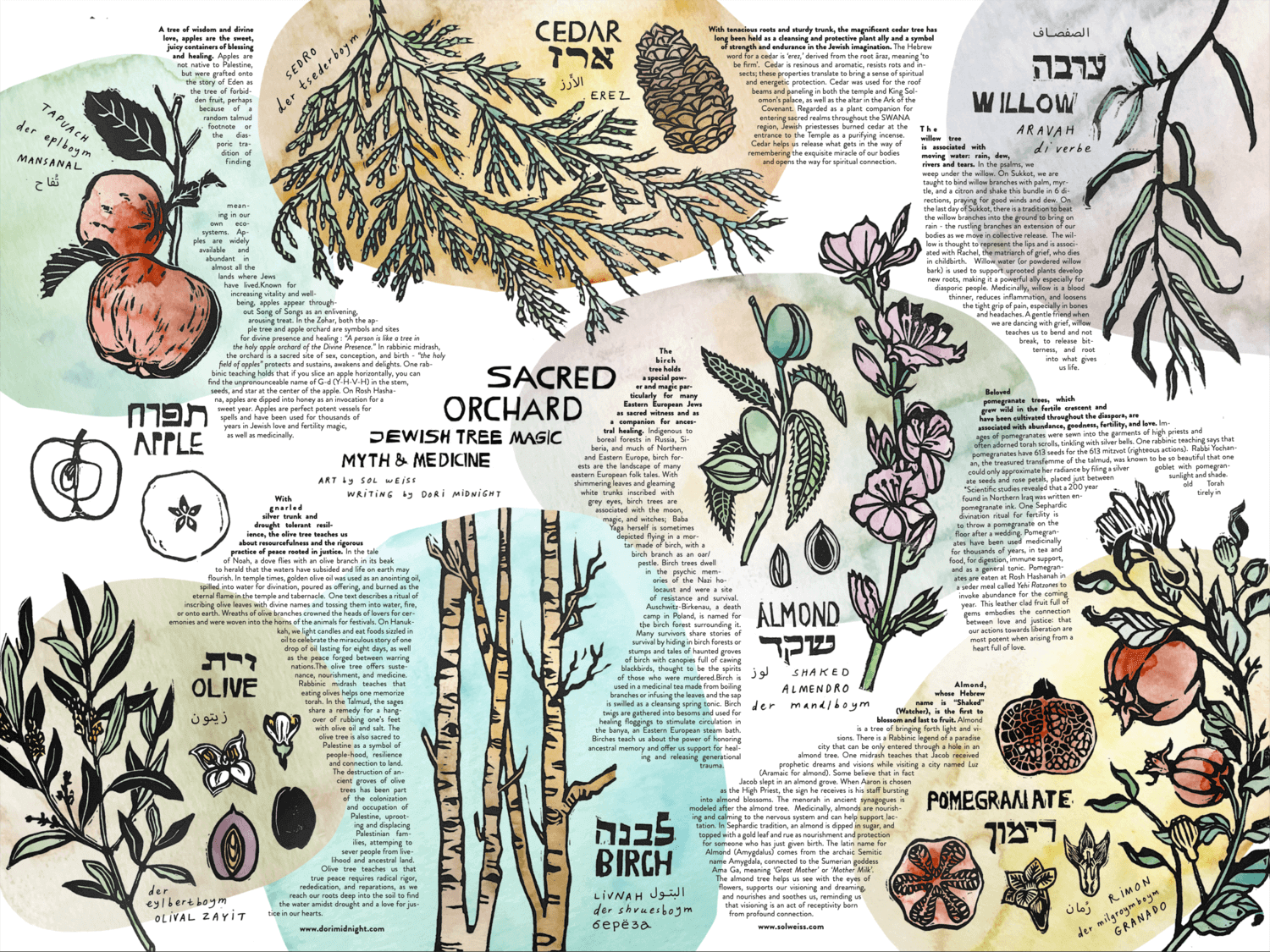

Jewish women in Kurdistan– a very ancient Jewish community– took on a vast number of important ritual roles, from that of the formal mourner; expert storyteller of an independent women's tradition; embroiderer of amulets; and officiant at ceremonies designed to protect families and communities from evil spirits.

Susan Starr Sered reports that after a new home was built, for example, women would

"pour a bit of water and wave a cloth over each hand and say [in Kurdish,] 'Get out, go from here devils. Enter good spirits. You should have sons and daughters, grooms and brides.'"

Teachings from the women in the community when someone became pregnant for the first time

"included information about properly disposing of fingernail pairings so as to avoid miscarriage,"

and other charms related to fertility and easy labor.

Asnat Barazani– the late 16th-early 17th c. Torah scholar and mystic known sometimes as the first woman rabbi– was from this community.

Unfortunately, unsurprisingly, even by the time of Sered's work in the early 1990s, many rituals had disappeared as a result of modernity, colonialism, and the priority placed on male-approved ritual life during a time of great social upheaval– most Kurdish Jews were forced out of Iraqi Kurdistan in the 1940s and 50s, along with the Iraqi Jewish community.

Many Ashkenazi* wise women– midwives, healers, cemetery ritualists, professional mourners, etc– were also treated with great respect. When a midwife died, the room would be illuminated with one candle for every soul she brought into the world.

As elsewhere, the line between "healer" and "folk magic" were nonexistent. One account of a particularly dangerous labor features a Jewish Russian midwife demanding that all the doors of all the closets and all the drawers of every dresser to be pulled out and opened. ‘Rolling eggs.’ involved circling a raw egg over the ill person's body plus an incantation or blessing– this could be used to heal or diagnose, depending.

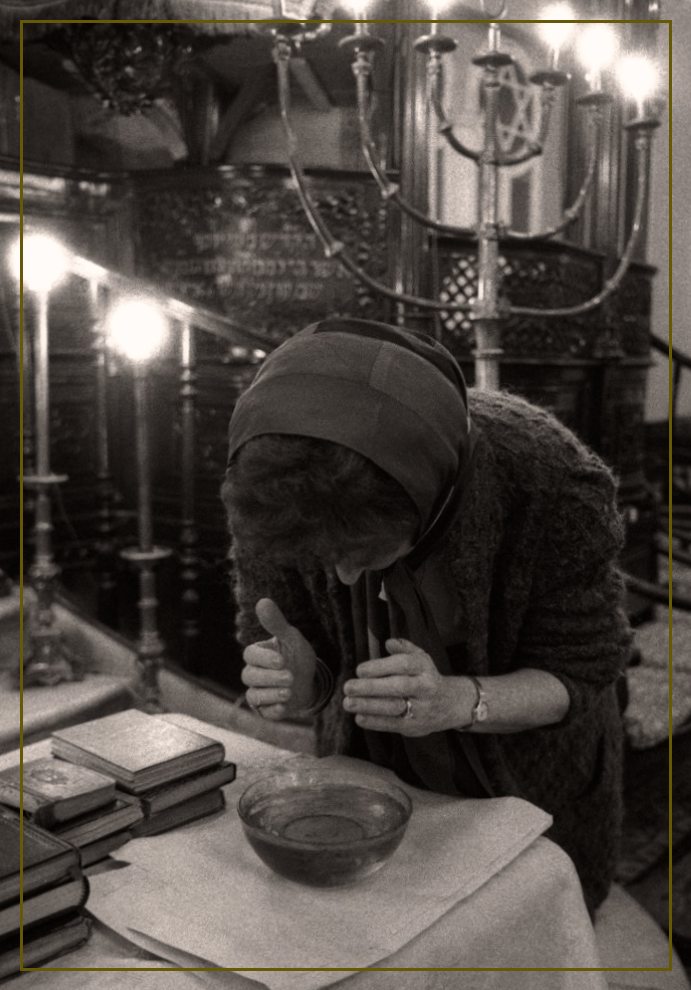

And many midwife-healers also practiced things like blei gissen, also known as ‘pouring lead’, (molybdomancy), a divination practice that included melting lead (or wax) and then pouring it into a bowl of water over the afflicted person's head. The head was covered with a sheet, and incantations were prayed. This continues in some communities today.

And, as Annabel Gottfried Cohen, a Modern Jewish History PhD student at JTS – who has done some very important work in this area– explains:

In many Eastern European Jewish communities in the week between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, women would gather to make soul candles or neshome likht. The tekhines [or Yiddish prayers] recited when making these candles called on the dead to help the living on the Day of Atonement by advocating with God for their loved ones.. ...In many places, the wick for the soul candle was made from a thread that had been used to encircle or “measure” the local cemetery. The wick for the “living candle” was made either from a second cemetery measurement, or by measuring the height of each living member of the family.

More on soul candles here, where she writes,

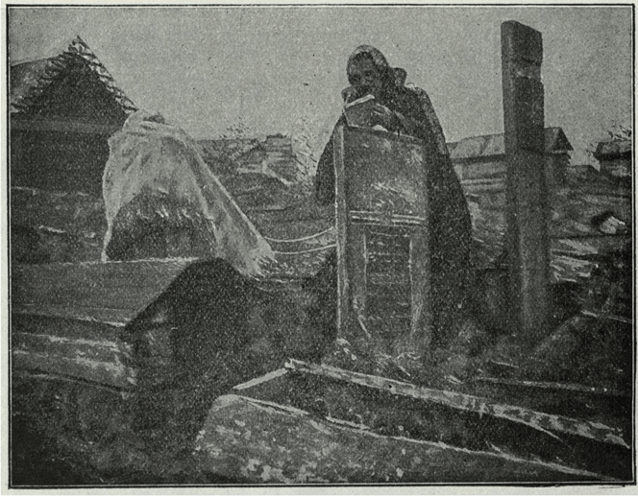

In cases of severe illness or very difficult childbirth, Jewish women in Eastern Europe turned to a ritual known in Yiddish as feldmestn or keyver-mestn – cemetery or grave measuring. Often a last resort when other remedies had failed, the graves of close relatives of the suffering person were measured with thread, accompanied by Yiddish tkhines (supplications) calling on the dead to use their position in heaven to plead with God on behalf of their relative. The thread was then used as the wick for special neshome likht or ‘soul candles’ that were donated to the synagogue or the beys-midresh (the house of study). It was hoped that this mitsve [commandment] of donating candles to light up the study of Torah would invoke God’s mercy.*Ashkenaz is the Hebrew word for Germany, and Ashkenazi generally refers to Jews of Germany, Eastern Europe, and often France and other regions as well.

get more like this on the regular

Two grainy black and white photographs. of women wrapped in scarves. L: Three feldmesterins in South Russia measure the cemetery during the month of Elul. R: A feldmesterin measures a grave while her client reads from a prayer book, possibly the Maane-loshn or Ma’abar Ya’avok, seventeenth century books of prayers in Yiddish and Hebrew which were frequently used by female cemetery ritualists. Thanks to Annabel Gottfried Cohen for these photographs and captions. Learn much more at her site.

L: Annabel Gottfried Cohen, Kohenet Shamirah Chandler and others revive the practice of the neshome likht/soul candle. Measuring the Workers’ Circle section of Mount Carmel Cemetery, Queens, in 2022. R: Various ads in Yiddish Brooklyn newspapers blei gissen (pouring lead). Thanks to Frieda Vizel for the ads and thoughtful putting of pieces together here.

While I've had difficulty accessing good work on the ritual lives of Beta Israel (Ethiopian Jewish) women, Rabbi Dr. Sharon Shalom, a leader in the Beta Israel community reports that traditionally

From her third month of pregnancy, the woman receives support from a professional called a bale tet (“wise woman”) She advises the pregnant woman on what she should and should not eat, and other advice to ease the pregnancy. She also helps with housework.

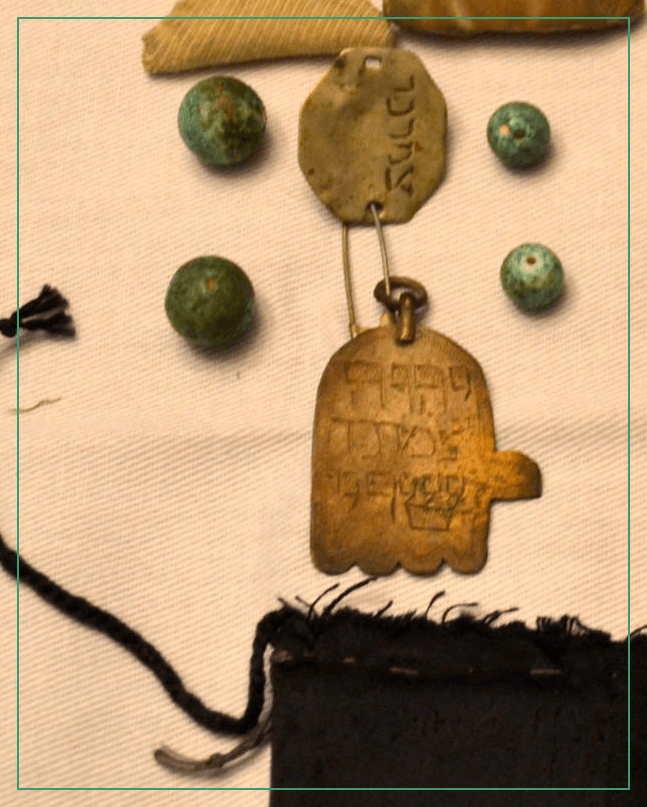

During pregnancy, the woman wore a necklace made of conch shell around her neck, which was a charm against miscarriage, and she also carried an amulet to protect her from harm. The birth takes place beside the entrance to the home. After the baby is born, they declare the sex. The midwife is responsible for the joyous announcement, and it is declared by signaling through [the number of] ululation[s]... Why did they use ululation instead of words? This was to express joy, and so as not to tempt Satan. (Shulhan haOrit; The Laws of Ethiopian Jewry, Bride, Groom, and Family, 12:3)

There is an extraordinary book, Ritual Medical Lore of Sephardic Women: Sweetening the Spirits, Healing the Sick, by Isaac Jack Lévy and Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt that focuses on the Sephardim* of the Ottoman Empire (specifically the Balkans, Dodecanese Islands, and Turkey, and their descendants) over forty years, capturing elders' memories of their elders, full of stories, details, specifics, and variations– truly, the book is incredible if you're interested in this.

Like Ashkenazi women– and presumably like the Beta Israel bale tet and the Mizrahi Kurdish women mentioned above– those engaged in the healing arts were profoundly well-regarded. Sometimes they were called a doktora sin chanta, a doctor without a bag, also described as mujeres santas (saintly women) mujers bendichas (blessed women), sadikas (holy women) and so forth.

I could spend a year just covering its contents, but for now, I'll lift up one ritual: The prekante.

It's a ritual prayer for curing any kind of serious illness, releasing the evil eye, evil talk, any kind of harm. The word is related to Portuguese and Latin words for both sorcery and foretelling, and it's speculated that the practice predates the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492– and, indeed, there seems to be some documentation from the Inquisition to back this up.

The prekantadora, who performed the prekanes, was, as other wise women, deeply respected in her community. The prekante was ideally performed at the beginning of the Hebrew month, when the moon was growing– not shrinking– and ideally on Monday or Thursday, weekday Torah reading days. It was done with whatever was available–

"by taking a handful of sugar, salt, or cloves, and passing it in circles over the head, and sometimes in front of the face and around the shoulders and chest, while repeating a verbal formula. For the evil eye** or espanto** one could burn cloves in a [special] procedure..."*Sepharad is Spain in Hebrew, and the Sepharadim are the Jews expelled by Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492; they retained many aspects of their unique culture, even as they were scattered to various parts of the Mediterranian, the Ottoman Empire, and elsewhere.

**The mal ojo, evil eye, was said to feed on envy or greed, whereas (if I understand correctly) espanto translates to "fright" or "terror" and is related to a spiritual imbalance that comes from receiving a shock or surprise.

If possible, one would go to the sea, for, as one elder said,

"The sea is deep and can endure anything."

The prekantadora would perform the ritual three times, and while reciting the prekane, would pass her hand over the ill person's body, she would symbolically cut the disease from them with a black-handled knife. At the end of the ritual, she'd dissolve the salt she'd been holding into water and wash the afflicted person's face, legs and arms. Sometimes words like, "as the salt dissolves in water, may all harm dissolve," were spoken. Or, if burning cloves, were used– "may they burn away evil," or, if they exploded, "as these cloves explode, may the eyes of whoever has seen her explode with them."*

Here are the opening lines, in Ladino and English, of a prekane against the ojo malo (chas v'shalom puh puh puh keinahora🪬):

Pur un kaminiku pasi, Kun un viezijiku 'skontri. Ali vedri vistia, Tres yavizikas tenia en su mano, Una d'avrir, una di sirar, una di kitar todu il mal. Ben pura Yusef, ben pura adalai.

As I walked along a narrow street, I met an old man, in resplendent green, he was dressed,*This is the English translation of the Ladino.

Three keys he had in his hand,

One to open, one to close, and one to remove all harm. May the sacrifice of Joseph, God, be accepted instead of mine.

Needless to say, there are far more stories and practices than I could possibly share here; this is why I've assembled a ✨BOOK LIST✨ so that you can extend your own education in various directions; some of the books are more about the history of the practices described today, some weave a future from these threads; some are more obviously on the nose for today's post, some are more swimming in the same general sea. I'm sure you can figure it out.

Yet even from this cursory glance, some things are obvious:

- In most Jewish cultures across the globe, there were unique and important religious/spiritual/healing functions that women (and, presumably, trans and gendernonconforming folks) played, and those roles were honored.

- Alongside the official religious sphere of canonized texts and rabbinic authority existed a vibrant set of oral traditions home and hearth and communal networks, run or at least generally dominated by women. This is true in most traditions, most certainly Jewish.

- While certain features of any of these Jewish spiritualities may resemble that of the local dominant society– Jewish cultures varied wildly for good reason– there are many ways in which Jewish women’s spirituality often retained some sort of common texture and common themes, common concerns with the evil eye, and demons, use of amulets. Etc.

A traditional Jewish women's song from Kerala, India in Malayalam: A "play song" performed at Hanukkah parties that covers biblical and midrashic stories about Sarah - her pregnancy, the birth of Isaac, and, naturally– Sarah's death by falling from a window when Satan told her that Isaac had been slaughtered.

(There's more music to come.)

And lastly, over to Hanne Blank Boyd– author of Fat, Straight: The Surprisingly Short History of Heterosexuality, and so much more.

She writes in her newsletter:

My paternal grandmother laid curses, and so did her mother. I imagine there were generations of curse-laying women prior, but I don’t know for sure. There tend to be.

My paternal grandmother and her mother were fairly typical eastern European kitchen witches, as I understand it, though I know my grandmother would have snorted with disdain at that label. Her approach was always that there was nothing at all out of the ordinary about what she did, and why on earth would you ask?

She wouldn’t say, my grandmother, but she would do things in front of me that she never did in front of my father or my brother. Once I watched her take the empty instant coffee jar full of salt down from the cupboard and fish around in it for a minute before extracting a little piece of paper. She unfolded it, grunted, lit it on fire with the firelighter she kept on the stove because the pilot lights could be unreliable, and dropped it in the sink, saying “that’s enough of that” under her breath. I asked what it was enough of and she said “It’s not going to happen again, so you don’t need to know.”Eventually I put two and two together: something bad happened and she wrote something about it down on a slip of paper, maybe the name of the person who did the bad thing, or the place, I don’t know. She put the paper in a jar of salt. The salt would, I supposed, corrode the paper, or weaken it, or dry it out, or something. At some point it would be sufficiently corroded or whatever, and she’d burn it to finish the job. The salt was not meant to preserve, but to destroy and more importantly, it seemed, to render inert whatever was put in it. Years later I would stumble across a reference to salt jars in some book on folklore and superstition and I was startled to discover that the whole business with the jar and the salt was not just a my-grandmother thing but an actual Thing thing, something that people who were not my grandmother did and had done for who knew how long...

Blank Boyd also talks about learning to read tea leaves from her grandmother, and about the curses that said grandmother laid

“on men in the neighborhood who had been cruel to women in their households.” (“I didn’t say he should die,” she mumbled under her breath. (He didn’t.))

That’s how it was, with my grandmother. It wasn’t a big deal. It was just a thing she did. A thing one did. Or at least might do. She kept her geraniums flourishing and blooming in the most profuse, spectacular fashion all summer long in much the same way, muttering to them when she watered them, telling them what was going to happen or else.

My grandmother never sat me down and said she was going to teach me anything. On the rare occasion that I asked her questions about her ways, I would receive only a ripe back-of-the-throat “Feh! I don’t know nothing.”

...I don’t have an empty Sanka jar full of salt and slips of paper because I don’t drink Sanka. There’s no reason it has to be a Sanka jar though....

If you asked me about any of it I’d say “Feh. I don’t know nothing.” But if I were in the right mood, I might still offer to read your leaves.

🌱❤️🪬❤️🌱

Like this? Get more of it every week.

For FREE or MORE. To your inbox or access directly on the website:

A note on the subscription model:

I want my work to be as accessible to as many people as possible, in as many ways as possible. That's why the Monday essays are free, and why we donate subscriptions to anyone for whom paying is a barrier to the House of Study posts.

I also believe people should be paid fairly for their work. Needless to say, these two values sometimes seem to be in conflict, but I do what I can to find a fair balance. I offer many resources for free, and charge for others. When you donate generously or pay at the top of our scale, that helps support the work I do, provides access for those who have fewer resources, pays for the infrastructure and the technical and practical support that it takes to do this, and helps us keep the work sustainable.

And as always, if you want in to the Thursday space but paying isn't for you now, just email support@lifeisasacredtext.com and we'll hook you up.

And if you’d like to underwrite one of these donated subscriptions, you can do so by signing up at one of the higher subscription points.

And if it resonated with you, please share this post.

Sending a big pile of blessings and goodness your way. 💕

And because I want to lift up as many voices (literally) as possible:

To my consternation, the person writing the liner notes only wrote about the music and didn't tell me anything about the context of this song. Bukharian Jews are an ancient community from Central Asia.

The Abayudaya–Luganda for People of Judah– are a Jewish community in eastern Uganda. I had the great joy of attending rabbinical school with their rabbi, Gershom Sizomu, who is an absolute peach. This is a women’s setting to a traditional Psalm.

From the village of Giv'at Ye'arim, Yemen. For a ceremony at the end of a long evening of singing and dancing; the performer accompanies herself on an oil can, sometimes with other women in the community.

The Jews of Habban (in South Yemen) are both ancient and have a distinct culture; this is a women's song about marriage sung by two groups who sing accompanied by a sahn (a copper tray, if I understand) and hand-clapping.

Tora ta pulia “When the wedding ceremony is finished.” A wedding song in Greek, Ioanina tradition, sung by Anna Raphael. The Romaniote Jews in Ioanina– one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world– have a whole suite of wedding songs in Greek. (Anna Raphael also knew the very ancient tradition of funeral lamentations.)

Rabbi Noam Lerman has done some incredible work on Tekhines--supplications that were regularly written and prayed by, and centered the experiences of women, trans, and gender non-conforming people, including setting them to new melodies. Here are two from this project:

EVEN MORE:

A Millennium of Jewish Women's Voices, Mapped, by the Jewish Language Project. Pretty cool. Includes some stuff by men about women, but largely an extraordinary resource of music, letters and more by Jewish women across languages and cultures

Rabbi Noam Lerman's

Join me for a new class, “Yiddish Gothic: Three Stories by Sarah Hamer-Jacklyn,” August 6, 13, and 20th at 7:00 pm (EST).

— Rokhl (@rokhl.bsky.social) 2025-07-27T05:31:53.514Z

Please SUBSCRIBE and SPREAD THE WORD about Life is a Sacred Text!

Without the built-in networks of the Nazi-enabling Substack, we over here trying to stay on the nonprofit model (this runs on Ghost) are at a distinct disadvantage. We can only survive and flourish with the help of supportive readers! ❤️🌱 THANK YOU!